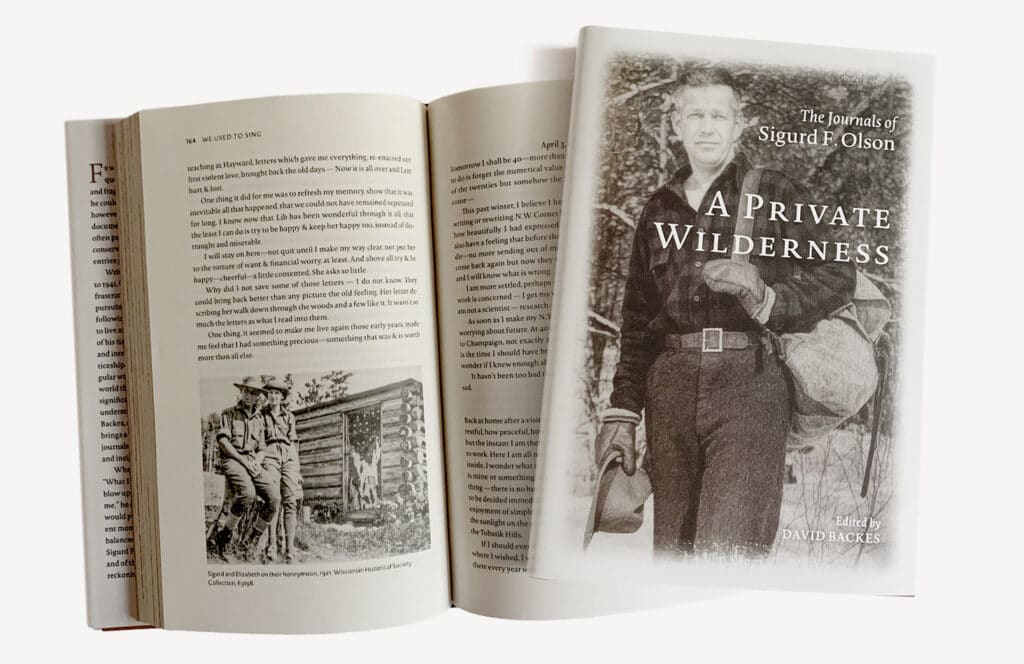

A Private Wilderness The Journals of Sigurd F. Olson

Author: Sigurd F. Olson

Edited by David Backes

University of Minnesota Press

The first decades of Sigurd Olson’s writing life were filled with frustration and hope, failure and doubt, and finally, publication. The new collection of his journals from this painful and formative time, A Private Wilderness, edited by David Backes, reveals a writer whose life was defined by the struggle between his calling and his many commitments.

While Olson eventually became a beloved and bestselling author, his first book was not published until he was 56 years old. Up until then, he had published some stories and articles in outdoor magazines, but fought for the time and energy to dedicate to the craft as he helped raise his children, worked as a teacher and then dean of the Ely Junior College, and operated a guiding and outfitting business.

All along, he just wanted to write.

“The struggle was so painful, as you can see in his journal entries. He really needed encouragement from people who seemed to come along at the right time to keep him going,” Backes said.

‘I must write’

By the time Olson was 30 years old, he had decided his purpose in life was to write about nature. It was the first step in becoming the cherished author he would become more than 20 years later. Backes says that is a critical lesson for anyone, that we can best contribute to society when we know who we are.

First and foremost, Backes said what was important was that Olson figured out who he was, and how he could best affect the world. In his 20s, he decided that documenting and sharing the joy and wonder he experienced in the woods through writing was his life’s calling.

Nature had been an important part of his life since childhood, most spent in northern Wisconsin. He grew up with a strict and intense father who was a fundamentalist Swedish pastor, who had specific ideas he forcefully pushed for what he considered were acceptable careers.

Going outside seemed to take away the stress of his home life.

“Nature continued to a source of great comfort and peace for him,” Backes says. “It would take away anxiety and it seemed to point him toward something really important, and he felt he had to capture that.”

By the time he was a young man, wilderness and writing were wedded in his personality.

“This I know, that I must write and I must live out of doors,” he wrote in 1930. “I must write. I cannot live and not write.”

But figuring out what he wanted to do was just the beginning.

The journal entries can be difficult to read at times, full of despair, but it helps knowing it was all worth it. Olson ultimately achieved his dreams, and more. It must have been greatly rewarding, for he had long believed that popular success would lift his worries and burdens and let him be truly happy.

“True happiness comes only to those who realize what they want and attain it,” Olson wrote.

His desire to write meant making difficult decisions and sacrifices. When the journals begin, he is struggling with decisions about his career. He is being urged to study zoology and become a scientist. It might seem like a natural fit for the curious and experienced woodsman, but Olson thought nothing could be more boring.

“In me it is far more worthwhile to feel the glory of a sunny morning on the snow than it is to obtain a new specimen,” Olson wrote.

While he was writing his journals and trying to chart a career as an author, he looked for inspiration from his peers and predecessors. He frequently compares his thoughts and passions to those of John Burroughs and Henry David Thoreau. He sees in their example that his talents were more than just being able to write the type of fishing and hunting stories that were popular at the time.

