A new independent film supported by National Geographic digs into the debate over wolves on Isle Royale National Park in Lake Superior. The filmmakers show how the wolf population plummeted in recent decades—partly due to climate change—and how the exploding moose population threatened to permanently damage the island ecosystem.

‘Wolves of Isle Royale: The Quest for Survival’ was made by Slade Kemmet, a National Geographic Explorer, filmmaker, and photographer based in Minnesota, with funding from National Geographic.

“The wolves on this often-forgotten island tell a much larger story,” the filmmakers say. “Their plight foreshadows the future of countless species across the globe, as the effects of climate change intensify. This is not simply the story of wolves, this is the story of our future.”

The film makes several comparisons between the Isle Royale wolf reintroduction and Yellowstone National Park, where wolves were also reintroduced in the 1990s in response to ecological changes caused by their absence.

It includes interviews with five individuals with unique experience and insights on the projects: Phyllis Green, retired Isle Royale superintendent who led the reintroduction effort; Doug Smith, a National Park Service wildlife biologist who worked on the Yellowstone reintroduction and as an adviser for the Isle Royale project; John Vucetich of Michigan Tech University, co-director of the Isle Royale Wolf-Moose Project; Jay Austin, a professor who works at the University of Minnesota’s Large Lakes Observatory in Duluth; and Kevin Proescholdt, the Minesota-based Conservation Director at nonprofit Wilderness Watch, and longtime wilderness advocate.

Warmer winters

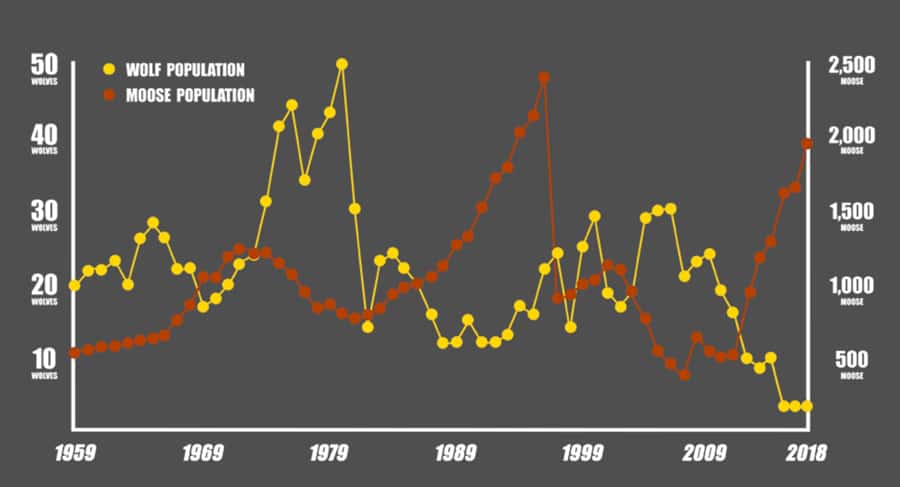

In the film, scientists explained how wolves were disappearing from Isle Royale in part as a result of climate change. The population decline was linked to inbreeding, which is usually alleviated by occasional arrivals of wolves from the mainland over ice bridges in winter.

But Jay Austin explains how warming winters have resulted in fewer ice bridges in the past two decades. “Prior to 1998, more often than not there was substantial ice on the lake,” he says. “And after 1998, more often than not, there was very little ice.”

The frequency of adequate ice cover on Superior for wolves to cross has gone from three out of four winters in the 1960s, to one out of 10 winters today, according to Austin.

With far fewer opportunities for new wolves to come to the island and breed, infusing diversity in the gene pool, the wolves nearly disappeared. That led to the moose population exploding, which was beginning to affect the health of the forest due to over-browsing.

“Climate change is this hurricane and we’ve got this candle up and we’re trying to keep that candle burning,” Smith says, explaining what he sees as the critical role of protecting healthy ecosystems.

Wilderness or wolves

While many people believed that meant a wolf reintroduction was necessary, others say Isle Royale is protected by the Wilderness Act, which should prevent undue human meddling. Ninety-nine percent of the park is designated wilderness.

“The appropriate role for the wolf project on Isle Royale is to let the wolves decide,” said Proescholdt, of Wilderness Watch. “We believe [reintroduction] flies in the face of the humility and restraint the wilderness act requires.”

Proescholdt also says the reintroduction effort sets a precedent for the National Park Service to “manipulate the wildness out of wilderness.”

The National Park Service’s Smith disagrees. The biologist worked with wolves on Isle Royale for 15 years before heading to Yellowstone. His role in that reintroduction led to serving as an advisor on the Isle Royale reintroduction project.

“Nature is on the run and we did that. Wolves are on the run, so where can we have them now? Where’s a good place for them?” Smith says. “Yellowstone is one of the best places in the continental United States for wolves, so is Isle Royale.”

Population restarted

Despite the ongoing debate, the National Park Service and researchers did move ahead with reintroduction beginning in 2018. The National Park superintendent at the time, Phyllis Green, explained that they felt a sense of urgency to intervene before damage caused by moose was irreversible.

Nineteen wolves have been relocated to Isle Royale since then, with 14-16 believed to still be alive. Two pups were born in the spring of 2020. This is probably the last chance for the island’s wolves.

“We’ve agreed to restart that population,” she says. “Once we restart it, we’re not going to step in again.”

The scientists believe it could take up to a decade to see the wolves have an impact on the moose population and the overall ecosystem health.

The first wolves to colonize Isle Royale arrived over an ice bridge in 1948, about half a century after moose are believed to have arrived by swimming across Lake Superior. The National Park was created in 1940, and designated as wilderness in 1976. In 1958, the wolf-moose study began, continuing today as the longest running study of predator and prey relationships in the world.

In addition to the 13-minute film, the filmmakers also provided extended interview videos with all five subjects: Phyllis Green, Doug Smith, John Vucetich, Jay Austin, and Kevin Proescholdt.

More information:

- Wolves of Isle Royale: Quest for Survival – Film website

- Isle Royale Wolves – National Park Service

- Wolves and Moose of Isle Royale – Study