The legacy of Jack Rajala lives on through millions of seedlings. The longtime northern Minnesota lumberman and community leader loved long-lived tree species like white pine and cedar. Although he passed away in 2016, his work continues through a nonprofit that is dedicated to the future of the trees he cherished.

The Rajala Woods Foundation began as an initiative of Minnesota Power after Rajala’s death. The company pledged to plant three million seedlings across the 30,000 acres of land it owns as a living memorial to Rajala, who served on its board of directors for decades. A year after launching, with enthusiasm and excitement building, the initiative became a standalone nonprofit organization. Today, the organization owns or manages forests across northern Minnesota, and has worked on reclaimed mine pits, a cemetery, and two special preserves where they are not just restoring the forest, but studying and learning new techniques to help forests thrive in the future.

There are many kinds of trees that call northern Minnesota home. Rajala Woods is focused on helping a few species that take a long time to grow to maturity, and which have been decimated by decades of unsustainable logging, climate change, ecosystem shifts, and other forces.

“RWF is laser-focused on restoring northern forests to reflect their original species composition, and we are working on ways to accelerate the timeframe for getting these trees established,” says executive director Blake Francis.

A living legacy

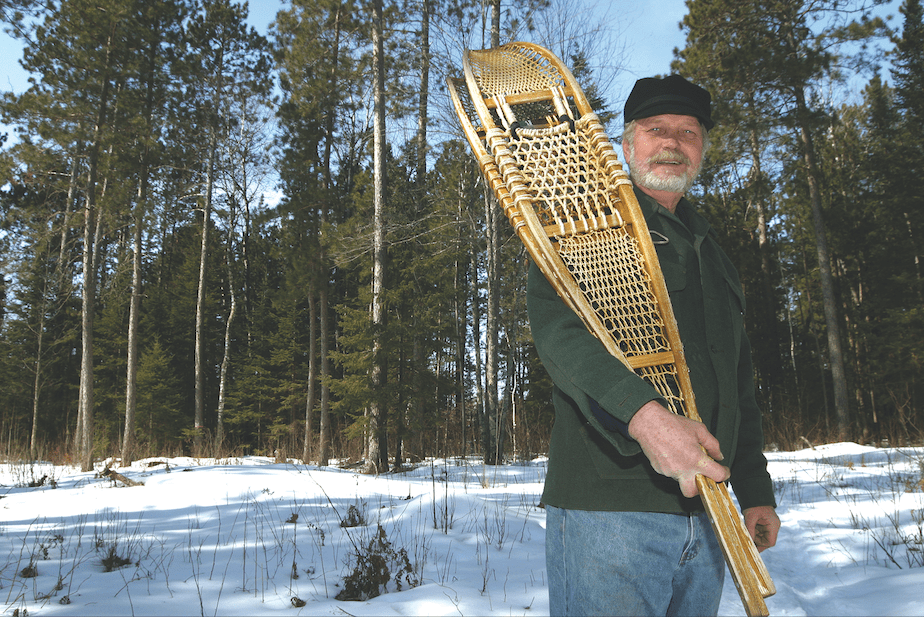

Jack Rajala ran Rajala Forestry, a Deer River-based company his family has operated for more than 100 years, from the 1960s to his retirement in 2010. In that time, he helped launch an effort to plant almost four million white pine seedlings on the company’s timberland. It was both an attempt to restore the forest and ensure the long-term future of the logging company.

“The majesty of them, even when they’re young—that means a lot to me emotionally and spiritually,” he told Wilderness News in 2008. “These trees have a way of responding, almost as if they were looking, saying, ‘we need you, we need you.’”

The challenge the trees needed help with was regeneration. The Rajalas and others saw that, even when replanted, the white pine forests weren’t coming back. It was both a loss of iconic and beautiful trees, and a dire situation for sawmills that needed logs.

More than a century of lumbering in northern Minnesota didn’t just remove trees, it upset the entire ecosystem. By opening up large tracts of forest and converting them to short-lived trees like aspen, the population of white-tailed deer ballooned. Deer simply devour young white pines and cedars. In addition to young trees getting killed by deer, there also just weren’t enough seeds left on the landscape to grow new trees.

