From tiny insects to global changes, several forces are making life more difficult for some types of birds in northern Minnesota’s forests. The most recent survey of birds across northeastern Minnesota’s National Forests show continued declines for some iconic species.

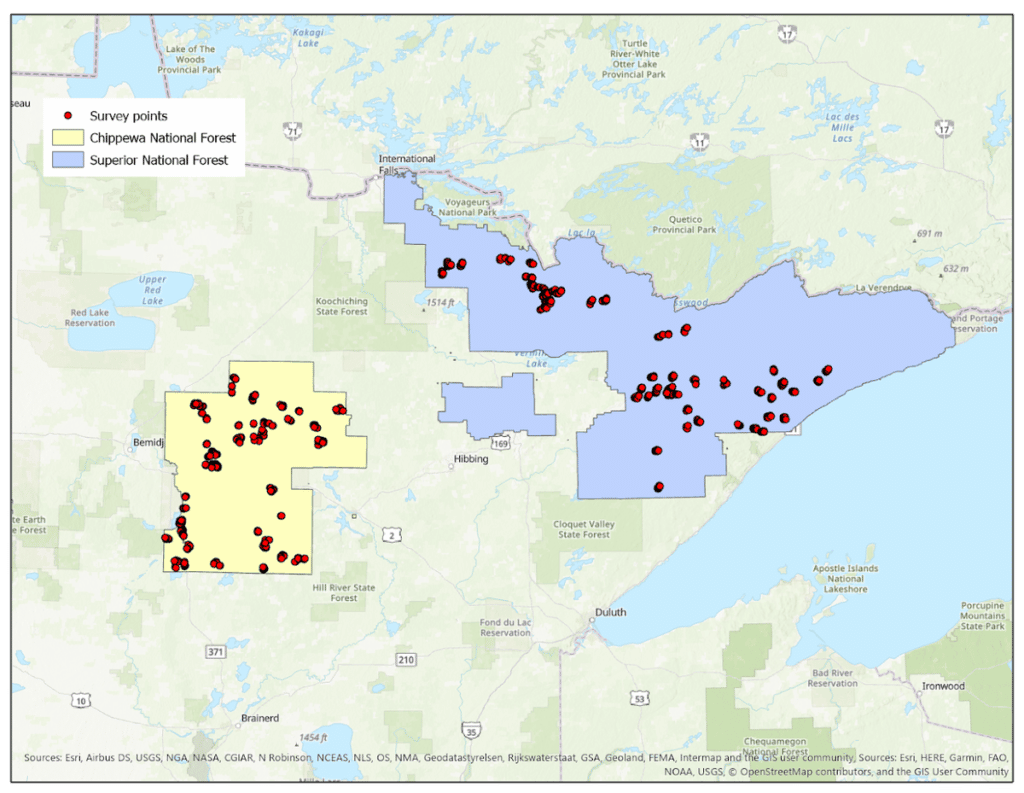

The University of Minnesota’s Natural Resources Research Institute has been involved with annual bird surveys of the Chippewa and Superior National Forests for nearly 30 years. Scientists visit 1,000 different points and watch and listen for 10 minutes at each point, recording every species they observe.

Researcher Steve Kolbe, an NRRI avian ecologist, said the long-term project has allowed scientists to see that the situation is dire for some species. For example, the Connecticut Warbler has experienced what Kolbe called an “alarming” decline in northern Minnesota.

From dozens to none

“When we started the surveys in the mid 90s, we’d get somewhere on the order of 30 to 40 individuals over the course of the one thousand points that we go and survey every year,” Kolbe told WTIP’s Outdoor News podcast. “And then the last three years, we’ve had zero.”

Kolbe said the bird seems to have been essentially extirpated from the Superior National Forest, meaning it is locally extinct.

Like most changes in bird populations, Kolbe said there is no one reason for the Connecticut Warbler’s decline. But a big one is a loss of suitable habitat. The bird only nests in swamps with conifers like tamarack and black spruce. But the eastern larch beetle, a native insect that’s population has exploded in recent years due to climate change, is decimating the region’s tamarack trees. Meanwhile, black spruce is being harvested by loggers in higher numbers than the past. Kolbe also said as a long-distant migrant, Connecticut Warblers face habitat loss and other dangers along a broad area stretching from Canada to Brazil.

To address habitat issues, the NRRI has been working on experimental projects on the Red Lake Wildlife Management Area in north-central Minnesota. Scientists are monitoring wildlife populations as the Department of Natural Resources tries logging techniques that leave habitat behind.

Familiar feathered friend

Another species the scientists found in decline is familiar to people who camped in the Boundary Waters: The Canada Jay, aka Gray Jay, Whiskey Jay, or camp robbers. The bold birds are known to be curious about people and not shy, and to even grab food from campsites or human hands. The Timberjay newspaper reports that citizen scientists in the heart of the Superior National Forest found few Gray Jays during an annual count in December, hitting a 40-year low.

“The Isabella count had previously set the North American record for the most Canada jays on a count, with 154,” the Timberjay reported. “This year, however, counters in Isabella found just 19.”

The problem is probably related to climate change. Canada Jays have a unique strategy for surviving winter and raising young. They cache food all fall around their territory, in tiny packets the size of a pea, stuck with their saliva to tree branches. This food not only helps the birds get through winter, but provides food for chicks, which Canada Jays have relatively early in the spring. The method works well, as long as it stays cold enough.

But average autumn temperatures in northern Minnesota are rising quickly, and researchers have determined that weather that’s too warm can spoil the food caches. Birds have less food to feed their chicks, and the population shrinks.

Canaries in the ecosystem

“Our results demonstrate that fall environmental variables, most notably the number of freeze–thaw events, carried over to influence late-winter fecundity, which, in turn, was the main vital rate driving population growth,” scientists from Ontario’s University of Guelph found. “These results are consistent with the hypothesis that warmer and more variable fall conditions accelerate the degradation of perishable stored food that is relied upon for successful reproduction.”

The Timberjay also noted that, as Canada Jay numbers have fallen, the number of their cousin, the blue jay, has risen. Some observers think the blue jays may also effectively steal Canada Jay food caches, contributing to the problem.

NRRI scientist Kolbe says, while the bird declines are concerning, what they say about the environmental health of the region is a bigger problem. Referring to “canaries in the coal mine,” he said bird populations can point to issues like loss of insects or trees.

“Their populations show the problems that may be happening in the ecosystem,” Kolbe told WTIP.

While several species have seen declines over recent decades, other species are thriving. Logging, climate change, and other human activities can create habitat more amenable to some birds. Golden‐crowned Kinglets and Black‐and‐white Warbler stood out this year for a rising population. Two kinds of birds listed by the state of Minnesota as species of greatest conservation need, Cape May Warblers and Purple Finches, are also on the rise.

More information:

- Connecticut Warbler and other songbird populations on the decline in Superior National Forest – WTIP Outdoor News

- Canada jays may be a victim of a warming climate – The Timberjay

- Minnesota National Forest Breeding Bird Monitoring Program, Annual Report, 1995–2022 (PDF) – U of MN, NRRI

- Sutton, AO, Strickland, D, Freeman, NE, Norris, DR. Climate-driven carry-over effects negatively influence population growth rate in a food-caching boreal passerine. Glob Change Biol. 2021; 27: 983– 992. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15445