National Parks in the Quetico Superior region could see new species nesting there, while other birds disappear in the decades ahead. That’s the result of climate change forecasts from Audubon and the National Park Service.

In a study published last month in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS ONE, ornithologists and climatologists studied global warming forecasts and anticipated impacts on bird habitat.

They found that we could see significant changes in bird ranges soon, if carbon emissions continue at their current rate. As the habitat for many species shifts north, some southern species will start frequenting canoe country, while boreal birds will retreat farther into Canada.

About 26 new species could “colonize” Voyageurs National Park in winter, and 32 at Isle Royale. In the summer breeding season, 37 species may no longer nest at Voyageurs, and Isle Royale might lose 25 species.

Everything from Canada Warblers, Hermit Thrushes, and Red-breasted Nuthatches to the region’s iconic loons are expected to start flying over the Border Lakes in the spring, seeking colder clearer water in Alberta and beyond.

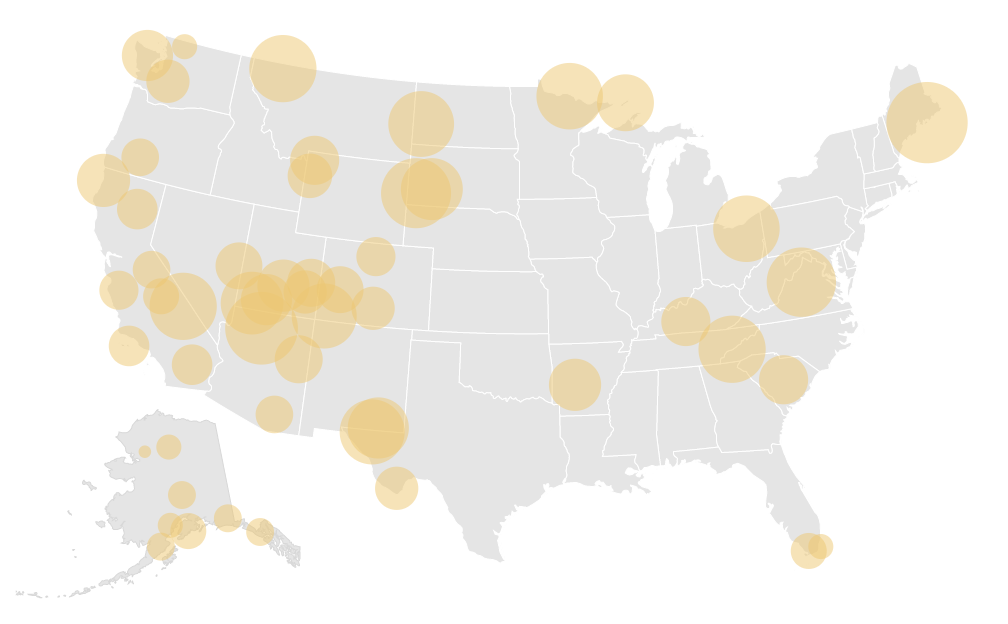

Nationwide impacts and implications

At National Parks across the country, an average of 25 percent of the birds are expected to be different in three decades.

“With new birds coming in and familiar birds heading out, the stewards of America’s public lands will need to prepare for substantial changes in the near future,” said Gregor Schuurman, National Park Service ecologist and the study’s co-author.

Strategies could look like the recent announcement that the National Park Service will reintroduce wolves on Isle Royale.

As National Parks Traveler points out, the wolf effort is intended to manage the moose population and restore balance with impacts on vegetation, the agency is prepared to be “hands on” to respond to climate change. (Fewer ice bridges in winter have prevented mainland wolves from replenishing the park’s population.)

‘High turnover’

At Isle Royale and Voyageurs, the changes are expected to be near the national averages, if not above. If carbon emissions continue at their current elevated rate, both parks would have “high turnover.”

“Parks anticipating high turnover can focus on actions that increase species’ ability to respond to environmental change, such as increasing the amount of potential habitat, working with cooperating agencies and landowners to improve habitat connectivity for birds across boundaries, managing the disturbance regime, and possibly more intensive management actions,” says Audubon. “Furthermore, park managers have an opportunity to focus on supporting the 9 species that are highly sensitive to climate change across their range but for which the park is a potential refuge.”

Certain species that are especially sensitive to climate change may find refuge at National Parks, too. Nine kinds of birds may seek out their habitat at Isle Royale, while four might find it at Voyageurs.

One very special species at risk in both parks is the loon. Conditions for the black-and-white waterfowl are expected to “worsen” in Voyageurs National Park, while Isle Royale might lose them altogether.

The climate is on track to push loon habitat farther north. Their haunting call in summertime, claiming a lake, reaching far across the water, could be lost in the amount of time since Brule Lake in the Boundary Waters was closed to motors in 1986.

The loon’s shifting summer range

Interconnected ecosystems

Birds aren’t just pretty to see and hear, but critical parts of the food web and the ecosystem. A large change in what birds live where could cause other changes in seed distribution and a multitude of other ways birds can affect their habitat.

“On average, we’re talking about a large amount of change. One-quarter of the birds found in each of these parks, on average, is going to be a different bird in the future,” Dr. Chad Wilsey, director of conservation science for the National Audubon Society, told National Parks Traveler. “This is going to have ecological cascading effects and the potential to impact not just the birds themselves, but the ecosystems that may be influenced by them.”

Not every change in bird species the researchers forecast will come true, of course. They only predicted how habitat might change and how birds could respond to those changes. Some species might be able to adapt.

The scientists stressed it’s also not inevitable. There is still time to slow global warming, and if humans reduce emissions, many National Parks could hold onto bird species closely connected to the ecosystem.

“It’s more important than ever to get on the path to clean energy solutions as we get a clearer picture of how our changing climate will impact birds and the places they need,” said Matthew Anderson, vice president of Audubon’s Climate Initiative.

Resources:

- The Future of Birds in Our National Parks, Audubon

- Birds And Climate Change: Study Predicts Upheaval In National Park Bird Species, Kurt Repanshek, National Parks Traveler

- Birds and Climate Change: Voyageurs National Park Brief (PDF), Audubon

- Birds and Climate Change: Isle Royale National Park Brief (PDF), Audubon

Reference:

- Wu JX, Wilsey CB, Taylor L, Schuurman GW (2018) Projected avifaunal responses to climate change across the U.S. National Park System. PLoS ONE 13(3): e0190557. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190557