Legislation that would block mining on federal lands in the watershed of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness was the subject of a hearing in a House of Representatives subcommittee yesterday. The bill, authored by Rep. Betty McCollum of St. Paul, Minnesota, seeks to enact such a ban in Congress, while the executive branch has enacted, withdrawn, and initiated again such a policy through federal agencies over the past six years.

H.R. 2794, the “Boundary Waters Wilderness Protection and Pollution Prevention Act,” was heard in the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources. The remote hearing featured testimony from several witnesses and questions and discussion by lawmakers. It was chaired by Rep. Alan Lowenthal of California’s 47th district.

Both McCollum and Rep. Pete Stauber of Minnesota Eighth District, which includes the public lands and minerals in question, spoke at the hearing. McCollum is a member of the subcommittee and chairs another powerful appropriations subcommittee.

“The U.S. Forest Service is currently undertaking a science-based environmental analysis on the risks of this type of mining within the watershed, as part of a proposed 20-year mineral withdrawal,” McCollum said in a statement after the hearing. “The Natural Resources Committee is working in parallel to evaluate whether a permanent withdrawal is necessary to protect the BWCAW, our nation’s most visited wilderness and a priceless reserve of water so clean that you can drink directly from its lakes and rivers. Water is our most critical natural resource, and it must be protected not only for today, but for future generations. There is absolutely no room for error and no level of acceptable risk for toxic acid mine drainage within the watershed of this wilderness. Once damaged, it would be damaged forever.”

Other witnesses included Tom Tidwell, the former Chief of the U.S. Forest Service who originally proposed such a ban during the Obama administration, Steve Piragis, owner of Piragis Northwoods Company in Ely, Julia Ruelle, a board member of Kids for the Boundary Waters, and Julie Padilla, Chief Regulatory Officer for Twin Metals.

“The United States needs minerals,” Tidwell said. “But not from here. The risk is too great.”

Julia Ruelle shared a personal testimonial closing with “The Boundary Waters is a treasure, held in a delicate balance, preserved by the purity of the water. Our generation…would like to inherit the pristine and transformative wilderness enjoyed by generations before us – not a toxic superfund site, ruined forever, that my generation will have to clean up.”

Climate change impacts

Twin Metals, the only company with an advanced proposal in the region affected by the watershed ban, made the case that its mine would be good for the global environment and the Boundary Waters wilderness a couple miles away. Padilla referenced the need for copper and other metals for technology ranging from electric car batteries to wind turbines and which helps lower carbon emissions.

“The single most concerning threat to the Boundary Waters is not a modern mining operation – it’s climate change,” said Padilla. “Wishful thinking will not stop climate change. Only action will. And that action must include environmentally sensitive, modern mining of our resources where they exist.”

An analysis of Twin Metals’ greenhouse gas emissions conducted by the Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters in 2019 found that the project would release carbon dioxide and other compounds equivalent to adding about 165,000 gas-powered cars to the road. Last year, the Friends of the Boundary Waters said its analysis found Twin Metals would be like adding 89,000 to 235,000 passenger vehicles.

