New reports from the University of Minnesota document whether there is enough habitat for elk to survive in three areas around Duluth, MN, and whether citizens in the area would like the animals reintroduced.

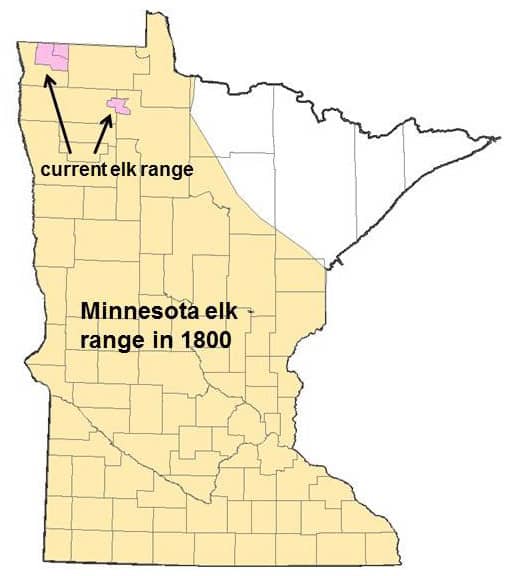

The studies are part of a lengthy process to determine whether or not the large ungulates could be restored to additional parts of their historic range. While the animals once ranged over most of Minnesota, today there are only two small wild herds in the far northwestern corner of the state.

“Re‐establishing this keystone herbivore will help restore the state’s traditional wildlife heritage, diversify the large mammal community, increase tourism from wildlife viewers, and eventually provide additional hunting opportunities,” the researchers write.

Elk were eliminated from the state in the early 20th century by overhunting and habitat loss. Besides northwestern Minnesota, the animals have successfully been reintroduced to Wisconsin’s Clam Lake region, as well as several other eastern states including Virginia, Kentucky, and Arkansas.

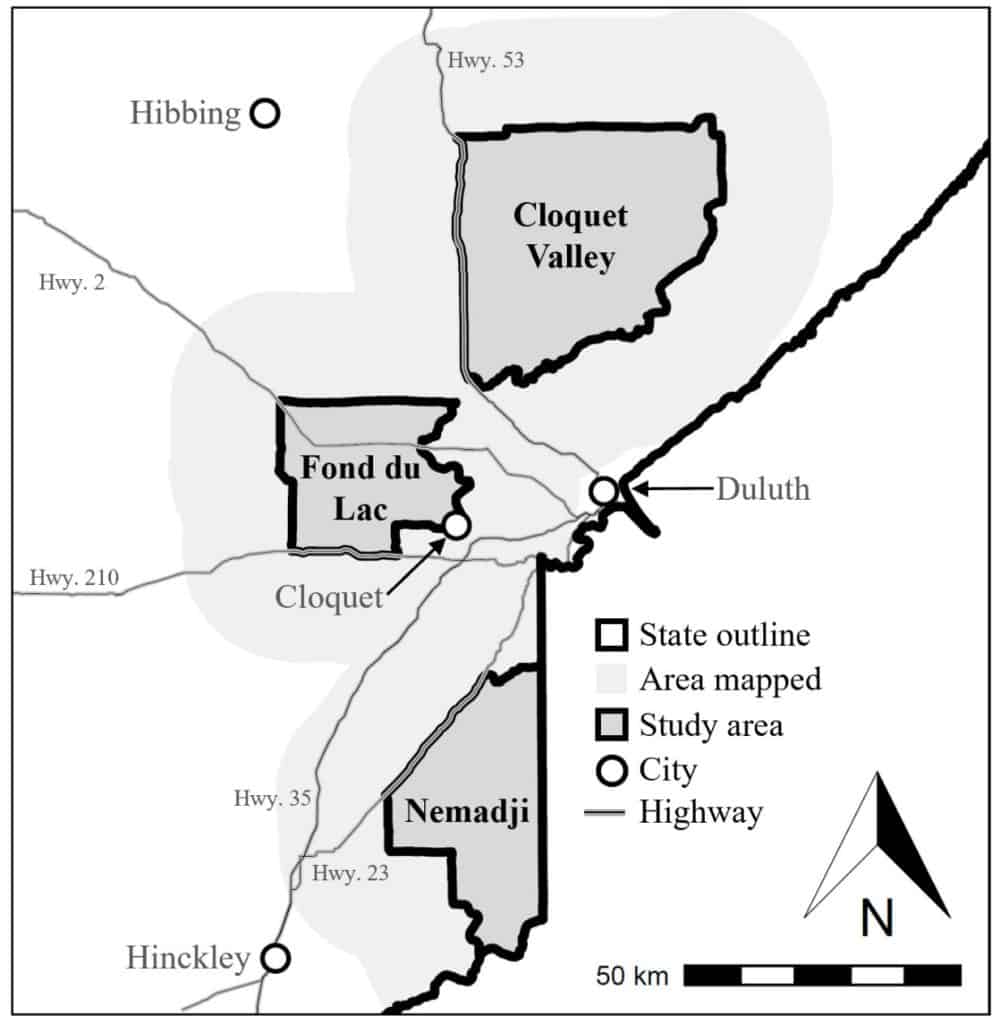

Biologists looked at the Cloquet Valley State Forest north of Duluth, the Fond du Lac Ojibwe Reservation to the west of the city, and the Nemadji State Forest to its south.

They say experiences in other states show that there must be food, habitat, and public support for elk reintroduction to succeed.

Local support

Opinion surveys conducted throughout the region found that about 80 percent of people who live and own land there would support local reintroduction.

