New research shows how the hunting habits of wolves affects the water cycle in Voyageurs National Park.

Beavers are ‘landscape engineers’ and a vital part of wetland, river, creek and pond landscapes. And for wolves in northern Minnesota, beavers are a food resource. This led the Voyageurs Wolf Project to ask: do wolves change a wetland ecosystem by preying on beaver populations?

The concept of wolves having landscape-scale impacts gained attention several years ago in a viral video about Yellowstone National Park. There, scientists said reintroduced wolves had reduced the elk population so much that it allowed more willows to grow along the park’s famed trout rivers, reducing erosion. This “trophic cascade” has been hotly debated in scientific circles ever since.

Scientists who have been using GPS collars to track wolves in the Voyageurs ecosystem on the Minnesota-Ontario border for five years, provide compelling new evidence of how the predators alter water flows. Their findings are published in Science Advances.

The ongoing research project has published other noteworthy studies, including video documentation of wolves preying on fish, and the important role of blueberries in wolf diets during late summer.

“How large predators impact ecosystems has been a matter of interest among scientists and the public for decades,” said Tom Gable, the study’s lead author. “Because wolves are the apex predators in northern Minnesota and beavers are ecosystem engineers, we knew there was potential for wolves to affect ecosystems by killing beavers.”

The scientists say this study was inspired by an observation while they were visiting one of the thousands of sites where a GPS collar indicated a wolf had spent time. Staying in one place often indicated a kill site, and by visiting the sites shortly afterwards, the scientists were discovering a lot about wolves’ connections to the ecosystem. They’ve bushwhacked to nearly 12,000 such sites so far.

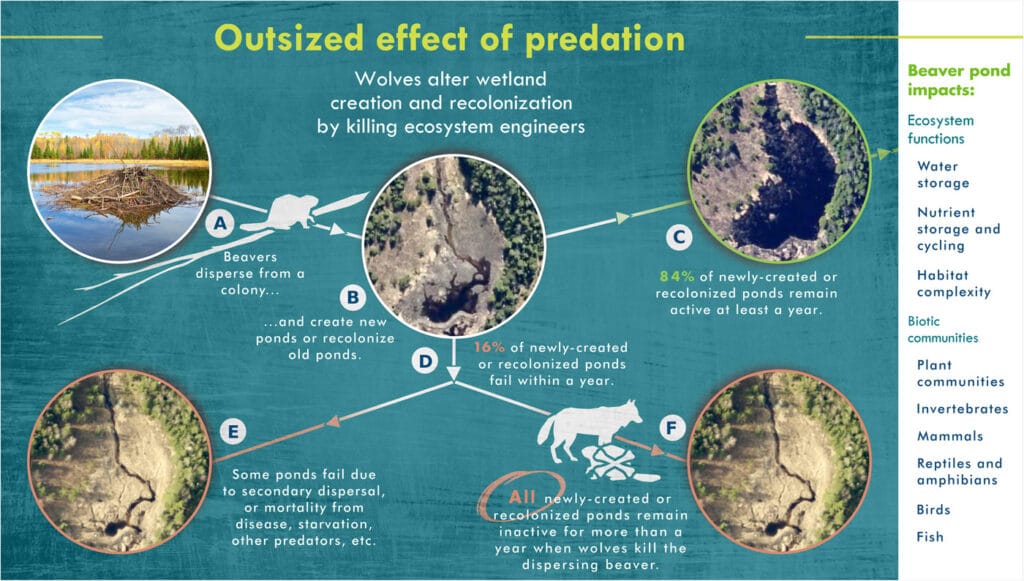

Early in the study, the scientists observed where a wolf killed a beaver that had just started building a new pond. Once the beaver was dead, the dam quickly blew out, and the pond drained. Five years later, the pond has still not been reestablished.

“This initial observation was fascinating and we realized we needed to figure out how wolves were connected to wetland creation in the Greater Voyageurs Ecosystem,” said biologist Austin Homkes.

The essence of the answer is that the wolves prey on many young beavers, who are forced to leave home territories and find their own home. These dispersing beavers usually take over an abandoned dam pond, or get to work on their own. But wolves prevent many from succeeding. The young beavers must venture on land for food and building materials, where they are killed by the wolves.

The researchers found that none of these ponds were occupied by another beaver for at least the next year, and possibly longer. Abandoned ponds continued to dry out and get covered in grasses and shrubs, while new dams failed and no pond was created.

“Because dispersing beavers are primarily solitary individuals, the only way for a newly created or recolonized pond to persist once a wolf kills a dispersing individual is if another dispersing beaver reaches that pond and continues to maintain the dam. Our work suggests that such a scenario is rare and that once a wolf kills a dispersing individual, that newly created or recolonized pond remains unoccupied for the rest of that year. Furthermore, our data suggest that the ecological effects caused by wolves disrupting beaver-mediated wetland creation might last for several years, but longer-term research is needed to assess the duration of effects.”

One key point is that the wolf predation on dispersing beavers does not have a significant impact on the beaver population or its distribution through the area. But it does affect the movement of water.

Wolves tracked by the scientists affected the establishment of nearly 90 ponds each year, having a significant effect on the ecosystem. Beaver ponds provide valuable habitat for moose, birds, reptiles and many other types of wildlife, and hold back water, removing nutrients, and more.

As a top predator and a critical boreal ecosystem engineer, the relationship between wolves and beavers has a broad impact on the landscape. The Voyageurs Wolf Project has now added another piece to this complicated network of animals, plants, and waterways.

More information:

Gable, Thomas D., Sean M. Johnson-Bice, Austin T. Homkes, Steve K. Windels, and Joseph K. Bump. “Outsized Effect of Predation: Wolves Alter Wetland Creation and Recolonization by Killing Ecosystem Engineers.” Science Advances 6, no. 46 (November 1, 2020): eabc5439. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc5439.

- Voyageurs Wolf Project

- Wolves preying on beavers in Minnesota reshape wetlands – Associated Press

- Wolf attacks on beavers are altering the very landscape of a national park – Science

- Study shows Yellowstone wolves’ impact on streams – The Wildlife Society