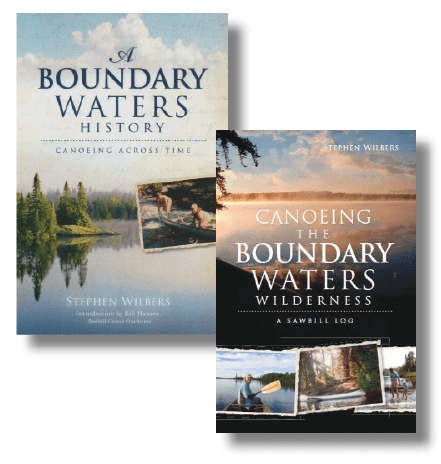

There is the Boundary Waters, there are the people who go there, and at the intersection of those two is where canoe country exists. Though wilderness is a place where “man himself is a visitor who does not remain,” we experience it as humans, perceiving it with our subjective senses, through the lens of our own personal histories. So it is natural how Stephen Wilbers joins his stories to the land in A Boundary Waters History (History Press, 2011) and Canoeing the Boundary Waters Wilderness: A Sawbill Log (History Press, 2012).

In these books, Wilbers describes three decades of canoeing the region with his father, his children, and a rotating cast of other friends and family. Wilbers’ personal history, written on the northern landscape, cements the wild to the human. It is clear that for the author, the Boundary Waters contains milestones marking the progress of his life. On a trip in 1983, his first with his four-year-old son Eddy, they return to a campsite on Hazel Lake that Wilbers had stayed at three years before. The fact that it looked just the same inspires reflection on his own life, “Camping there now made me realize how much life had changed since Eddy’s birth. Debbie and I had become parents to not only a son but also a daughter, I had changed jobs twice, and we had moved from Iowa City to Minneapolis.”

Years later, when they camp on South Temperance Lake, Wilbers recalls that they last stayed on this site six years ago, when Eddy was just five years old and Wilbers’ dad was getting ready to retire. But more years go by and, after a hard and rainy trip with his now-teenage son ends in cross words, Eddy doesn’t rejoin him for seven years. The next year is the first time Wilbers does not record a trip journal, saying only that he “wasn’t in the mood.” Time quietly passing and people inevitably changing stands in sharp relief to the steadfast landscape.

The melancholy that comes with seeing kids growing up and parents growing old is sweetened by the fact that canoe country is clearly where some of Wilbers’ fondest memories with loved ones reside. Familiar sights like a big rock, a tree, or a portage are not just places, but stories. On the first year Eddy is back, a jubilant Wilbers writes about returning to his “favorite campsite on his favorite lake in the Boundary Waters.” He pauses and admires the view from his son’s “lookout tree,” where the boy had once spent hours watching the lake.

Wilbers is a teacher of writing and the author of books and newspaper columns about writing well, so it shouldn’t be surprising that his prose is pleasingly clear, straightforward, and full of immediacy. He kept careful journals during his trips, and the books are largely comprised of revised entries. These logs are rich in the sorts of fleeting moments, sights, reflections that are essential to capturing the magic of a trip.

Much has been written about the Boundary Waters, and it could be daunting as a writer to seek a place in the canoe country canon. But Wilbers claims his place with grace, avoiding redundancy by frequently quoting from many other writers. He has clearly read just about everything that has been written about the Boundary Waters, and frequently finds occasion to augment his observations with excerpts from other writers and wilderness characters.

While this may not be the philosophical prose of Sigurd Olson or Paul Gruchow, it carries its own weight. The central idea quietly woven through the text is that going to the Boundary Waters is going home, that the demands of simple survival are enough to strip away the nonsense of the modern world, and connect us with something old in ourselves, and with our companions.

This article also appeared in Wilderness News Summer 2014, View and Download a PDF Here >