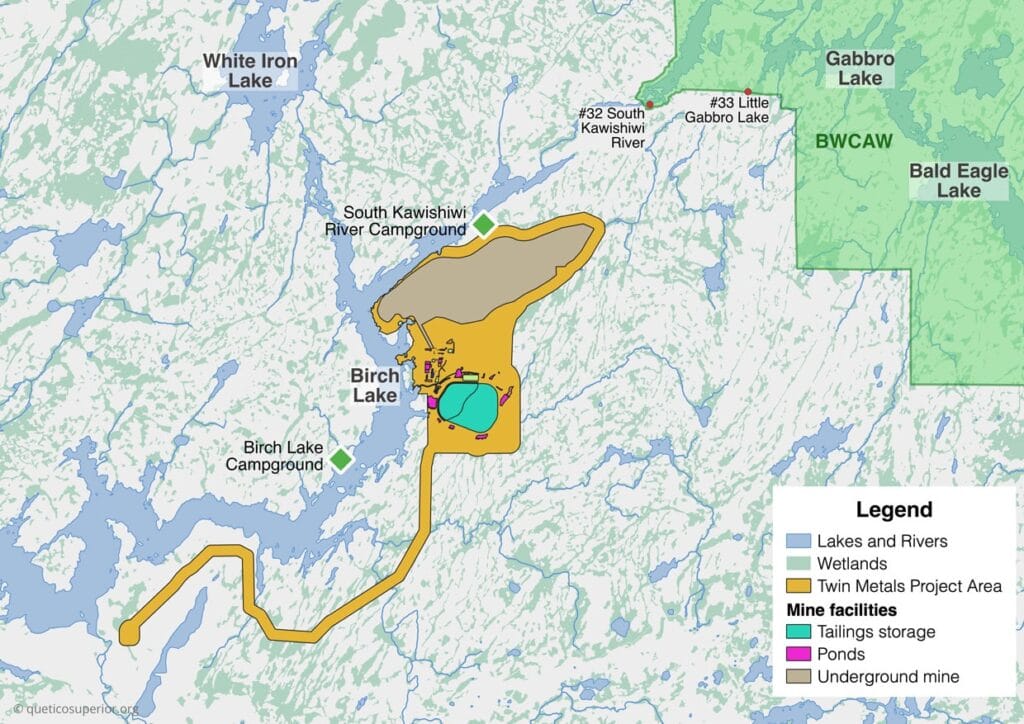

Padilla’s comments were echoed by Rep. Stauber, a supporter of copper-nickel mining since being elected in 2018. He claimed that the bill is misleading because no mining is proposed in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, where it is prohibited. The Twin Metals project would be about two miles from the wilderness, near the Gabbro Lake entry point. It would store waste on the surface in a pile a short distance from Birch Lake, part of the South Kawishiwi River.

“Northern Minnesota is uniquely positioned to develop the resources for America’s supply chains, as the International Energy Agency has stated in its report that six times more mining is needed for our modern lives,” Stauber told the committee. “My district alone contains 95 percent of America’s nickel, 88 percent of our cobalt, 75 percent of our platinum, and more than one-third of our copper.”

Stauber told the committee not to trust the bill’s sponsors and supporters, and that the proposed mine site was already accessible by road, not in a trackless wilderness.

Pollution potential

All the witnesses read prepared testimony that had been submitted to the committee in advance. But, despite a scripted proceeding, there was an unexpected twist. A change between what Padilla from Twin Metals had written and what she said during the hearing caused significant consternation.

Padilla’s written testimony submitted before the hearing originally said there was “no potential of acid rock drainage” from the Twin Metals mine. But the morning before the hearing, she provided revised written testimony with that line removed, the only change. It seemed the company was not confident in the statement.

Committee chair Lowenthal called attention to the change as soon as questioning began. He asked her to explain the change and which statement was true.

Padilla denied there was any difference, and responded “there is no risk of acid rock drainage to the Boundary Waters from this project.” She repeatedly restated the point, emphasizing the threat to the Boundary Waters. The only difference from her original testimony seemed to be that there is a possibility of acid rock drainage, just not affecting the wilderness area. The mine is upstream of numerous popular recreational lakes in the Superior National Forest, including the White Iron Chain outside Ely.

The slim margin for error with such mining near the nation’s most popular wilderness was a recurring theme of the bill supporters. Northern Minnesota is much wetter than other places in the United States where copper mining is conducted, and the area’s clear, cold lakes are especially sensitive to pollution.

“There is no room for error and no level of acceptable risk within this watershed,” McCollum said. “Once damaged, it would be damaged forever.”

Watch the full hearing:

More information:

- Subcommittee Hearing: EMR Legislative Hearing – May 24, 2022

- Hearing on Boundary Waters Bill Showcases Wide Support for Permanent Protection – Rep. Betty McCollum

- Stauber Opening Remarks at Legislative Hearing on Democrat Bill to Ban Mining in Part of Northern Minnesota – Rep. Pete Stauber