By Alissa Johnson

When I was in high school—the mid-1990s—a debate arose over motorboat access to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW). I went to a demonstration to keep motors out; it was a spring or summer day, and I remember the way the sun sparkled on Como Lake in St. Paul. I met Arctic explorer Ann Bancroft, and for the first time, I glimpsed the Boundary Waters as a political landscape. Until then, I knew it as the place I learned to paddle a canoe in a straight line, where at the age of 12, I took my first shaky steps with my dad’s wooden Chestnut on my shoulders. I’d never had the desire to leave a motorized wake across its lakes, and the idea of such a debate had never occurred to me.

It would take until my late 20s to fully grasp the region’s history as a political hotbed—a stage for a national debate about land use. On one of my first assignments for Wilderness News, I drove to Ely and met with Bill Rom. Rom had been named Canoe King of Ely by Argosy Magazine during the 1960s; he’d spent his life outfitting canoeists and championing the preservation of wilderness. But no one knew if he would speak to me. He was nearing 90, and his interest in recalling the past was unpredictable. I sat down in the dining room with his daughter and his wife, a pot of tea between us. Rom listened from his chair in the living room, and then, he made his way to the table. He was sharp and energetic, and for two hours, he gave me a true understanding of the passion behind the wilderness debate. During the 1970s, a time of struggle for the local economy, his vocal support of wilderness led locals—his own neighbors—to blockade his business. Their signs read, “Run the Bum Rom Out of Town.”

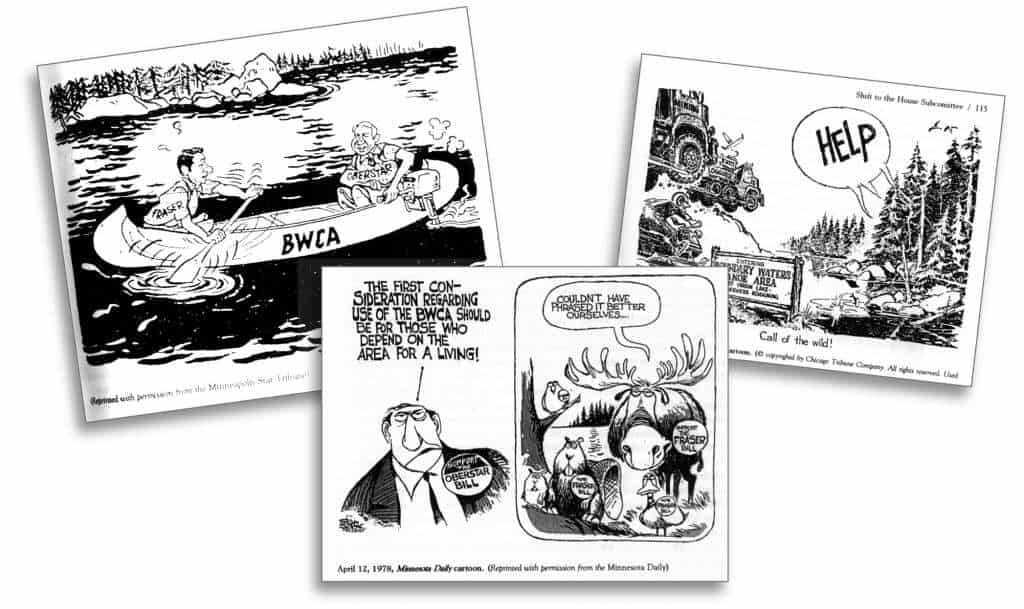

The passion grew out of a century-old debate over land management often invisible to today’s Boundary Waters visitors: national and public interests conflicted with local desires, resulting in fiery debates and feelings of helplessness. Over the years, Sigurd Olson was burned in effigy and at one point, the whole town of Ely was blockaded. The perception that political decisions were made in secret, in the middle of the night, didn’t help. During the 1960s, as the Wilderness Act of 1964 was signed into law, one Wilderness News reader called the debate Minnesota’s “wilderness problem.”

