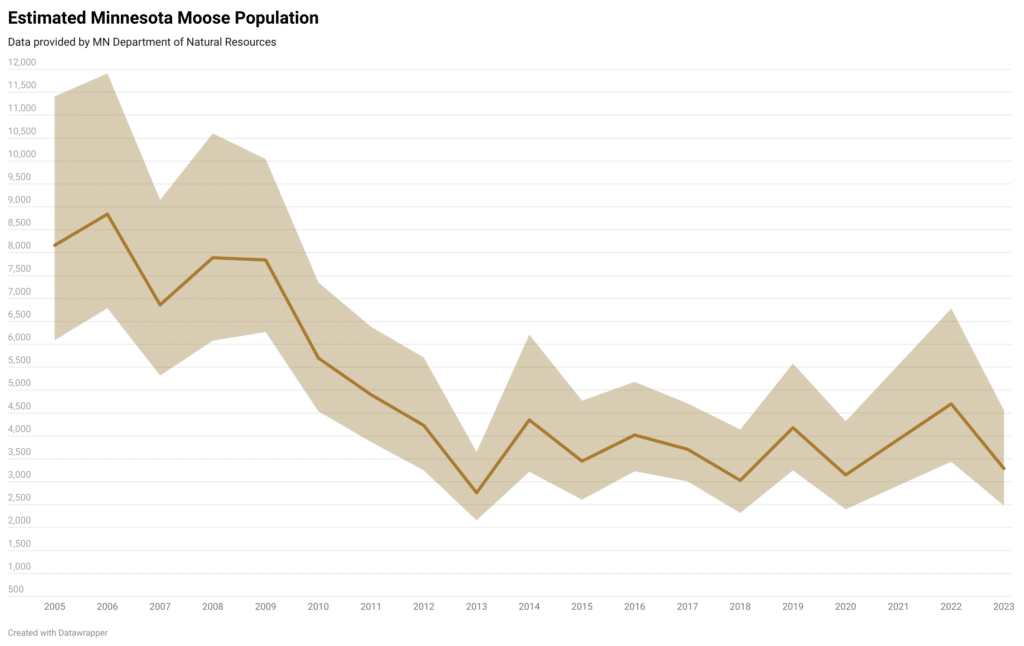

It’s been about 15 years since wildlife biologists first noticed a sharp drop in northeastern Minnesota’s moose population. After peaking at about 8,800 animals in 2006, the number of the animals fell drastically over the next five or so years, bottoming out at about 2,760 moose in 2013.

Since then, the estimated population has shown annual variation between about 3,000 and 5,000 moose. This winter’s survey has come up with an estimate of 3,290 animals. The Department of Natural Resources says the number represents a steady herd size, with some cause for concern.

Rough estimate

“This year’s population estimate is down 30% from last year’s point estimate,” wrote the DNR’s John Giudice. “However, sampling uncertainty is moderately high in this survey and, thus, it is often difficult to make statistically confident statements about the magnitude of annual population changes unless those changes are relatively large.”

The moose population is surveyed every winter by aircraft. Two observers join a pilot flying over designated plots of forest in northeastern Minnesota, spread across nearly 6,000 square miles including the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, counting any moose they see. The DNR develops the population estimate based on statistical analysis based on their observations.

Biologists warn that the surveys provide fairly rough estimates of the population, primarily useful for seeing large changes in the herd and observing long-term trends.

Calf concerns

The DNR also notes that its partners at the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa have provided other data that add nuance to the assessment. They said that band researchers have recently observed high mortality of moose they are tracking using GPS collars, perhaps indicating this year’s decline is more than a statistical anomaly.

“It’s abysmal. I think this is the worst calf recruitment year we’ve seen in 12 years of study,” Grand Portage biologist Seth Moore told WTIP last July. “Essentially, of our collared moose, 100 percent of the calves are gone.”

Last fall, the band announced it would cancel its plans for issuing permits to harvest up to 21 bull moose in areas where it has rights protected by treaties.

There are several reasons biologists suspect the moose population remains lower than 20 years ago. Research has shown that climate change, parasites carried by white-tailed deer, and predation by black bears and wolves are factors.

The survival of moose calves from birth to one year has emerged as a key point. The DNR and its partners note that, while pregnant moose cows remain abundant, calf survival has remained low. Studies over the past decade have found that as few as one in three moose calves survive to maturity. The scientists have seen that wolves account for about two thirds of moose calf deaths.