A set of nearly 100-year-old handwoven mats recently made the voyage from Isle Royale to Grand Portage National Monument in northern Minnesota. The cultural crafts known as anaakanan will join a growing collection at the site jointly managed by the National Park Service and Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

“The park was honored to protect these mats over the years and appreciates the collaboration with the Grand Portage Band and Grand Portage National Monument to now host all seventeen mats together,” said Isle Royale National Park Superintendent, Denice Swanke.

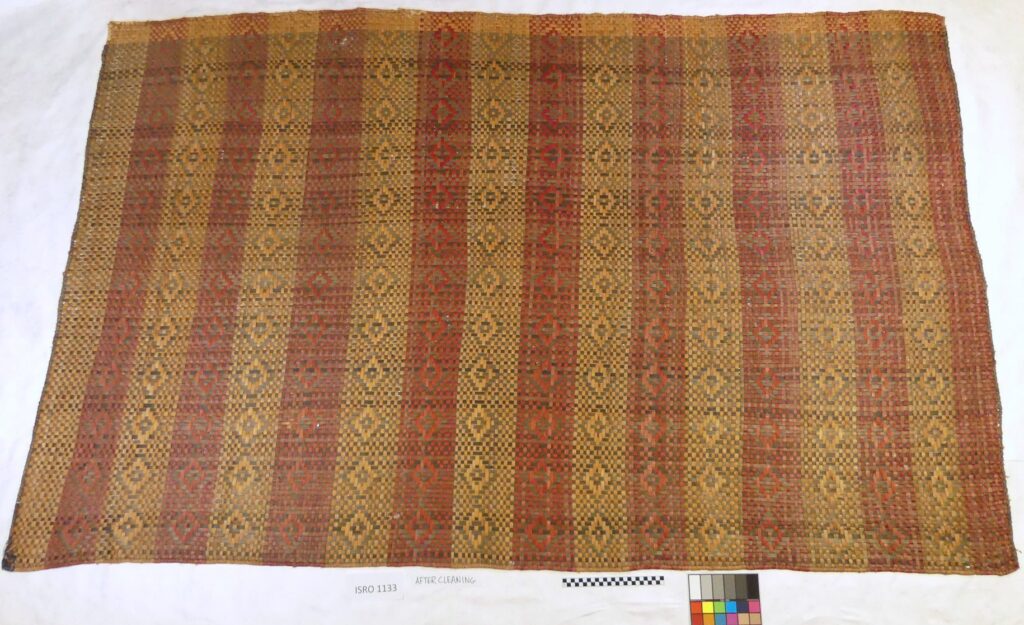

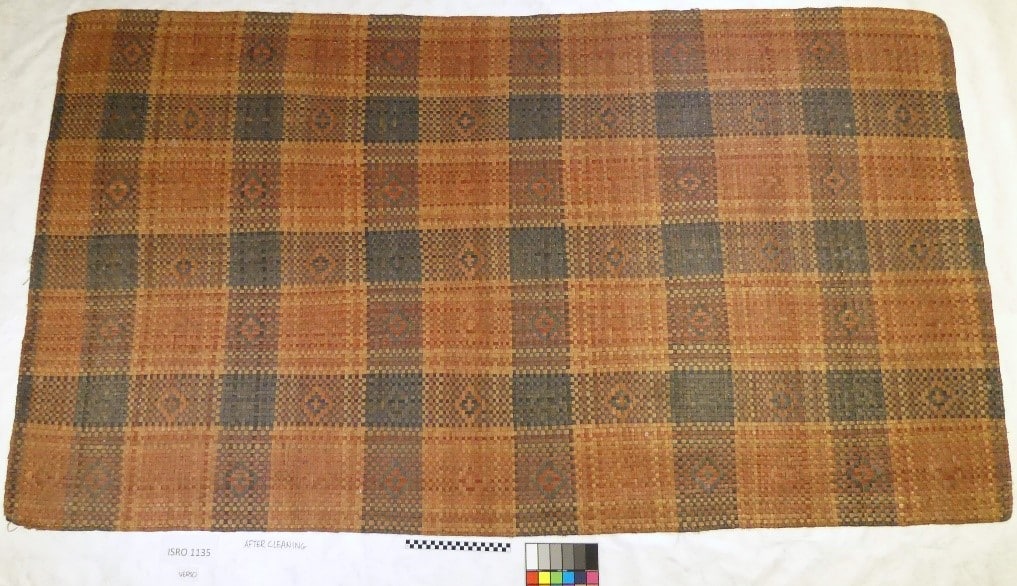

Some of the mats were made in the 1920s and 1930s by Helen Robinson Linklater, Tchi-ki-wis, an Ojibwe woman originally from the Lac La Croix area. Tchi-ki-wis and her husband operated a fishery on Isle Royale between 1927 and 1933, and Tchi-ki-wis often sold mats to tourists. The Linklaters are thought to be the last Native Americans to work and live on Isle Royale.

