On February 13, more than 40,000 students visited the vast, island-studded lakes of Voyageurs National Park. Thanks to innovative online programming, kids from across the United States beamed onto the ice-covered lakes near the Canadian border. They learned about snowshoes, ice-fishing, the Ojibwe people, the French-Canadian voyageurs, and the importance of dark night skies.

Boreal Stargazing Week also included in-person events at the park and the Twin Cities area. It’s all part of a growing education program at Minnesota’s only National Park.

In the past several years, Voyageurs Conservancy and the National Park Service have built out a series of programs that educates young people about the park from kindergarten to college. The virtual park visit in February was part of Voyageurs Classroom, which received a nearly $1 million grant last year from Minnesota’s lottery proceeds. The funding will make it possible to hire more staff and expand educational efforts.

”Voyageurs is this hidden gem,” says Breanna Trygg, education and outreach director at Voyageurs Conservancy. “We want to make sure that Minnesotans are aware of what we have here and feel like it’s a place that’s a classroom for students and a place to go recreate.”

Trygg was hired in 2021, and has a lifelong connection to Voyageurs. Her family had a cabin in the park since before it was established as a National Park in 1975, until 2009. Her great-uncle was Noble Trygg, a forester who was involved in the creation of the National Park. Trygg spent summers exploring the woods and waters — and now shares it with the next generation.

Three years ago, after Trygg had been living out-of-state for 20 years, she and her family decided to move back to Minnesota. That same week, the education job at Voyageurs Conservancy was posted.

Voyageurs fortunately had an excellent foundation of educational resources at that point, but the National Park Service had recently lost funding for a staff educator. Trygg’s was hired was to fill that gap, rebuild the previous programs, and create educational opportunities that would cover all stages of education.

Live from a frozen lake

The Feb. 13 virtual event, which featured park rangers and other personalities sharing the wonders of winter, was part of a partnership that Voyageurs has developed with Expeditions in Education and several other organizations. The emphasis is on the park’s famously dark night skies, which have earned it international recognition in recent years.

A century ago, before the widespread use of outdoor electric lighting, almost all humans could see the stars at night. Today, about one percent of people live without light pollution. Voyageurs is a rare place where there is little outdoor lighting for a long ways. The stars and the aurora borealis can be brilliant.

There were activities and programs throughout Boreal Stargazing Week, including in-person events at the National Park. Teachers anywhere could also sign up to have three live lessons streamed directly to their classrooms from the National Park, with supporting materials for learning before and after the event. Several large school districts across the country chose to stream the main event to every class in their elementary and middle schools, quickly expanding the audience.

There were students watching who had never seen snow, while people walking on frozen water.

“It was one degree at noon when we were live-streaming,” Trygg says. “The kids were astounded we were standing on three feet of ice.”

The event showed off the intense winter weather, northern Minnesota’s wild lakes and forests, and the incredible nighttime sights.

“[I’m] pretty sure this was the best thing our school has ever participated in,” one teacher participant later wrote. “Seeing snow for the first time made some kids cry. Thank you for being so funny and informative.”

Expansive education

Voyageurs Classroom has several other ways of reaching students, as the organization seeks to develop programming to connect with young people wherever they might be in the country or in their school career. The organizers want students to see the park as their classroom, as well as a wonderful place to enjoy nature.

For children at local schools in Koochiching and St. Louis Counties, there are opportunities for field trips. They might take a boat tour, explore a historic site, and learn about the complex ecosystem. But for kids elsewhere in Minnesota, and beyond, there are ways to begin building a connection to the park without the long drive.

”We know we can’t bring every student all the way up to Voyageurs,” Trygg says. “But there’s something magical about Minnesota’s only National Park.”

In the past three years, the education effort has expanded to include several ways for young people to experience Voyageurs National Park, and feel a sense of stewardship. It includes everything from virtual classroom visits by Voyageurs educators to internships for college students, and even continuing education experiences for teachers. Funding for the project was provided by the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR).

Instruction in Voyageurs’ programs covers numerous topics, seeking to balance historic and scientific themes, and closely connecting to state curriculum standards. Students might study how beavers are adapted to the environment or why the Ojibwe people came to live here. Because the dark skies are an important part of the park, an engineering activity includes designing a light fixture to reduce light pollution.

