Fur trappers in northeastern Minnesota caught the lowest number of fishers this winter in at least 20 years. Biologists worry that this large member of the weasel family’s population is dwindling.

Fishers are about the size of a red fox, with shorter legs, and are highly effective predators that spend a lot of time in trees. Because they are primarily nocturnal and occupy deep forests, they are not often seen by humans. But they are well known to their prey: snowshoe hares, squirrels, and even porcupines.

Fishers are still trapped in Minnesota, though the season has been reduced in recent years. But reduced trapping may not be enough to save them. The animals are facing threats from a loss of habitat, and a changing ecosystem.

“It’s alarming,” Tom Rusch, DNR Tower Area Wildlife Manager, told The Timberjay. “We tried to adjust the season to get some bounce back… We just don’t have that 18-inch tree anymore, like we did when fisher were at their peak.”

Fishers depend on cavities in large aspens for nesting. Wildlife biologists point to changes in management of state lands in the region, with aspen stands being cut on a shorter rotation than previous, meaning there are fewer available trees for fishers to give birth and raise young. Older forests also tend to have more logs and brush on the ground, and diverse tree species and sizes, which seem to be ideal for feeding fishers. The unmanaged and unlogged forests of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness are believed to provide important habitat for the animals.

In addition to losing habitat, fishers are also affected by an increased bobcat population in the region. Bobcats thrive in the younger aspen forests, and can outcompete fishers, or kill them. Fishers are found throughout Minnesota’s wooded regions, though numbers are highest in northeastern Minnesota.

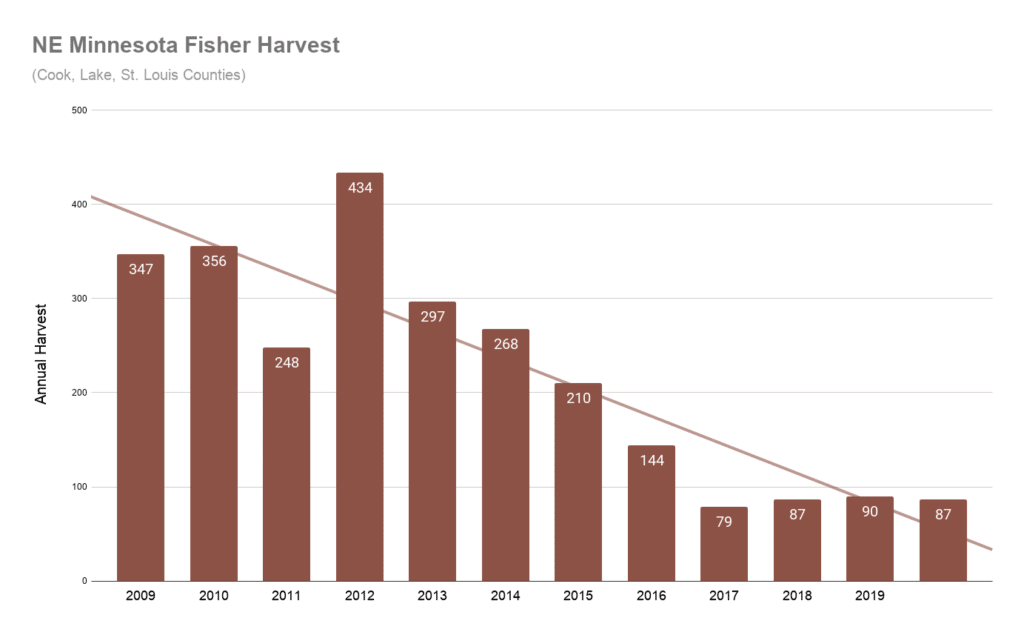

Trapping provides important annual information about fisher populations. The season was reduced from 16 days to nine days in 2007, and then cut to six days five years later. In 2019, the season was increased back to nine days. The limit was reduced from five to two per season in 2010.

The harvest decline also correlates with other studies of populations, including surveying for tracks. In the most recent report on track studies, in 2019, the DNR reported fishers were far fewer.

“[F]isher indices have remained below their long-term average for the past 12 years, and far below the long-term peak around 2002,” bioogist John Erb wrote.

In 2019, tracks were seen along just six percent of the route segments and along 69 percent of the routes overall. That was down from a peak of 14 percent of route segments and 78 percent of the survey routes at its peak in 2002.

One innovative research project underway is trying to better identify the causes for fisher declines and test a method for helping them survive. Scientists at the University of Minnesota’s Natural Resources Research Institute have nailed nearly 100 artificial nest boxes to trees around northern Minnesota and are trying to see if female fishers will use them for raising a brood.

The researchers have documented fishers visiting the boxes using camera traps and other methods, but there has not been any sign of nesting yet. Previous studies elsewhere have shown fishers seem to get used to them slowly, and use for nesting increases over the first few years after placement.

More information:

- Trappers report lowest fisher numbers in twenty years – The Timberjay

- Fisher (Martes pennanti) – Natural Resources Research Institute

- Fisher – Minnesota DNR

- Trapping & Furbearers – Minnesota DNR