When the park was formed in the 1940s, island cabin-owner Frank Warren donated an extensive collection of indigenous items to the National Park Service, including the anaakanan. They will now be on an indefinite loan to Grand Portage.

“We wanted all the mats together in one place, especially if we find out that Linklater made them all,” Isle Royale National Park’s chief of Interpretation and Cultural Resources Liz Valencia told WTIP. “It could be the largest collection of hand woven mats by one person in the Great Lakes, or perhaps North America.”

The mats were welcomed to Grand Portage by park staff and band members after a 60-mile voyage aboard the park’s 22-foot boat Wolf from the park’s summer headquarters on Mott Island. Tribal council member John Morrin provided a culturally-appropriate reception. They will join another dozen mats in Grand Portage’s collection, including others by Tchi-ki-wis, four of them also from Isle Royale’s collection.

Experts say the artfully woven mats and their history exemplify the connection between Ojibwe people, who have lived along the North Shore for centuries, and the large island 20 miles off shore.

Last year, the indigenous significance of Isle Royale was recognized by the federal government as a Traditional Cultural Property, noting that people had been living on and visiting the site since long before European immigration.

“[The collection] documents historic connections, and continued modern connections to Isle Royale,” Valencia told WTIP. “This connection is still there today and it’s very strong.”

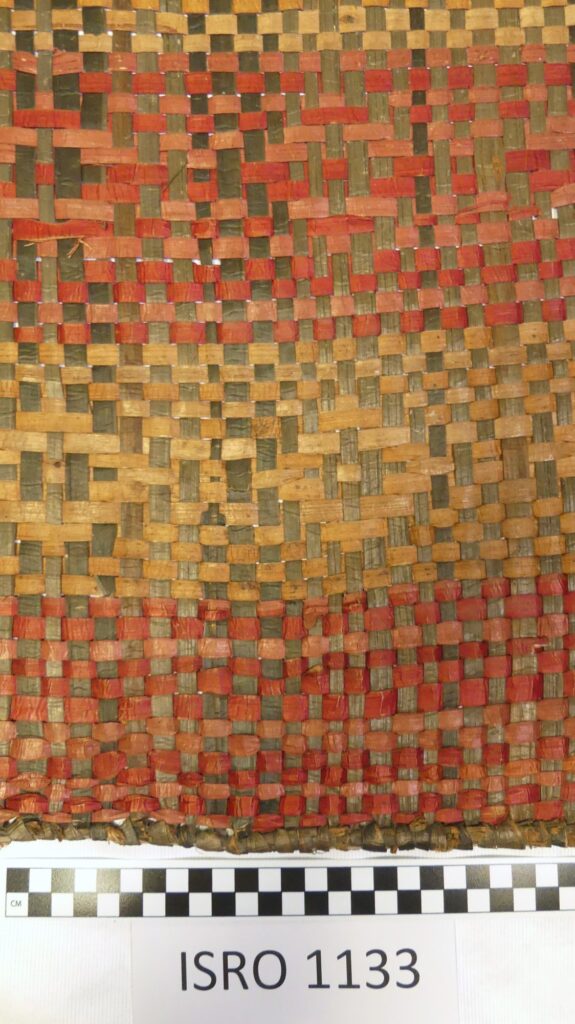

The mats recently loaned to Grand Portage were made primarily from the inner bark of northern white cedar trees, with one being made from sweetgrass. They were carefully prepared for their journey from Isle Royale to Grand Portage. Park staff consulted with National Park Service experts about the best methods for transport, rolling four of the mats that were flexible enough, and transporting one flat in a cardboard case.

Woven mats served both form and function. They were used on the floors of cabins or tents, as well as when working outdoors. But they also feature traditional designs with important significance.

“Designs were really important, intricate part of those mats,” Valencia said. “They weren’t just making mats to use on the floor, they were works of art.”

More information:

- Isle Royale National Park Delivers Handwoven Mats to Grand Portage National Monument – National Park Service

- Isle Royale Mats Loaned to Grand Portage – WTIP

- Isle Royale National Park Cultural Resource Interactive Mapping Project

- Isle Royale: Birch Island Fishery