At the end of July, Voyageurs National Park reopened the last campsites and other areas that had been closed since bald eagle nesting season began. Prohibiting visitors within 200 yards of known nest sites is meant to help prevent the big birds from abandoning eggs or chicks in the nest when spooked.

The National Park Service has been careful to protect bald eagles in Voyageurs National Park for decades. The park was created at almost the same time as the Endangered Species Act became law, and the recovery of America’s national bird is seen as one if its proudest successes.

There were only six nesting pairs in Voyageurs in 1975, and those birds fledged just one chick (the pesticide DDT weakens eggs and increases failure). As part of protecting the species as specified by federal law, Voyageurs has closed areas near known bald eagle nests for much of spring and summer since 1992.

The effort has been successful, and Park Service biologists counted at least 27 nests in the park that hatched at least one chick this year. In 2009, there were 39 breeding pairs and 38 fledglings, and 42 breeding pairs and 37 fledglings in 2015.

The bald eagle was removed from the list of Endangered Species in 2007, though it remains protected by federal law.

Now, research shows that the bald eagle comeback at Voyageurs may have reduced the number of two other fish-loving birds, the osprey and great blue heron. With similar preferences for nesting, perching, and hunting as herons and osprey, eagles are fierce defenders of their own nests and territories.

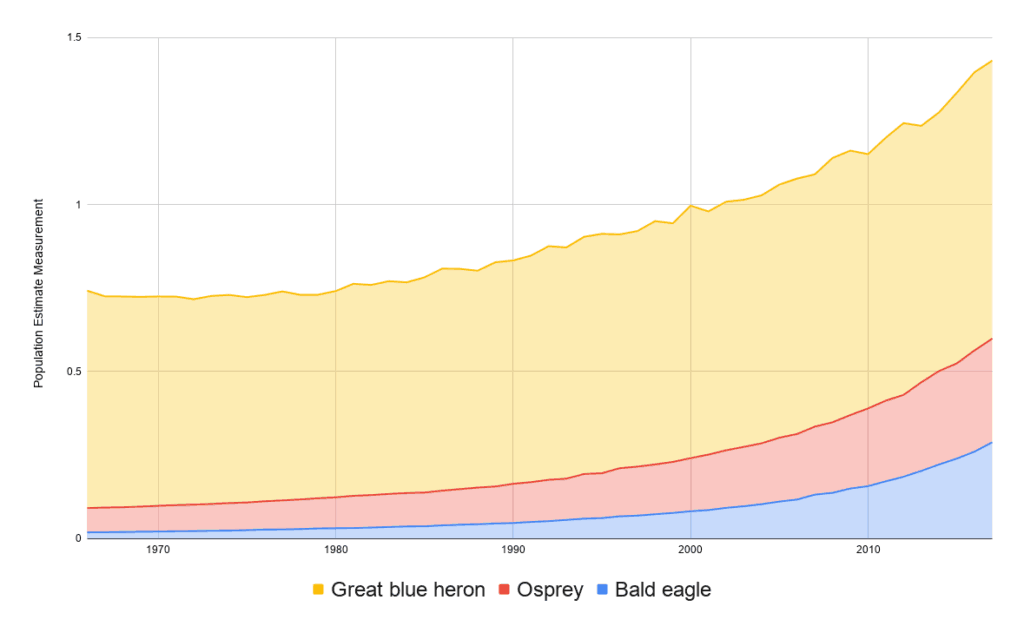

All three bird species have increased in numbers across the United States since the 1960s, after DDT was banned, but it’s been a different story at Voyageurs.

“[A]fter more than a decade of successful joint recovery, osprey and great blue heron populations declined and became nearly extirpated from the park. Conversely, bald eagle populations increased steadily for over three decades with the help of intensive management efforts,” the authors wrote.

The scientists also looked at factors affecting bird populations like fish availability and climate change, but did not find an explanation for osprey and heron declines greater than the return of bald eagles.

“The strongest most consistent predictors that we found associated with the decline in osprey and great blue herons was abundance of bald eagles in the park at breeding season,” Jennyffer Cruz, a postdoctoral researcher in ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and lead author of the study, told The Wildlife Society.

The scientists say it points to how the complex connections between all living things can complicate attempts to restore populations.

“Returning top predators, like eagles, to their former habitats, are true conservation success stories, but their potential to restore ecosystems is not guaranteed,” they conclude.

Visitors wishing to see bald eagles at Voyageurs have a good chance just by keeping an eye on the sky and tall pines. The highest density of nests are found on the shorelines and islands of West Rainy, North and East Kabetogama, and West Namakan Lakes.

More information:

- Bald eagle recovery hinders osprey, heron populations, The Wildlife Society, July 2, 2019

- Bald Eagle Nesting Areas Reopened for 2019 in Voyageurs National Park

- Bald Eagle information, Voyageurs National Park

References:

Cruz, J, Windels, SK, Thogmartin, WE, et al. Top‐down effects of repatriating bald eagles hinder jointly recovering competitors. J Anim Ecol. 2019; 88: 1054– 1065. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12990