With the announcement last week that no mining will be allowed on federal lands upstream of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness for 20 years, many canoeists, campers, and advocates celebrated a major milestone that came after more than a decade of effort. While there may still be legal challenges, the protective measure aims to provide two decades in which copper-nickel mining will not affect the beloved wilderness area.

Twenty years for 234,000 acres is not the end goal, though. Other mine proposals are still in the works outside the newly protected area, and numerous efforts are underway to protect the waters of northeastern Minnesota.

PolyMet plus

The new mining ban in the Boundary Waters watershed does not affect the proposed PolyMet copper-nickel mine, which is in the Lake Superior watershed. The project is the furthest along in the review and regulatory phase of any such mines in Minnesota, but is being held up by several significant lawsuits.

But PolyMet has its own problems. Last November, the Minnesota Supreme Court heard a lawsuit by environmental groups and the Fond Du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa to the project’s water quality permit. The groups say the permit issued by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) should have included strict limits for pollutant discharges like mercury and sulfate. Their lawyers have also argued the MPCA illegally suppressed comments about the mine’s permit from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Permit problems have not deterred PolyMet, though. Today, the company announced it has completed a new corporate partnership with the corporation that controls a neighboring ore deposit.

“The successful completion of this transaction is expected to more than double the resources attributable to PolyMet shareholders,” said PolyMet CEO John Cherry when the deal was announced last year. “It also introduces a new member to the NorthMet Project with a strong balance sheet, an exceptional record of community involvement and sustainable mining practices, and world-class technical and mining capabilities.”

Permanent potential

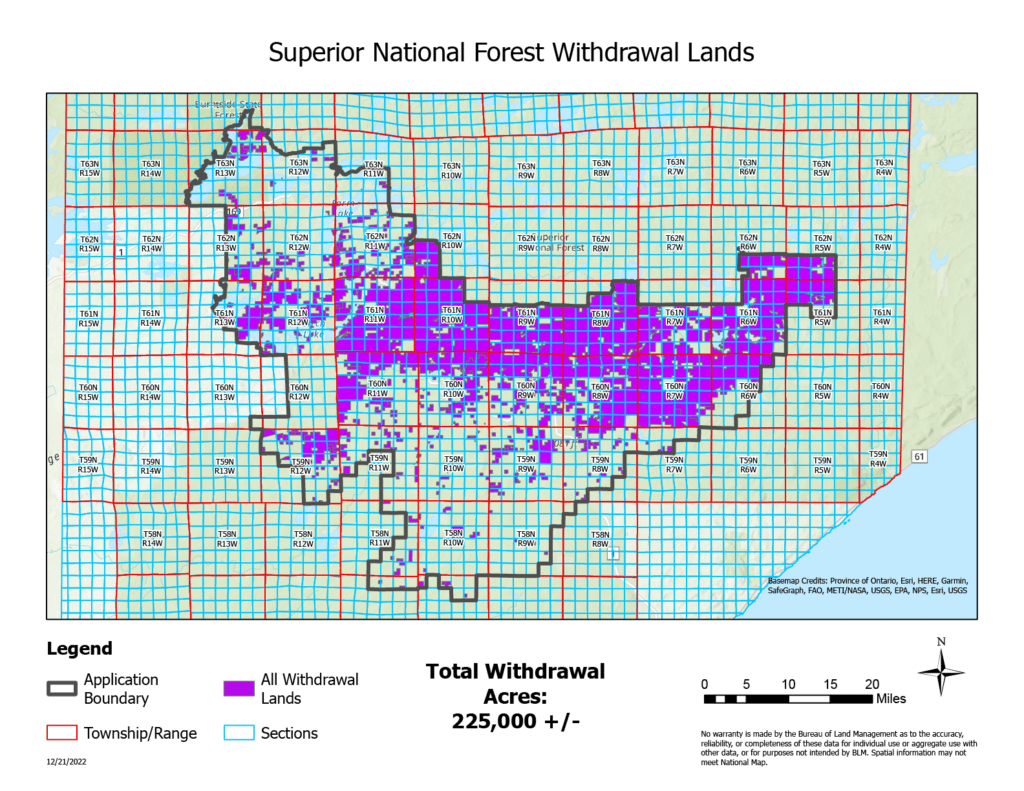

Federal law allows the executive branch to withdraw publicly-owned minerals from leasing for up to 20 years. That is what Interior Secretary Deb Haaland did last week with the ban announcement. But 20 years can go fast — it’s been about 15 years already since the corporate ancestors of Twin Metals first started developing a mine proposal near Birch Lake. It’s been 57 years since the first leases were issued for minerals in the area.

