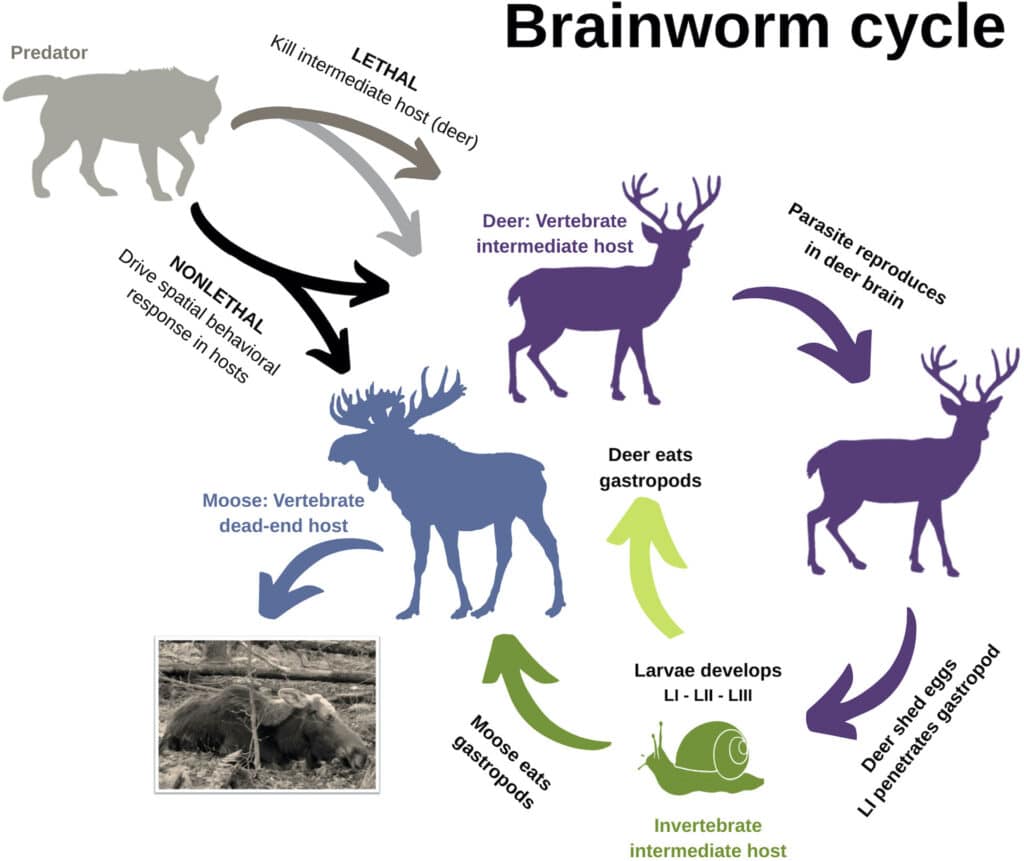

Research conducted on and around the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indian Reservation has shown how the presence of wolves can help reduce risks to moose. The iconic herbivores have seen their numbers cut in half in northern Minnesota in the last decade, with one reason being brainworms transmitted by whitetail deer.

The brainworms are harmless to the deer, but often fatal to moose. Scientists report that 23 percent of collared moose studied in northern Minnesota died as a result of the parasite in recent years.

The study, conducted by the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Sciences and the Grand Portage Band, analyzed data from 94 adult moose, 89 deer, and 47 wolves between 2007 and 2019. It was published in the peer-reviewed journal, Science Advances.

Are wolves bad for moose populations?

“We often think of wolves as bad news for moose because they kill a lot of calves,” said principal investigator Tiffany Wolf, DVM, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Veterinary Population Medicine. “But this suggests that wolves may provide a protective benefit to adult moose from a parasite-transmission perspective. Because brainworm is such an important cause of adult moose mortality in Minnesota, we can now see that the impact of wolves on moose is a bit more nuanced.”

By tracking the wolves, moose, and deer, the scientists were able to see seasonal behavior, and how wolves help reduce transmission of the brainworm from deer to moose.

Staying at a safe distance

Wolves affect the transmission of the brain parasite in two ways: by preying on deer, and by affecting the seasonal movements of moose and deer.

“Under minimum wolf predation risk during winter, deer selected only coniferous forests (the reference class), used deciduous forest according to availability, and further selected lower elevations,” the study reported. “Moose showed small increases in selection for open areas and highlands. In general, the observed selection of covertypes in winter persisted during spring migration and summer, except for elevation.”

But, when wolf populations grew and the risk of predation increased, both deer and moose altered their behavior. The end effect was they chose different types of habitat to avoid wolves, thereby keeping the two prey species farther apart, and reducing the transmission of brainworms.

“Deer and moose shifted habitat selection in response to wolf pressure, becoming more similar in cover type but different in elevation,” the authors wrote. “The differences in selection were primarily a result of selection changes by deer.”

Notably, the authors saw the most drastic separation during the warm season months, when the invertebrates that transmit brainworm are present. They also noted that wolves are the primary predator of deer, and by preying on the animals, wolves reduce their population size and thus the risk of brainworm transmission to moose.

The research findings are hoped to give state and tribal managers a better picture of the ecosystem as they develop wildlife management plans. The authors say it could lead to greater deer hunting opportunities, and management methods that would also help with threats to deer like chronic wasting disease.

The Grand Portage Band has prioritized protecting the moose population as an important subsistence and cultural resource. The new findings provided some hope that strategies can be developed that will help.

“I think if we can agree on an area in the core moose range where we are going to work to benefit moose, and we include deer management and maybe some wolf management to start, along with targeted habitat work, we might succeed,” study author Seth Moore, a wildlife biologist at the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, told the Pioneer Press. “We might be able to keep moose in Minnesota.”

More information:

- Research brief: Wolves might help moose avoid acquiring a deadly deer parasite – University of Minnesota

- Spatial compartmentalization: A nonlethal predator mechanism to reduce parasite transmission between prey species – Science Advances

- Wolves Keep Brain Worm–Spreading Deer Away From Moose Populations in Minnesota – Smithsonian

- Wolves may help keep deer — and brainworm — away from moose, MN study finds – Duluth News Tribune