Jack Rajala has spent most of his life in the forest. He is well known in Minnesota forestry circles as an advocate for white pine restoration and as part of Rajala Companies, his family’s business that has logged and milled timber in Itasca County for more than a hundred years. Over the last 25 years he and the company have planted nearly 4,000,000 white pine seedlings on their 35,000 acres. In addition to planting, they have also assiduously cared for each seedling and stand by hand: prepping ground, clearing brush, pruning, and stapling paper caps over each tree’s new buds. In the beginning they made their share of mistakes, Rajala admits, but now, he’s the author of a book on the subject, Bringing Back the White Pine, which explains how to successfully grow these trees despite the obstacles of invasive species, scarce seed sources, and munching deer. As one of the reigning and respected experts on white pine restoration in Minnesota, Wilderness News was pleased to recently pull Rajala out of the woods to find out more about what drives his unflagging devotion to the trees.

A child of the Northwoods, Rajala was born in 1939 in a homesteader’s cabin, in Busticogan Township. He grew up in the Bigfork area and then went away to St. Olaf College, where he studied economics. His family encouraged him to go out and take a good look at the world, so he set off for southern California and started a career in finance and accounting. It wasn’t until his father fell ill in 1962 that he returned to the Northwoods.

Back amongst the towering pines, Jack realized just how rooted he was to the area, and hasn’t left since. He now resides in an old lodge built before the turn of the century, surrounded by 6,000 acres of woodland preserve. As much as possible he shares his time and his home with his five children, four of whom live in the Grand Rapids area, and his eleven grandchildren. He travels to Finland regularly to visit family and to check up on churches he is helping to build in Karelia, the Finnish part of Russia and his family’s ancestral homeland. At 69 years old, he is bustling with energy, though he admits “I don’t go to a lot of meetings and rant and rave like I used to.” He still serves on the Allete/Minnesota Power board of directors, which, he says, “gives me a little outside contact.” More and more, Rajala focuses his energies where he’s always been most passionate: the woods.

In 1965 when Rajala first began to think about planting white pine, he had to fight with the foresters. They’d tried to plant it, they said: it didn’t work. There were too many obstacles, blister rust (an invasive fungus) being the main one. But Rajala looked around the forest and assessed it honestly: if his family’s timber company and others like it continued to harvest white pine there would soon be no more white pine to harvest. Part of the reason public attempts at regenerating had failed was because “[public agencies] function on the short-term: short term budgets, short term timelines, short term positions.” He’s seen that “energy builds behind a certain issue and money gets spent, but then stops. Certain public and legislative initiatives come up, but then they fall off. Most of these things have not been sustained the way they should. The trees are on long term rotation—you can’t just give it five or ten years.” And so it is that he has devoted a huge chunk of his life and his company’s resources to these trees.

Part of what has driven Rajala is his role as a family businessman. “White pine is still the most valuable tree in Minnesota,” he says. White pine was how the Rajala Companies got started and it has continued to be their most profitable species. They have planted millions of seedlings in order to keep the species in existence, but the Rajalas are also developing the program so that, over time, they can sustain their business as well. He’s honest that times aren’t easy for a family owned company: “We’ve had to downsize a lot. We’re constantly trying to find a better business model. But we’re going to duke it out.” He’s pleased his family has been able to build a business that the community is proud of: “I’m proud I’ve been able to see my family stay together, stay close to something, to come back to something, and that most of us have found a great life here.”

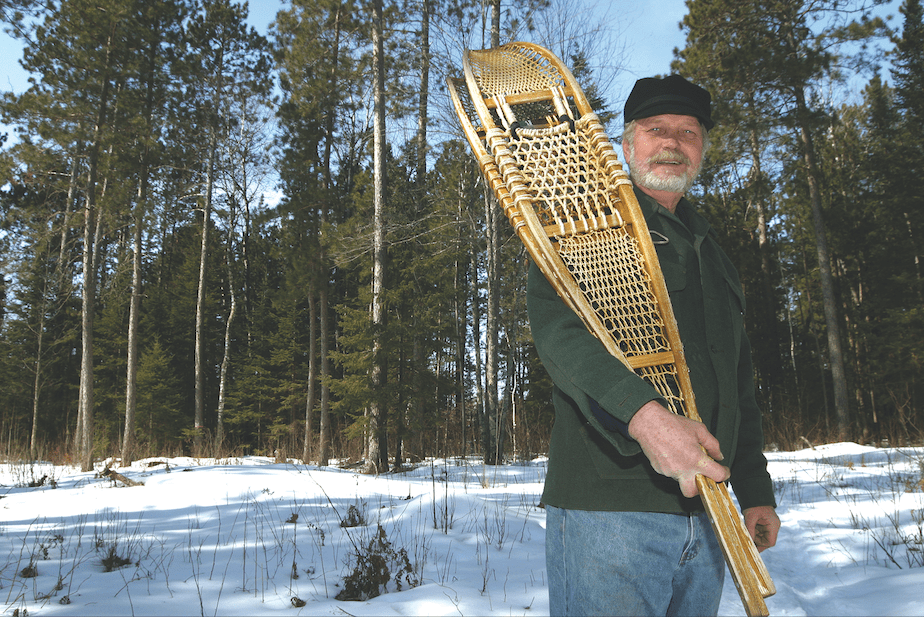

Besides the economic factors, Rajala knows “it’s just a passion for it” that keeps him going. He can’t articulate exactly what it is about the woods and white pine in particular that captivates him, but, he says, “The majesty of them, even when they’re young—that means a lot to me emotionally and spiritually. . . . These trees have a way of responding, almost as if they were looking, saying, ‘we need you, we need you.’” And so he’s there, every day. He is still the company forester and logging superintendent, helping with the hard work of caring for the pines and harvesting them when it’s appropriate. When it comes down to it, Rajala is honest that he’d like to retire soon, “but that just means I’ll spend more time out there with the trees.” It’s hard to imagine him doing more than he does already: by his own admission, “What I’m riding high on right now, are two of the most important inventions humanity ever came across: a canoe and a pair of snowshoes. No one spends more time in a canoe or on snowshoes than I. I use them in both my work and my leisure.” But, like with planting white pine, if it’s possible to be in the woods more, Jack Rajala is certainly the man who will find a way to make it happen.

By Laura Puckett, Wilderness News Contributor

This article appeared in Wilderness News Spring 2008