The only way to permanently prohibit mining in the area is an act of Congress. Only the legislative branch can enact mining bans without an expiration date.

To that end, Rep. Betty McCollum has introduced bills for several years that would enact such a permanent ban. Five days after Secretary Haaland announced the 20-year ban, McCollum reintroduced legislation to make it permanent (HF 688).

“Last week’s historic action by Secretary Deb Haaland to officially withdraw more than 225,000 acres of federal lands and waters from mineral leasing is huge and welcome news, ensuring the pristine Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness will remain intact and protected for 20 years,” McCollum said. “However, more work remains: these protections must be made permanent – which is why I’m reintroducing the Boundary Waters Wilderness Protection and Pollution Prevention Act for this Congress.”

The legislation was passed out of its first committee last year but never got a vote on the House floor. With the House of Representatives now in Republican control, prospects for the legislation advancing are slim, with Eighth District Republican Pete Stauber a staunch opponent of environmental regulations.

Twin Metals leases

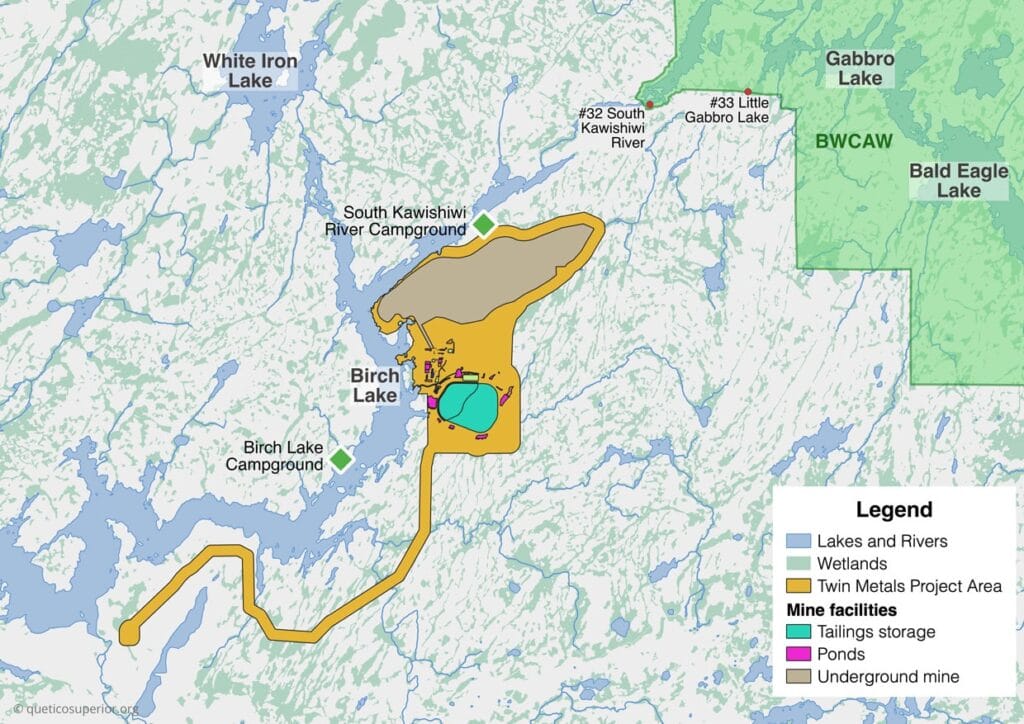

The ban on mining in the watershed of the Boundary Waters that was announced on Jan. 26, 2023 was basically a death blow for the proposed Twin Metals project. But, there is still a small chance the project could proceed.

Twin Metals, owned by Chilean conglomerate Antofagasta PLC, has developed its mine proposal based on leases to extract publicly-owned minerals that were first issued to other companies in 1966. The leases were transferred and sold over the years, despite the fact they were intended to promote mining in the short-term after they were first issued. Twin Metals was the latest in a long line of lease holders.

Since late 2016, the leases have been cancelled, renewed, and cancelled again. If Twin Metals still held the leases now, they would potentially be “grandfathered in,” allowing the company to extract minerals despite the wider watershed ban.

But, in January 2022, the Biden administration upheld an Obama decision to reject renewal of the leases. Twin Metals no longer has control of the leases, and thus no chance of getting an exemption from the ban. But, last August, the company sued the federal government to force renewal of the leases. If they were to prevail in court, it’s possible they could use the reinstated leases to operate. But the company has also said it planned on acquiring other leases from the federal government to fully realize its mine plan.

