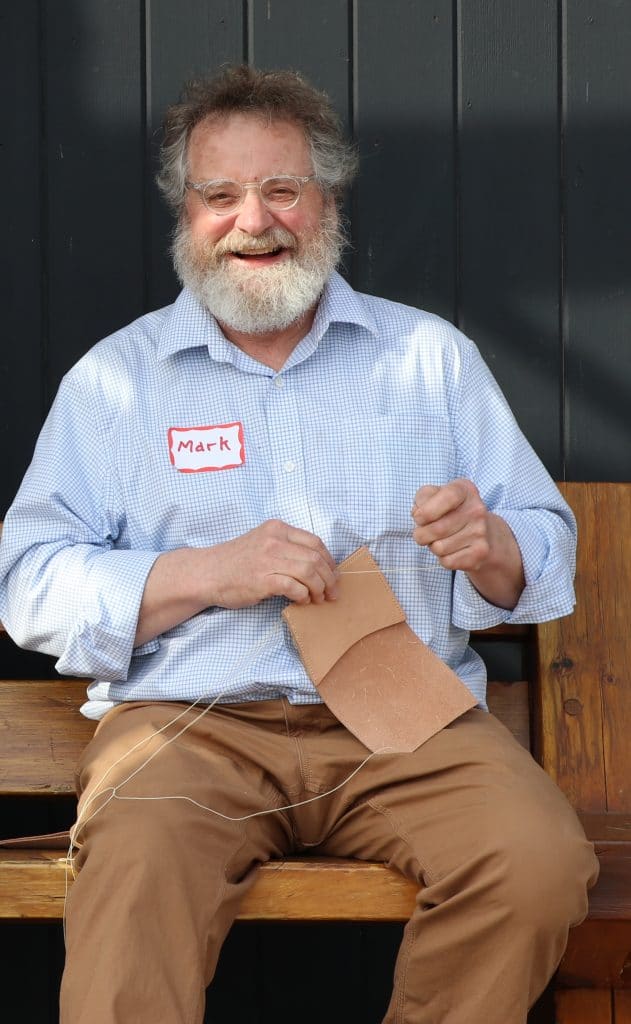

In Grand Marais, Minnesota, a gateway to the Gunflint Trail and canoe country, there is a place where the traditional crafts of the north are celebrated. From timber framing and boat building, to basketry and knitting, craftsmen and women gather to share their knowledge and skills—often using traditional resources like birch bark. It grew out of a single class, when Grand Marais resident Mark Hansen taught 14 students to make Inuit skin-on-frame kayaks in a Coast Guard boathouse. That led to the first catalog, which offered 23 courses before classrooms were secured. But as the saying goes, some things are meant to be. The city had acquired Forest Service buildings on the shore of Lake Superior, and North House Folk School was born.

Now, 20 years later, to say the school has grown risks overlooking what it has truly become: a thriving community. For while its size and impact have increased under the leadership of executive director, Greg Wright, it’s about more than numbers of classes or its economic contribution to the community (although, estimated at $6 million per year 10 years ago, the latter is impressive). It’s about the people who have learned to create things with their hands that they could otherwise buy—school children and at risk youth, and adults craving a sense of fulfillment they don’t find sitting in front of a computer.

Just this summer, Wright says that during the annual Wooden Boat Show, 1,000 people gathered for the summer solstice pageant. The following day, 50 instructors got together for morning coffee. About 150 people attended the school’s annual meeting, and 75 gathered on shore to witness the launching of a birch bark canoe built in honor of the school’s 20th anniversary. It’s a far cry from the dozen or so instructors who gathered for coffee during the first Wooden Boat Show. Add international connections, and the school’s reach is growing more impressive. In May, Norwegian craftsmen stopping by for half a day stayed for three, and news of their visit drew many locals to campus.

“Our story is reaching out and connecting to the world and gathering people together,” Wright said. He’s been at the school’s helm for 16 years, and during that time, earned a reputation for having a smile on his face and a hug or handshake for everyone he greets.

“You know he’s had too much coffee when he runs across campus with a smile on his face,” Hansen said. He lobbied hard to hire Wright. At the time, he had been sharing the responsibilities of director with another instructor, and as the school’s popularity grew, he knew the school needed someone with a head for numbers and an analytical mind. In Wright, he saw someone perfect for the job. “He gets it. He gets the whole concept of the folk school tradition.”

For Wright, the job was a perfect fit.

“Paddling through northern landscapes was a mainstay of my life, a core of the fabric of my experience and something that I really valued. So part of what drew me here and kept me here is that I get to be of here. I get to call this place home.”

He certainly seems to epitomize the school’s traditions. Wright and his wife built their own timber-frame sauna and, as he said, had so much fun they built their own timber-frame house. They’re organic gardeners and beekeepers, and have built their own toboggan. Together with their daughter, they restored a Seliga wood-canvas canoe and now paddle it through the wilderness.

While Wright is clearly a craftsman, he calls the running of the school his true craft. “Craft has been part of the story of my life, part of why I love being here. And so, do I get to build as many boats as I wish I did? No, but of course not. My main craft is building a folk school, and I feel lucky to have that as my craft.”

He does not, however, take credit for the ways the school has grown. He credits instead the dedicated instructors and the students who embark on what Wright calls a sort of pilgrimage to attend courses on the North Shore. “When you start to get to know a landscape or when you begin to use your hands, you’re digging into the guts of what it is to be human. You’re experiencing something that has been with us over the eons, this idea of being part of the landscape and using your hands to engage it.”

There is something different, he suggested, about building a paddle in the city versus building one at North House Folk School, where you can walk to the cobblestone beach, step into Lake Superior and wet the blade. The northern landscape is intrinsic to the school.

“We are not trying to retreat to the past. We are trying to connect the past, the present and the future together to make sure life stories are rich and so is our perspective on what makes us human. So we think of life as something more than what Amazon allows us to purchase,” he said.

Mark Hansen would likely agree. He says the spirit of the school reaches back to Scandinavia, where folk schools grew out of the thinking of Danish pastor Nikolaj Grundtvig, who was born in the 1780s and argued for land and education reform. According to Hansen, the schools inspired by his way of thinking were characterized by a lack of competition. Hansen was particularly taken by Grundtvig’s idea that in order for a person to know who he is, he has to understand where he comes from.

That is in many ways what North House Folk School provides for its students by focusing on crafts of the north: a way to see themselves differently—apart from their jobs, their salaries and other common measures of success.

“It has given people permission to be themselves…” Hansen said. “And when they can be themselves, they find out they have a story to tell. They have something to offer. It emboldens people to say who they are.”

That is perhaps why, in setting out to create the next generation of artisans, the school has also helped foster the next generation of the Grand Marais and North Shore communities. Grand Marais mayor Jay Arrowsmith-DeCoux was a North House intern, as was Amy Demmer, executive director of the Grand Marais Art Colony. A social services employee teaches how to turn wooden bowls, and another supplements his livelihood as an organic farmer through his work at North House.

It’s an impact that Hansen and Wright couldn’t have predicted, but certainly speaks to the school’s lasting influence. As Wright said, “This isn’t something we planned and yet our mission is to enrich lives and build community through the teaching of craft… It’s a joyous affirmation of our efforts that one of the unanticipated outcomes is that some people stay not just involved, but geographically connected.”

Get involved with North House Folk School at https://northhouse.org.