Wolves that have been transported to Isle Royale National Park as part of a plan to restore ecological balance to the island in Lake Superior seem to be making themselves at home. That’s according to a new report from the long-running wolf study at the site conducted by Michigan Technological University and the National Park Service.

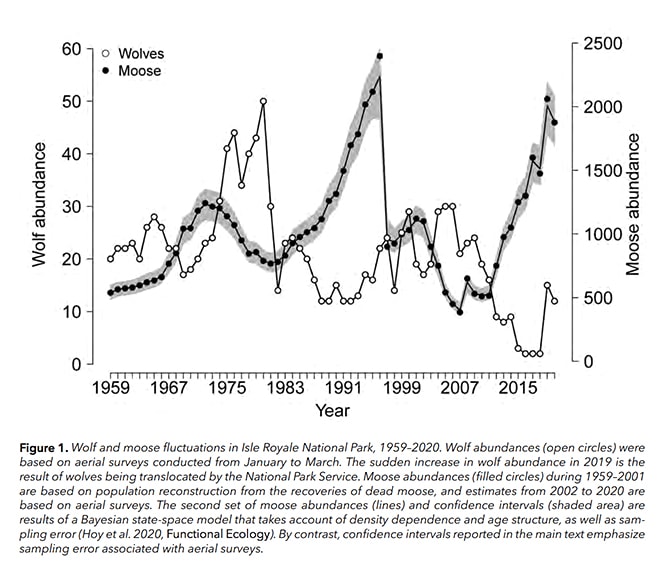

Nineteen wolves were captured from mainland sites in Michigan, Minnesota and Ontario starting in 2018 and released on Isle Royale. The island’s wolf population had dwindled to two animals at most, leading to an explosion in the moose population.

There are now believed to be about 12-14 wolves on the island, as some of the transported individuals have died, and at least one returned to the mainland via an ice bridge. There are also a couple wolves that may have gotten to the island on their own. Recent research has found that the wolves still there have given birth to pups, begun establishing social groups and territories, and the moose population seems to have leveled off.

“The wolf situation on Isle Royale remains dynamic as these wolves continue to work out their relationships with one another,” said Mark Romanski, U.S. National Park Service natural resources manager and biologist coordinating the wolf introduction program. “It is expected that social organization ought to settle down, but then again, wolves often don’t abide by human expectations.”

Because all the wolves that were transported to the island were fitted with GPS collars that broadcast their location, and ear tags that help identify them, biologists have been busy studying how they adapt to their new home.

Doing what wolves do

How these wolves – gathered from disparate locations around Lake Superior – would form social relationships was a key question at the beginning of the reintroduction effort.

Just last winter, location data indicated only three wolves had begun to coalesce into a pack, and the scientists now say four “social groups” formed over the winter. They can’t quite be considered packs yet, but the beginnings of such clans are evident. Two of the groups have claimed territory that encompasses most of the main island in Isle Royale’s archipelago. Two other groups have been occupying marginal territory.

Those packs have gotten right to work, killing several moose, both working collaboratively and solo.

“The kill rate is a relatively high for the number of wolves we have,” said researcher Rolf Peterson of Michigan Tech. “This is in part due to the fact that most of the wolves are in their own hunting unit, as opposed to being grouped into larger packs. The pairs kill moose and some of the single wolves kill moose. The wolves have killed roughly a moose every other day, or 25 kills in 48 days.”

Wolves appear to be one reason the moose population seems to have stabilized, after years of record growth in the absence of predators. From 2012 to 2019, the number of moose on the island grew approximately 19 percent each year. Researchers estimate it dropped nine percent last year. In addition to the new predators, as many as 100 moose starved last winter. Their high numbers mean much of their winter food sources have been depleted, particularly balsam fir.

A new generation

Perhaps most exciting is the presence of wolf pups. Based on GPS data, remote camera images, scat, and other signs, it appears there have been at least four pups born in the last year.

“Documenting reproduction is critical to the success of any introduction effort,” said Dr. Jerry Belant, a professor from the State University of New York who has assisted the National Park Service with the wolf reintroduction. “In contrast to 2019 where female wolf 014F was likely pregnant before translocation, the breeding and rearing of two litters of pups this spring was a major step toward their recovery.”

One of the wolves transported to the island is believed to have been pregnant when she arrived, and gave birth in spring 2019. Another wolf appears to have had pups this April.

The pups are of course born without GPS collars or ear tags, so they are harder to track. Researchers have collected numerous scat samples from den sites, though, and will perform genetic testing to determine relationships and learn more.

Mystery wolf

Another mystery is an adult wolf observed without GPS collar or ear tags. It’s possible, but unlikely, that a wolf brought to the island managed to get both its GPS collar and ear tags off (one wolf is known to have lost its GPS collar already). The other possibility is that the wolf found its own way to Isle Royale.

“One possibility is that a non-collared wolf arrived at Isle Royale by walking across an ice bridge in February 2019,” the report reads. “This possibility is also supported by observations reported in the 2018–2019 annual report which describes extensive tracks from what appear to have been at least three wolves that did not belong to other wolves known to be in the population at that time.”

It is hoped that ongoing DNA analysis of wolf scat from the island will eventually help identify this mystery wolf. It’s one of many questions that scientists and park managers will continue seeking answers for in the years ahead.

Isle Royale is home to the longest running predator-prey research project in the world, which has studied the relationship between wolves and moose for 60 years. With the wolves now restored to the island, it is also hoped researchers will continue to learn new things about the animals and their close relationship with moose.

More information

- Ecological Studies of Wolves on Isle Royale – Annual Report 2019-2020 (PDF) – Isle Royale Wolf Study

- Isle Royale Winter Study: Fewer Wolves, Fewer Moose – Michigan Tech

- Wolf Pups Born on Isle Royale – National Park Service

- Unknown Number Of Wolf Pups Born At Isle Royale National Park – National Parks Traveler