Minnesota ban

There might be a slightly smoother path for a mining ban at the Minnesota legislative level. The state can also take actions to prohibit issuing mineral leases for lands upstream of the Boundary Waters, although Minnesota owns significantly less mineral rights in the region than the federal government.

In January, Minnesota legislators introduced a bill to permanently prohibit mines in the wilderness watershed (HF 329/SF 167). Unlike Congress, the legislators sponsoring the bill are from the same party, Democratic-Farmer-Labor, that controls all three branches of state government.

“The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is recognized the world over for its pristine waters, unique ecosystems and stunning beauty,” said Senate author Sen. Kelly Morrison. “Let’s permanently protect this watery wilderness before it’s too late and we’ve lost it forever.”

Other state-level strategies

Several proposals have been introduced at the Minnesota legislature to add pollution protections from copper-nickel mines. A ban around the Boundary Waters has never been the sole goal for several advocacy groups. PolyMet, Teck, and other companies are attempting to open mines in areas outside the Boundary Waters watershed, including the headwaters of the St. Louis River.

On Feb. 2, eight DFL legislators sought to resolve what has long been considered a conflict-of-interest for state regulators the Department of Natural Resources. The agency is currently required by law to promote mining in the state, but is also in charge of conserving lands and waters. The bill (HF 1225) would transfer the responsibility to promote mining to another state agency, the Department of Employment and Economic Development, leaving the DNR to focus on its conservation mission.

On Monday, two bills to tighten regulations were introduced. One would prohibit “bad actors” from getting permits to mine in Minnesota, and the other would require proof a mine can prevent pollution before permits are issued.

The “No Bad Actors” bill (HF 1619) would keep companies that have violated environmental, labor, corruption, or other laws in the past 15 years from being allowed to mine in Minnesota. Glencore, the global conglomerate that owns most of the proposed PolyMet mine, may be an example of one such applicant. The company pleaded guilty last year to engaging in bribery and price manipulation.

“Glencore paid bribes to secure oil contracts. Glencore paid bribes to avoid government audits,” said U.S. Attorney Damian Williams for the Southern District of New York. “Glencore bribed judges to make lawsuits disappear. At bottom, Glencore paid bribes to make money – hundreds of millions of dollars. And it did so with the approval, and even encouragement, of its top executives.”

“Prove-it-first” has been introduced each of the last few legislative sessions, without passing. It was introduced today, Feb. 13, with 22 co-authors in the House of Representatives. (HF 1618) With the DFL in control of the state government, its prospects should be better than ever.

One of the first regulation ideas suggested in the state more than a decade ago was to copy Wisconsin’s law called “prove-it-first.” The Badger State had this regulation in place from 1998 to 2017, requiring any company applying for a new sulfide ore mining permit to have an example of a similar mine elsewhere that had operated for 10 years, and been closed for 10 years, without polluting. No mining company attempted to meet that standard while it was in effect.

Expediting environmental review

Rep. Pete Stauber, the third-term Republican who represents northeastern Minnesota, has objected to most of the mining actions by his Democratic colleagues in Congress and the president. He has also taken several steps to support mine proposals in the House of Representatives.

The first legislation Stauber introduced this year was to speed up the environmental review and permitting process for mining in the United States. It would place time limits on review, limit litigation, and change how federal agencies work on proposals together.

“Our country, including my northern Minnesota district, is blessed with vast mineral wealth that should supply many of our needs,” said Stauber. “Unfortunately, our current permitting process fails to deliver our resources because it is far too often abused by keep-it-in-the-ground activists who oppose mining solely on ideological grounds.”

The legislation is supported by several large industry groups, including the National Mining Association. Minnesota’s other Repblican representatives are also co-sponsors, including Reps. Emmer, Fischbach, and Finstad. It has not yet received any hearings or other actions in Congress.

The road ahead

A common argument heard over recent decades has been that upstream of the Boundary Waters is simply not the right place for copper-nickel mining. The recent ban announced by the Biden administration is the biggest step yet toward putting that in policy. But the prospect of such mining in watery northern Minnesota is not eliminated.

Numerous deposits of ore, and mine possibilities, remain in the region. They represent economic development and taxes and a risk to of polluting priceless lakes, rivers, and aquifers.

As long as that’s true, the portages of wilderness protection will be crooked and winding (paraphrasing Edward Abbey).