While many foresters were giving up on bringing back white pine in the 1970s and 1980s, Jack Rajala refused to quit. He eventually landed on the simple method of “bud capping” to protect saplings — stapling a piece of white paper over the tip of the young tree to protect it from deer. It’s simple, but it takes enormous time and effort. It also works. He published a book in 1998 called “Bringing Back the White Pine” to detail his experiences and discoveries.

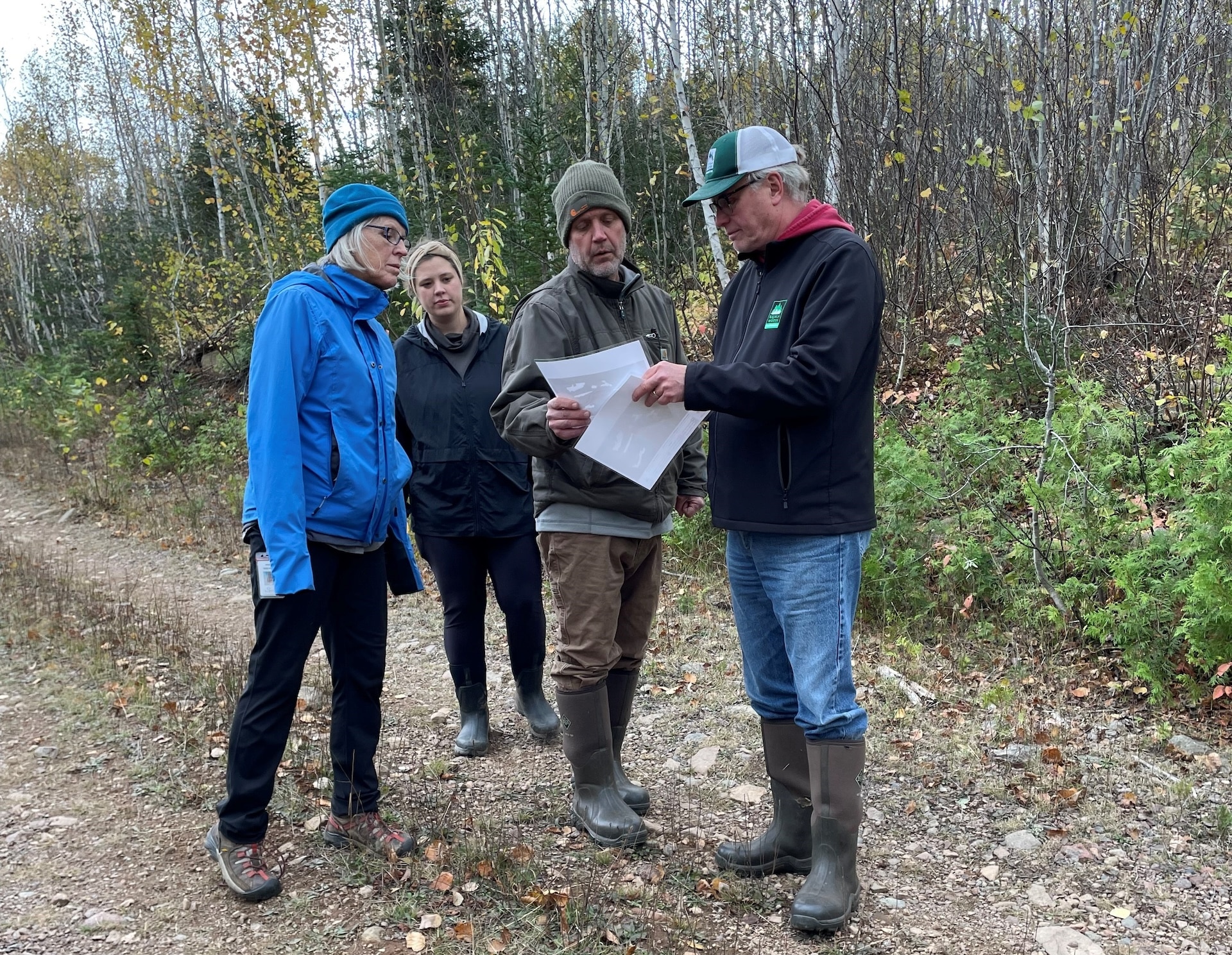

And Jack kept planting pines. Today, Rajala’s family continues to run the company, now called Minnesota Timber & Millwork, while also helping the foundation with its tree cultivation. His son, John Rajala, and granddaughter, Claire Vatalaro, are both members of the RWF board of directors.