When his debut essay collection The Singing Wilderness was published in 1956, Olson became one of the most well-known voices advocating for the protection of America’s natural spaces. But he toiled in obscurity for a long time before achieving that status.

Money and medium

In the 1930s, there was little market for the lyrical observational essays about the canoe country wilderness that Olson recognized as his strongest style. Few people wrote anything comparable to his essays, and he didn’t know if he should stick with it, or attempt another format.

Olson dreamed of publishing a short story in the Saturday Evening Post. The publication paid so well he thought it would mean he could safely quit his job and dedicate himself to writing full time.

But it took him years to write an acceptable piece of fiction, and meanwhile his other work was either low paying or not enjoyable.

“You can be very good at writing one kind of writing, but that but doesn’t mean you’ll be good at another kind,” Backes says.

Olson’s marriage suffered, with the word “divorce” appearing in the journals multiple times. He recognized he was an irritable father when he wasn’t writing regularly. He even mentions suicide more than once.

Olson struggled not only find time to write, but space. He spent several years writing at either an abandoned cabin in the wilderness, which he would ski to, or in the house’s upstairs bedroom. At home, he was distracted by his wife and children’s noisy habits, but also felt bad for his loud typewriter.

“I never seemed able to settle down to my writing in the house, always afraid of disturbing someone, always conscious of the fact that my racket kept others on edge,” he wrote in 1937.

That was when he decided to build himself a writing shack, converting an old garage on the property for four-season use with a woodstove and a desk. It cost him about $150 and a lot of stress about the value of the investment, but believed it was also necessary to finally determine if he could make it as a writer.

“It is a tragedy that one should have to think of the financial end of things to the exclusion of all else,” he writes while watching costs add up for a garage conversion.

The journals are full of careful calculations about time, words, and money. He notes how many words he can write or edit in a two- or four-hour block of time. He compares this to the rates paid by various publications, and the costs of his office. He resents all of it.

Post-war progress

The journals focus almost entirely on his wishes and work to become a professional writer. There are glimmers of his lyrical and philosophical reflections on outdoor adventures, but most is dedicated to documenting his writing ambitions. He was constantly learning, improving his skills, and figuring out where his voice fit in the worlds of literature, outdoors writing, and conservation.

Then, World War II began, and the world’s attention turned to defeating fascism. Olson ended up overseas as a civilian teacher for a year in 1945. When he came back and the world began emerging from the war, he was pulled into a new battle: the effort to stop airplanes from flying over and landing in what is now the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

Olson quickly became a nationally-known wilderness advocate with his successful effort to prohibit aircraft. It could have been another distraction from his real goal as a writer, but his conservation work ultimately led to his long-sought success as an author.

Becoming known as an inspiring public speaker, Olson shared his wilderness philosophy with audiences across the United States. In one of those audiences was the publisher Alfred Knopf, who sent a letter to Olson afterwards, asking him for a book proposal.

The rest is history. Olson quit journaling about the same time he started finding success as a writer and conservationist. His later life was documented in the public sphere, as a prominent and prolific writer and wilderness proponent during the 1950s and 1960s.

Nonetheless, even the conservation work that garnered him accolades, and provided the prominence to become the author he had always wanted to be, eventually became another bothersome obligation.

But Backes says Olson knew he was fortunate to be involved in conservation at a time of great opportunity. He was a leader in the movement in the 1960s as one of the greatest periods of land preservation dawned.

Wilderness and a sense of self

It still cost his writing career. Even with successful books to his name, Olson again began complaining in his private pages about not having enough time to write.

“I’m sure he would have written a couple more books if he had given up his conservation work in the early 1960s,” Backes said. But that was not an option.

Olson passed away in 1982 from a heart attack while he was snowshoeing. His work had inspired many to pick up a paddle and explore the Border Lakes. He had helped protect many special places as public land. He had written many excellent essays and published many popular books.

Four decades later, wilderness is only more precious, and the threats to it continue. Backes says Olson still has something important to say.

“His philosophy is still urgent, it comes back to listening. We’re in a lot of trouble as a species and as a society, because we’re not listening adequately, at least those with power to change things,” he says. “We have become even more detached from nature than in Sig’s time, and when we’re detached from nature, we’re detached from our true selves.”

Being true to yourself is the key message of the journals, David Backes says. Olson figured out what made him happy, and kept pursuing it past the point when many might have quit. Thankfully, he never gave up.

“There’s a message of hope it can give to anyone today that they have a dream, a sense of calling,” Backes says. “Any good calling is not going to be easy to follow.”

Because of Olson’s perserverance, his legacy lives on. His inspiring Listening Point cabin on Burntside Lake and his home and writing shack are owned and managed by the Listening Point Foundation. His books are still beloved. And the wilderness remains wild.

More information:

- A Private Wilderness: The Journals of Sigurd F. Olson, 2021, edited by David Backes, University of Minnesota Press

- About Sigurd Olson – Listening Point Foundation