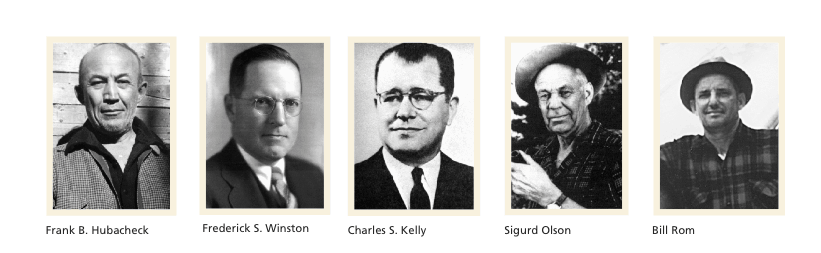

It was from this wilderness problem that the Quetico Superior Foundation emerged. In 1947, the very men who convinced Ernest Oberholtzer to lead the charge against the damming of the Quetico Superior region (see page 7), Charles S. Kelly, Frank B. Hubacheck and Frederick S. Winston envisioned an organization that advanced science and education in the region. In 1949, President Truman would issue an executive order prohibiting flights over Superior Roadless Area below 4,000 feet, eliminating fly-ins into this wilderness area. Prior to that decision, and in the years that followed, the group provided aid to the many groups influencing the region, including the U.S. Forest Service, the Department of the Interior, and what was then Minnesota’s Conservation Department. They even sponsored a movie about fly-ins into canoe country and funded additional studies to deepen these groups’ understanding of it.

And then, in 1964 the United States Congress passed the Wilderness Act. The bill included the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (BWCA), but not as a true wilderness. Congress declared that the new law could not modify provisions in the Shipstead-Nolan or Thye-Blatnick Acts, which restricted logging near shorelines, alternation of water levels and flights below 4,000 feet. The Acts allowed for some activities like timber harvesting; the BWCA was to be managed as a primitive area without “unnecessary restrictions” on these uses. The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Review Committee was created to figure out what that meant.

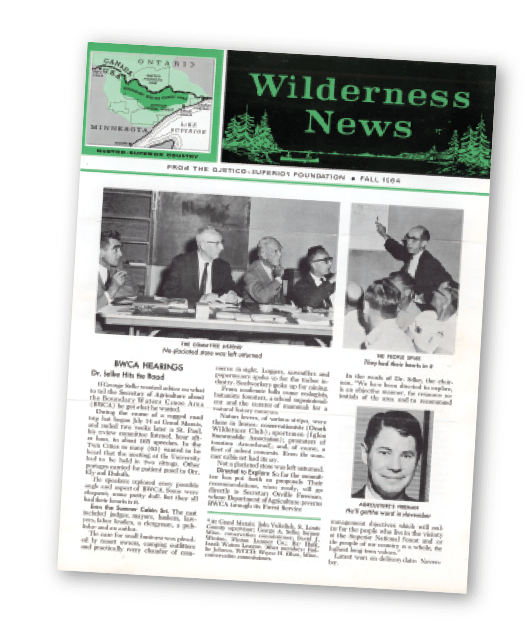

During the same year, the Quetico Superior Foundation started Wilderness News. The reader who coined the phrase “wilderness problem” also asked, “But which side are you on? What are you trying to prove?” Frederick Winston, son of Frederick S. Winston, replied, “The Foundation’s immediate aim is to help this committee expedite its enormous task in any way we can… The only way to arrive at an equitable solution of any problem is first to listen to all facts and all opinions of all sides. This, at least, is what we are trying to prove.”

That sentiment has guided the Foundation ever since. During the 1980s, grants to the Project Environment Foundation aided the development of a management plan for the BWCAW (officially declared a wilderness in 1978). The foundation has given funds to study user demand, to writers preserving the region’s history and to groups connecting kids with wilderness. It has helped purchase land for preservation and helped groups that advance our understanding of the region through experience, science or education. All the while, it has published Wilderness News to catalog and spread the region’s stories—like Bill Rom’s.

Shortly after I wrote about Rom, he passed away. His daughter, Becky Rom, took over the preservation of his story, and I went on to write about other men central to the wilderness debate. But the story of the BWCAW—of wilderness in Minnesota and the people who seek to make a livelihood beside it—continues, as cell phone towers and mining abut its edge. The story is more complex than motors versus no motors, or the simplified understanding of one high school girl. The need for understanding and common ground is as great as it ever was, and it only takes a glance at the Foundation’s grant history to understand the role it seeks to fill.

This article first appeared in Wilderness News Spring 2012