The Grand Mound Historic Site on the Minnesota-Ontario border west of International Falls will remain closed to visitors, the Minnesota Historical Society has announced. Located at the confluence of the Big Fork River and Rainy River, it is part of what’s considered one of the most significant such sites in the Midwest.

MNHS acquired the site in 1970 and opened it to visitors from 1976 until 2002, when it was closed due to budget cuts. Its future has been uncertain ever since.

After four years of discussion with local citizens, education and cultural experts, and with input from 18 Native American communities, MNHS decided to keep the site closed to protect its sanctity. Native Americans will continue to have limited access to the site.

“This site is first and foremost a burial ground with thousands of human remains still interred there,” said Joe Horse Capture, director of Native American Initiatives at MNHS. “This decision honors Native ancestors and ensures respect for Native American culture and history.”

The organization will continue working on a long-term plan for the site, which may involve transferring it a Native American tribe or tribes.

Thousands of years of history

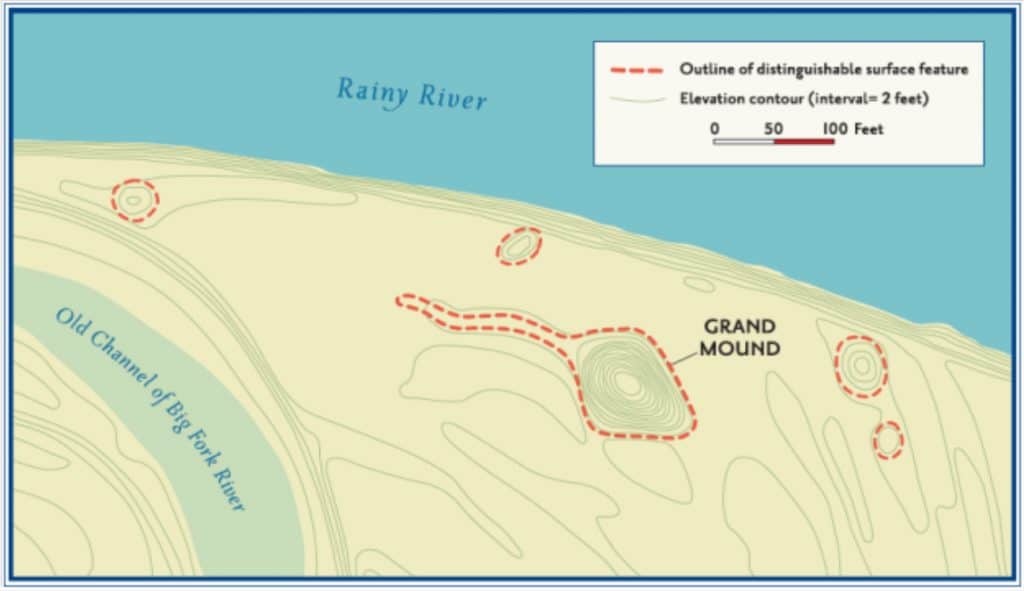

There are five mounds found at the site, which is part of a network of more than 20 burial mounds on the Rainy River between Lake of the Woods and Rainy Lake.

The Grand Mound site was first occupied by humans about 5,000 years ago, with the large and elaborate burial mounds built by the Laurel Native Americans some 2,000 years ago. It was home to villages and sturgeon fishing camps, where people gathered in the spring to harvest spawning fish.

The area today is the homeland of the Ojibwe people, who first arrived in the area about 500 years ago, after the mounds were built. It’s not known what modern Native American people are descended from the Laurel Culture, but they may have been Algonquian-speaking groups include the Cree, Blackfeet, and A’aninin (Gros Ventre), which are today located northwest of the area. Dakota tradition indicates the tribe may have had some contact with the site.

Grand Mound mystery

The largest mound, called Grand Mound, is 25 feet in height and 100 by 140 feet wide, containing nearly 5,000 tons of earth, making it the largest Native American earthwork in Minnesota and the largest surviving “prehistoric” structure in the Upper Midwest.

Grand Mound is diamond-shaped with what appears to be a tail. It was interpreted as a serpent by archaeologists in 1995, but recent research indicates it may be a muskrat. In a 2015 article in Minnesota History magazine, MNHS National Register archaeologist David Mather argues that, perhaps surprisingly, a muskrat may make the most sense.

Muskrats are perhaps “grand” when compared to most other rodents, but they are nonetheless small animals and it may be surprising to think of them as the inspiration for a giant effigy mound. This model proposes, however, that the Grand Mound effigy was not meant to be the small animal itself but, rather, was built to represent a big idea.

In world-creation (or re-creation) stories from many parts of the world, the Earth Diver plays a heroic role in the aftermath of a global flood. In these stories, some mud must be retrieved from deep under the water so that dry land can be magically created. Always a diminutive creature such as an insect or diving duck, the Earth Diver succeeds when stronger animals have failed and hope is fading. Oral traditions of a muskrat as the Earth Diver are known from Algonquian-speaking groups including the Ojibwe and Cree, as well as Siouan speakers including the Dakota.

Several non-native archaeologists performed excavations and removal of remains and sacred objects between 1883 and 1956. Remains that had been removed and deposited at the University of Minnesota were released back to their descendants at a ceremony in 1991.

References

- Sacred Burial Ground to Remain Closed with Limited Access for Native Americans – MN Historical Society

- The Grand Mound Historic Site Recommendation Report: Access, 2018 (PDF) – MN Historical Society

- Grand Mound and the Muskrat: A Model of Ancient Cosmology on the Rainy River (PDF) – David Mather, Minnesota History, 2015