An Ely nonprofit and an Ojibwe band in northeastern Minnesota have worked together to create a new map showing traditional names for more than 100 lakes, rivers, and other places. The project benefited from a unique archive of the original names, which were largely replaced by European settlers in the nineteenth century.

The new map was recently released by the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa and the Ely Folk School. It was the result of two years of work by several individuals.

“This map highlights our region’s native heritage and our Ojibwe ancestors who’ve lived here for hundreds of years,” said folk school board member and Bois Forte band member Rick Anderson.

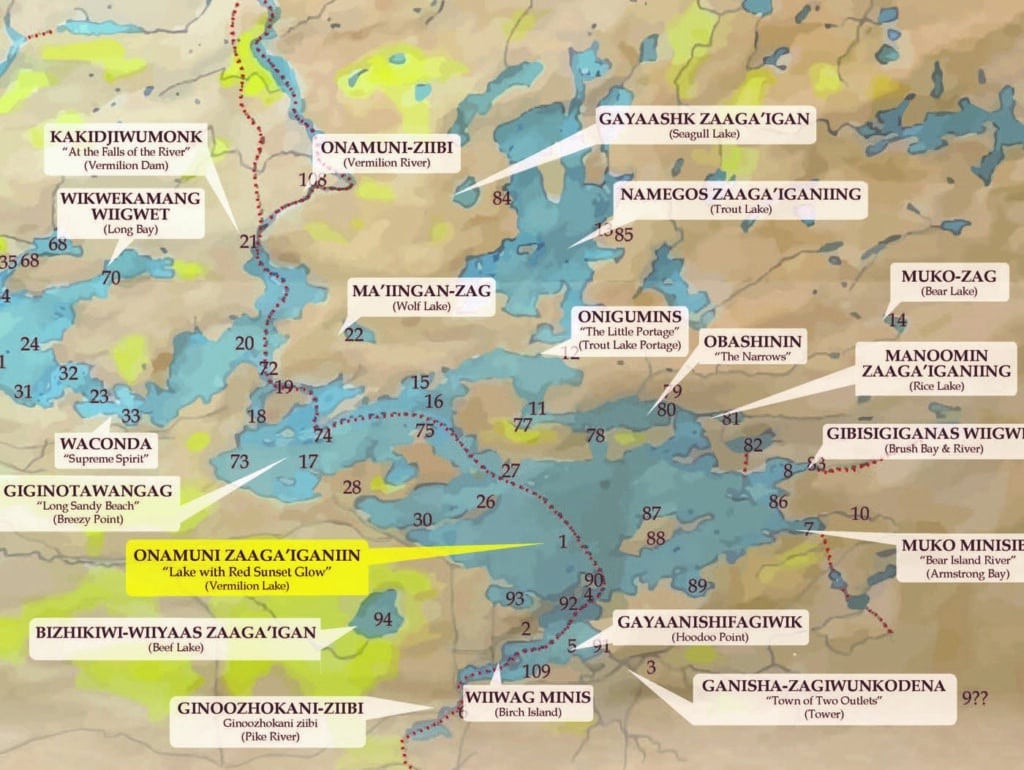

The map was designed by Bois Forte artist Louise Isham and crafted by map maker Keith Myrmel. It currently focuses on the area around Lake Vermilion and west toward Nett Lake, the Bois Forte Band’s traditional territory. Plans are in the works to possibly expand it to cover more of the Arrowhead region, as well as possibly creating an online version.

“We want to be able to reach a broad audience with this project,” said artist Isham. “A lot of hard work has gone into this project, and we want to ensure its long-term success as it will help the public better understand Bois Forte’s history and the lakes that are so important to our people.”

The project began with a growing relationship between the folk school and the band, including classes in traditional birchbark canoe making. As a result of the partnership, folk school members paddled across the international border in 2019 to attend the Lac La Croix First Nation pow-wow in 2019, where they met with First Nation members. They learned about a similar project completed by the First Nation to document Native names for places in Quetico, and decided to try following suit.

“Perhaps someday we’ll extend this map to include much of the Arrowhead and the Boundary Waters,” said Folk School board member Paul Schurke. “Too many original descriptive lake names were replaced with names of lumberjack’s love interest.”

One key resource that made the project possible was the work of a missionary in the 1870s. Irish-born Joseph Gilfillan, who spoke fluent Ojibwe, documented hundreds of place names while living in the area. Those journals have been preserved by the Smithsonian, and were referenced extensively.

In an 1885 report to the Minnesota Historical Society, Gilfillan explained why he believed documenting Indigenous names was important.

“The Ojibway Indian is a very close observer, a name either of a person or a place with him always means something, and is never a mere arbitrary designation as with us, but expresses the real essence of the thing, or its dominating idea as it appears to him,” Gilfillan wrote.

He also pointed to the similarities with his native land, where the Celtic people had been wiped out by Anglo-Saxons, but whose ancient names had held on in many places.

Currently, a limited edition of the new map is available to donors to the Ely Folk School. Mass produced prints will be released in the future.

Correction: Statements about the Folk School and Bois Forte Band’s birchbark canoe building partnership and the canoe trip to the Lac La Croix First Nation have been updated for accuracy.

More information:

- Bois Forte Native Names Map – Ely Folk School

- New map restores Native names to northern Minnesota – MPR News