Forest focus

The sharp focus of Rajala Woods Foundation on restoring forests and returning to more balanced species composition has seen significant results over the seven years since its founding. The group has partnered with others — private property owners, public agencies, nonprofit organizations — to plant trees, and sow the seeds for more sustainable forestry in the future.

Most of Rajala Woods Foundation’s work in 2023 took place at its 1,200-acre Moose Creek property, in eastern Lake County, where the group is working to “reboot” the forest. The land is adjacent to the Superior National Forest, surrounded by other parcels owned by the state, county, and private individuals. It spans more than two miles across a valley containing Moose and Ninemile Creeks, tributaries of the Manitou River.

It’s a prime opportunity for restoration, the group says, because the forest would otherwise be stuck in an endless cycle of aspen growth and harvest. The site was logged about 20 years ago, and was thick with fast-growing, short-lived aspen when Rajala Woods acquired it.

“Without our involvement, the aspen would stay the dominant species, likely for centuries,” Francis says. “That aspen would be harvested after reaching commercially valuable size, and the harvested area would naturally revegetate with more aspen.”

But, rather than cutting down a lot of aspen that weren’t ready for harvest yet, the group left a lot of it standing. They instead thinned the forest and then planted red and white pines among the remaining aspen. Crews returned in the fall to cut back vegetation around the plantings. While the aspen mature over the next two or three decades, the pines will get more sunlight and a jump-start on growth.

‘Deer desert’

Rajala Woods foresters also saw something surprising at Moose Creek: there are fewer deer in this forest in the Lake Superior highlands than much of northern Minnesota. That presents an opportunity to help at least two types of trees. One is white cedar, which can live as long as 400 years.

“Deer like to browse on white pines, but they love to eat young cedar. [The] Moose Creek Project is located in a ‘deer desert,’ which could be extremely helpful for our initiatives,” says board chair Kurt Anderson.

The high ridges along Minnesota’s North Shore are often buried in deep snow, caused by the meeting of cold air and warmer water over Lake Superior. According to the Department of Natural Resources, areas within five miles of the big lake get on average 10 more inches of snow than the surrounding region each winter. More snow means fewer deer, and better chances for white pine and cedar.

Based on this new knowledge, Rajala Woods is working this year to establish more white cedar on the Moose Creek property.

They’re also trying new things and figuring out what works in other ways. Last year, Rajala Woods helped plant 95,000 red pines at a reclaimed taconite mine site, experimenting with soil amendments including biochar and compost. They are monitoring the project to inform future work, and the mine owner is considering seeking carbon credits to account for the offset in greenhouse gasses.

Near Hoyt Lakes, in St. Louis County, the Rajala Woods-owned Hodnik Family Forest is also prime for red and white pine. Previously logged, the group says the soil is ideal for the tree species. The land was donated by Minnesota Power’s parent company, ALLETE, in honor of its former CEO Al Hodnik and his family. The group is working on a forest management plan and will then get to work on the woods.

Planting progress: three million trees

The original goal of planting three million trees in honor of Jack Rajala in the decade after his death has nearly been met, with a few years to spare. Meanwhile, the foundation that grew out of his love for northern Minnesota’s forests has expanded the effort.

“Inspired by the ‘can-do’ attitude of Jack Rajala, who helped regenerate white pine when many didn’t think it was possible, RWF has made it our mission to carry-on and expand that legacy – and Jack’s never quit attitude,” says Francis.

One tree at a time, Rajala Woods Foundation is bringing new life to old forests.