Park on the go

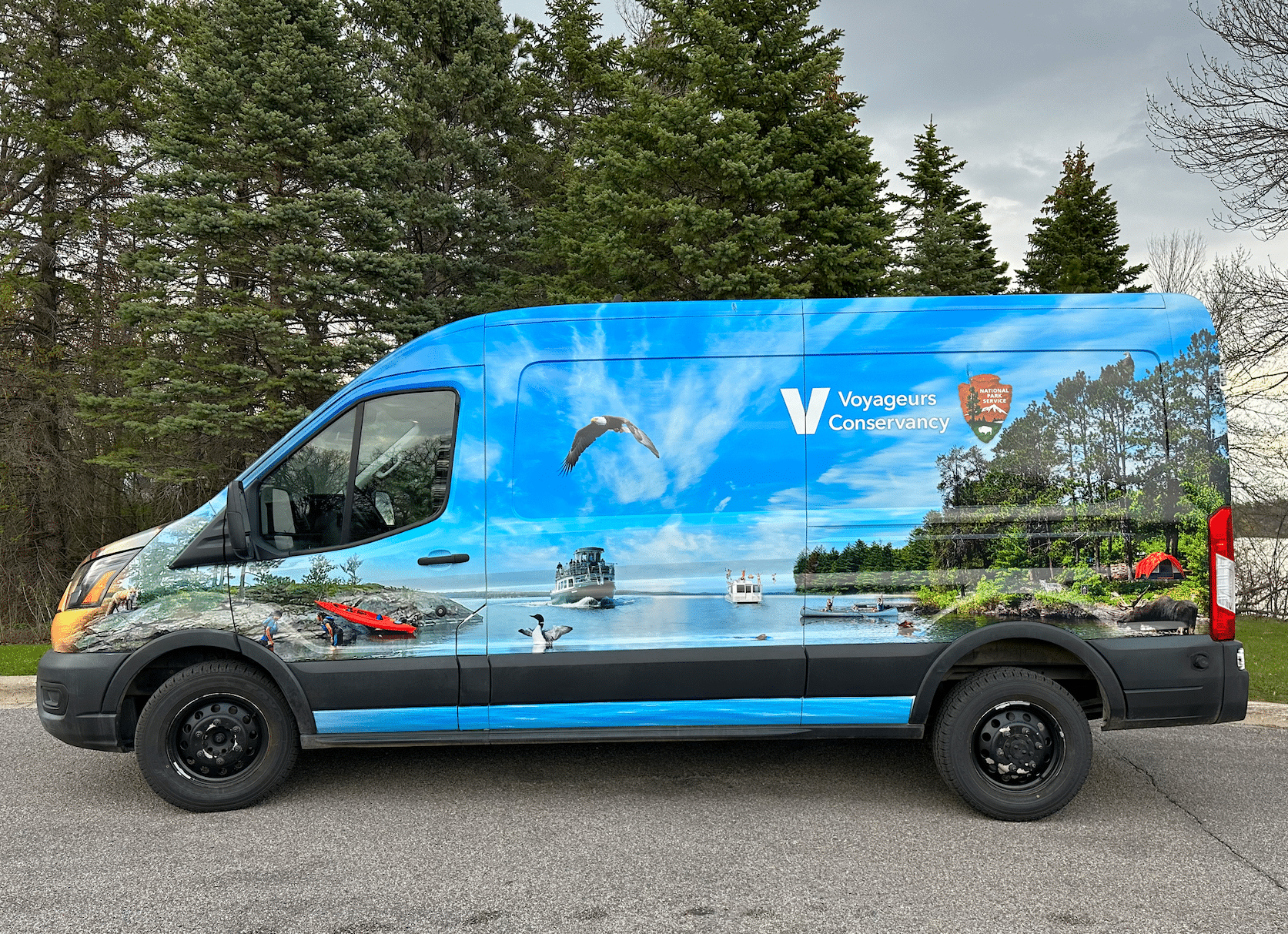

One of the final pieces of the program is nearly in place: the mobile classroom. This specially outfitted van carries curriculum materials and snowshoes, binoculars, and other gear for outdoor exploration and education. The mobile classroom is being carefully developed, based on deep understanding of “what works best for teachers, for us, and for students,” Trygg says.

