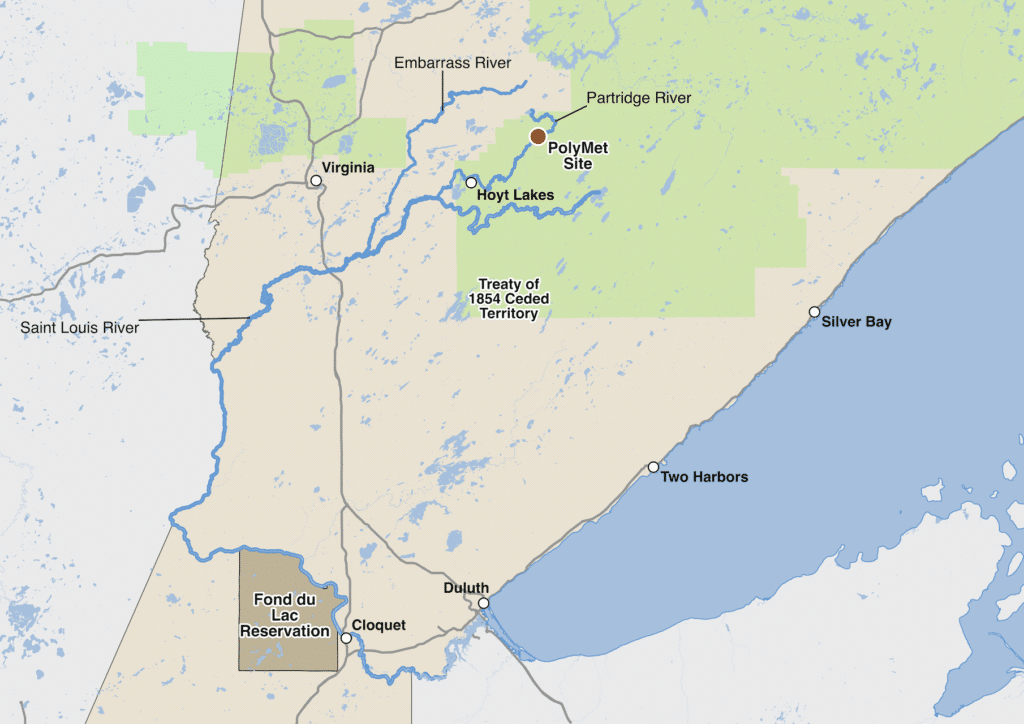

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has revoked a permit for a proposed copper-nickel mine in the headwaters of the St. Louis River. The federal agency says the permit, which would have allowed the owners of the proposed PolyMet mine to destroy about 1,000 acres of wetlands, inappropriately allowed for downstream degradation of waters on the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa’s reservation.

The Fond du Lac Band had previously objected to the permit, supported by the Environmental Protection Agency. The Army Corps’ suspended the permit in 2021. It examined the issues and held a public comment period and hearings a year ago. More than 22,000 people submitted comments on the issue. The EPA recommended the Corps not reissue the permit.

“The Corps acknowledges that EPA and the Band have [Clean Water Act] authority on water quality matters concerning the Band’s Reservation,” wrote Col. Eric Swenson, district commander of the Corps of Engineers’ St. Paul office. “Accordingly, the Corps has determined that, given the Corps’ jurisdiction under CWA Section 404, the Band and EPA’s water quality authorities, and the absence of any necessary permit conditions to ensure compliance with the applicable downstream water quality requirements of the Band … the Corps cannot reissue or modify the suspended permit.”

The decision marks a major obstacle to PolyMet’s proposed mine. The company will need to start over and file a new permit application if it wishes to proceed.

Treaty obligations

The band, the EPA, and many others said there is no way to modify the existing permit to bring the project into compliance with the Clean Water Act. The Corps also noted that not even PolyMet had suggested any new permit conditions to address the Band’s concerns during the public process.

“The Band must be treated as an expert on its own water quality standards,” said Fond du Lac tribal chairman Kevin Dupuis, Sr. at one of last year’s hearings. “Throughout the presentations our experts have been clear and there are no permit conditions that can be applied or be placed on the 404 permit that would ensure compliance with the Band’s downstream water quality standards.”

The Fond du Lac Band celebrated the decision as a win for clean water, wildlife, cultural values, and treaty rights. Tribal leaders pointed out that its waters have long been contaminated by activities like mining, and there is no justification for adding new sources of pollution when prior problems still exist.

“Through the 1854 Treaty the United States government promised us that our Reservation which is located downstream from the Project would provide a permanent homeland for our people forever,” said Dupuis. “We were also promised the ability to exercise our traditional hunting, fishing and gathering rights within our aboriginal lands that were ceded under the 1854 Treaty where the Project will be located. Despite these solemn promise by the United States, our Reservation and our Ceded Territory lands have been under attack from pollution for decades. Today’s decision protects the rights and resources promised to us under the Treaty.”

Tribal water standards

A key issue is the amount of sulfate and mercury in the Band’s waters. Sulfate can hurt the growth of manoomin, or wild rice, and mercury contaminates fish, making them unsafe to eat. Together, the contaminants threaten important food sources and cultural resources.

Because of this, the Band has developed its own water quality standards in recent decades. Nancy Schuldt told the Army Corps of Engineers at one of its hearings in 2022 that she was hired in 1997 to help develop the standards. She said fewer than 50 tribes in the United States, out of more than 570, have developed such legal protections.

“We have established numeric and narrative criteria both that are intended to protect our water resources so that they can continue to support and provide the kinds of resources that our community relies upon for subsistence,” Schuldt said. “So it isn’t just about a basement level of protection. It’s about protecting the qualities and the condition that allow for diversity, for healthy, highly functional ecosystems.”

The Corps also agreed repeatedly with the Band, the EPA, and other comments that pointed out numerous problems with a new mine located in such water-rich environment. Extensive wetlands can cause complex chemical reactions, rising and falling river flows create a dry-wet cycle in riparian areas that exacerbates pollution problems, and more.

Exacerbating pre-existing problems

PolyMet’s primary argument was that its project would actually reduce the amount of mercury, sulfate, and other substances flowing into the St. Louis River. The Band and others disagreed, saying the company did not address the real problem.

“I would just like to say that generally we never made the argument or the contention that it was the sulfate loading or the mercury loading from the project that were the real issue with regards to compliance with our water quality standard. That was not the primary problem,” Schuldt said on the second day of the hearing. “But that’s what PolyMet focused on today in their presentation. Really, it is all about this massive wetland destruction and disturbance to the watershed and the profound hydrologic changes that we’ve described that will contribute to or exacerbate existing exceedances impairments, exceedances of our water quality standards.”

Rep. Pete Stauber, the Republican who represents the area of the proposed PolyMet mine, blamed President Joe Biden and the tribes for the Army Corps’ action.

“Today’s political decision highlights the need for serious permitting reform to limit frivolous lawsuits and modernize the Clean Water Act permitting process,” Stauber said. “I will continue to lead in this fight for this project and many others and to ensure my constituents’ bright future becomes a reality for northern Minnesota.”

PolyMet is not affected by the recent Biden administration decision to block mining on federal lands upstream of the Boundary Waters. PolyMet’s proposed mine would drain south toward the St. Louis River and Lake Superior, rather than northwest to Rainy Lake.

More information:

- NewRange Copper Nickel, LLC – Section 404 permit status – U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- +Army Corps revokes key Northmet copper-nickel mine permit – Duluth News Tribune