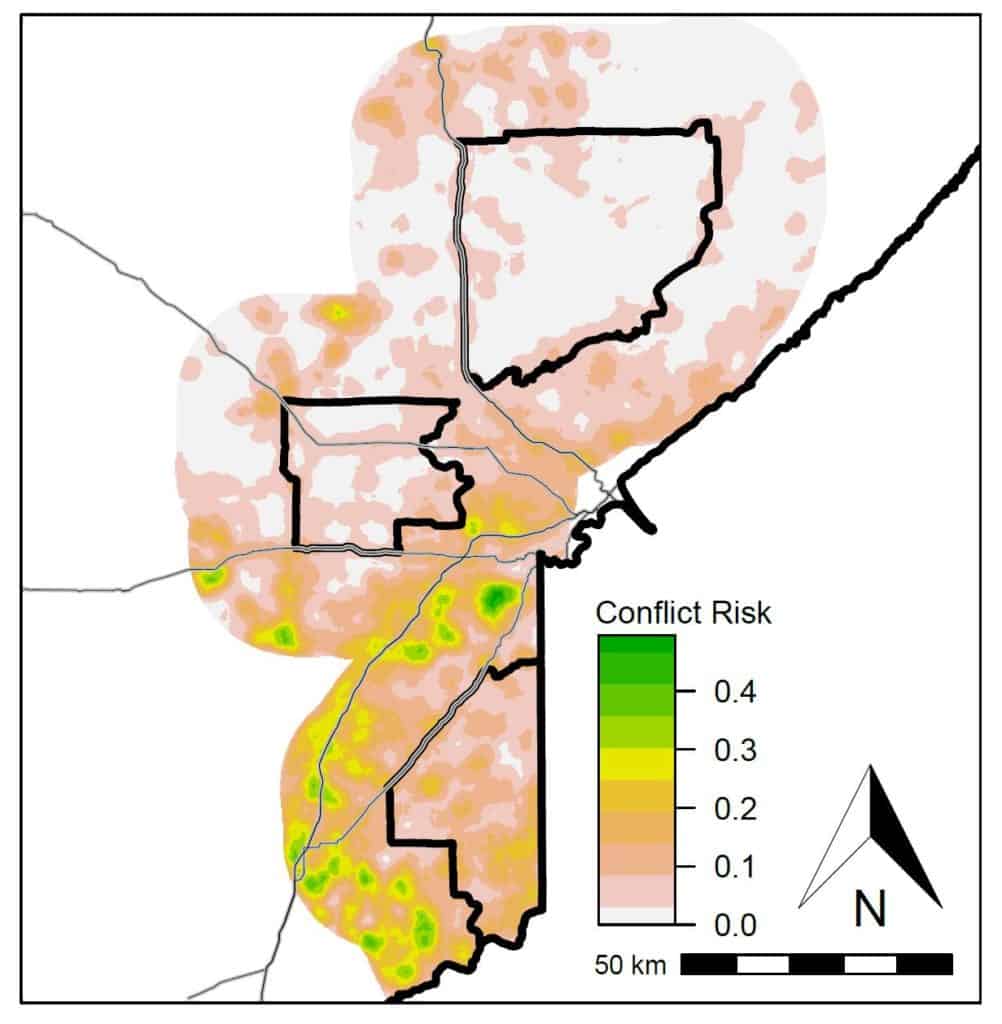

“Landowners and local residents perceived that there would potentially be moderate risk from restoring elk within the study areas,” researchers reported. “Overall, landowners and local residents perceived that elk would pose the greatest threat to the health/safety of other individuals in the local community (vehicle collisions, etc.) and the least threat to the respondents’ own economic well-being (agriculture, personal property).”

The researchers sent out 4,500 questionnaires about the elk to local residents, and received 1,574 surveys back.

“Our preliminary results indicate widespread interest and even excitement for the idea among landowners and residents across every strata we sampled,” Fond du Lac wildlife biologist Mike Schrage recently told the St. Louis County Board of Commissioners, the Duluth News Tribune reported.

At least one county commissioner was opposed to the idea.

“I have spent the better part of a year studying this and, folks, to romanticize having elk in my backyard, I would love to,” commissioner Keith Nelson said. “But when you look at the realities of it and this nation proposing it to be put back into our tax-forfeited lands, it just does not make good common sense.”

Nelson pointed to conflicts between elk and people, especially farmers, in other areas where they have been reintroduced.

Home to roam

Elk are called omashkoozoog by Ojibwe people, which means “prairie moose.” The large member of the deer family usually populates grasslands and scrublands in the upper Midwest. A small population of elk lives in northwestern Minnesota, but the habitat and location has caused problems, as the animals have hurt agricultural crops grown in the same areas.

The areas selected for possible reintroduction are all assessed to have low risks of causing conflicts with humans.

It’s hoped that the young forests, barrens and other landscape types of the St. Louis River watershed might be able to sustain elk while keeping them away from farms. The animals particularly like to browse on young aspen trees, which most occur in the early stage of forest growth after disturbance like fire or logging.

The scientists used data about forest types and other habitat requirements to estimate how many elk could be supported in different parts of the area. They looked at both winter and summer foliage to get a picture of how the animals might fare all year around, sampling different plots to determine the nutritional value.

Ultimately, they found the three areas could support about 1,300 elk altogether. The possible habitat is believed to have the potential to sustain elk at densities similar to restored populations in Wisconsin and Michigan.

“Our findings show widespread suitable habitat and public support for elk restoration in northeastern Minnesota,” the researchers concluded. “Human-elk conflict risk is low on our study areas but is high in some nearby areas where a restored elk population might expand.”

MORE INFORMATION:

Potential places to reintroduce elk are identified in northeastern Minnesota