Creation of the mobile classroom has been led by Moss Schumacher, a graduate student in environmental education at the University of Minnesota – Duluth. Schumacher has used their education in psychology and cognitive science to develop the vehicle and its curriculum. The mobile classroom will launch this fall, with Schumacher as educator and coordinator.

“The world is changing. The land is changing pretty quickly,” Schumacher told UMD News. “Being able to build a relationship with the place where one lives I think is enormously helpful. As we move through these countless changes, being able to stay grounded in nature and the place that exists where you are is a way to stay connected as people. I want to give that to kids.”

When the Mobile Classroom hits the road, some of Voyageurs National Park will come to students, rather than the other way around.

Teaching teens

Interaction to Voyageurs via video screen or a van visit in primary school can get a student excited about science, want to seek out nature, instill a connection to the history of what’s now called Minnesota. It can change lives, and set kids on a course for conservation careers.

The world needs diverse professionals to do these jobs, but there are a lot of obstacles to getting a foothold in the field. That’s why for middle and high school students, Voyageurs has developed advanced programs that builds skills and knowledge students will need if they wish to consider studying a relevant field after high school.

“It offers great career exposure and talking about natural resource careers, but also the skills of camping and canoeing,” Trygg says.

Through the Teen Ambassadors program, which is operated in partnership with Wilderness Inquiry, teenagers visit the park for kayaking, camping, learning, and service work. They also get guidance from current professionals about natural resources education and employment.

This year, the Teen Ambassador program is transitioning to be led by Indigenous people. Its foundation of partnership and protection will continue, while participants will be primarily young Native people, whose homelands include Voyageurs.

The Ojibwe are an essential part of the park today and its history. The Ojibwe, or Anishinaabe, people lived in what’s now Voyageurs National Park for centuries before any white fur traders, settlers, loggers, miners, or tourists. The Bois Forte Band’s has reservation land near Voyageurs, and signed a treaty with the United States government in 1854 that its timber and other resources, while the Native people retained rights across the region.

The decision to support the program under Indigenous leadership is part of a broader effort underway at Voyageurs Conservancy to inform appropriate cultural representation. This winter, the staff hosted four meetings around the Bois Forte Reservation to simply listen to Indigenous ideas and knowledge. They have also met with the tribal council multiple times, and reviewed all their curriculum materials concerning the Ojibwe.

“A big part of next year will be integrating all that we’ve learned deeply into our curriculum,” Trygg says.

Field fellowship

Walking around the wilderness all day, studying its wildlife, protecting the environment, helping people experience a park, are dream jobs for some people. It is also complicated work, as natural resource employment needs a mastery of both backcountry skills and scientific techniques. Voyageurs field fellows have a unique chance to gain these requisite experiences.

“Field fellows are the natural endpoint of our environmental education,” Trygg says.

For college students and recent college graduates, this program places young people with the National Park Service, Voyageurs Wolf Project, while the nonprofit provides a financial stipend, housing, and transportation while they’re working at Voyageurs.

The field fellows are encouraged to follow their passion in completing a capstone project during their fellowship. Projects so far have included everything from a complex interactive map about wolf research, and another who created an oil painting of a collared wolf.

While they work directly with National Park Service staff and other professionals, field fellows also belong to a cohort of other fellows. Throughout their time at Voyageurs together, they have opportunities for mentoring, accountability partners, and professional development. It provides critical support as they transition from education to employment.

Call of the wild

One night last August, some 250 people came to an event in Voyageurs National Park to see the stars. Among them was Voyageurs educator Jesse Gates, who has appeared remotely via video screen in classrooms all over the country, teaching about Minnesota’s only National Park.

The parents of a young girl urged her to talk to Gates, who had virtually visited her classroom months before. After the visit, the girl had launched a campaign in her family to visit Voyageurs for their first time. Now, she saw the smiling face of Gates, who had first gotten her excited about the dark skies and wild waters of the 218,000-acre park. She was a little in awe, like meeting a celebrity — and setting foot in a legendary land.

From the first virtual visit to this very real experience, it’s easy to imagine that child going on to become a National Park ranger, a scientist, or an astronomer. The sky is the limit.

As this kind of experience is repeated by kids from all over the United States, the value of Voyageurs National Park is being passed down to its youngest owners — and future stewards.