In many ways, the climate change discussion is everywhere. Paris hosted the 2015 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In March of this year, President Obama announced a pact with Canada to fight climate change. The U.S. Department of Justice announced that it was considering whether to prosecute climate deniers. Yet on a personal level, the scale of the issue can make it hard to navigate. How will it affect the places you love? What can you do to have an impact on the situation?

In this series, Wilderness News dives into the topic as it relates to northern Minnesota and the Quetico Superior Region. We’ll learn what climate change means for places like the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and north woods communities. We’ll also meet people and organizations working toward solutions. We start with Climate Generation: A Will Steger Legacy, an organization founded by Ely resident and Polar explorer Will Steger; it’s reimagining the way we talk about climate change across Minnesota, including places like the Iron Range.

From explorer to advocate

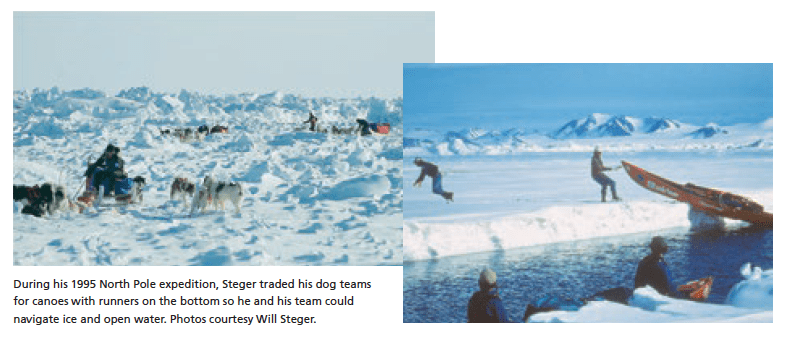

Polar explorer Will Steger has spent over 1,000 days of his life on the ice of the Arctic Ocean. He made a name for himself by traveling to the North Pole by dogsled in 1986—the first confirmed such trip to the Pole followed by the longest, unsupported dogsled expedition across Greenland in 1988. He returned in 1995, approaching the Pole from the Russian side. While the ice in the Arctic Ocean is always shifting, in 1995 he encountered expanses of water so wide he couldn’t see across them. On the Canadian side, he and his fellow explorers traded dogs for canoes with runners that allowed them to move over ice and water. The region’s transformation was stark; this type of open water had never existed in the North Pole. In 2002, sitting in his Ely, Minnesota home, Steger read that a segment of the Antarctic Larsen Ice Shelf had disintegrated—an expanse of ice 300 miles across that he once took 30 days to navigate.

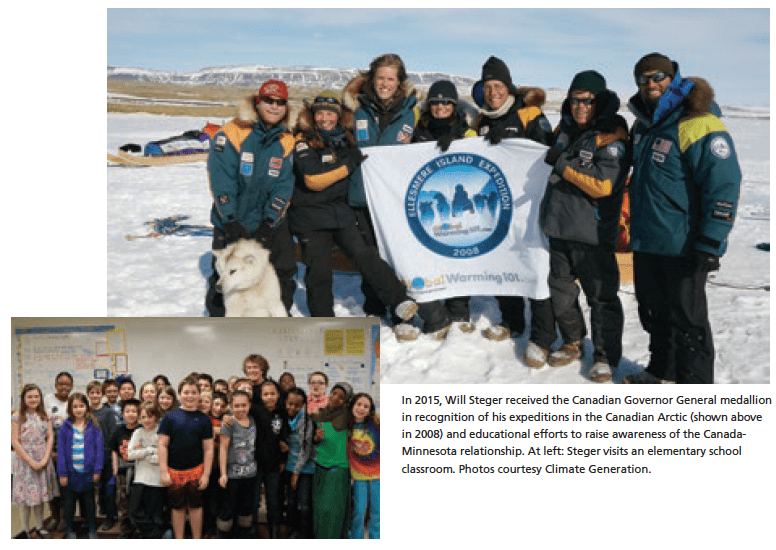

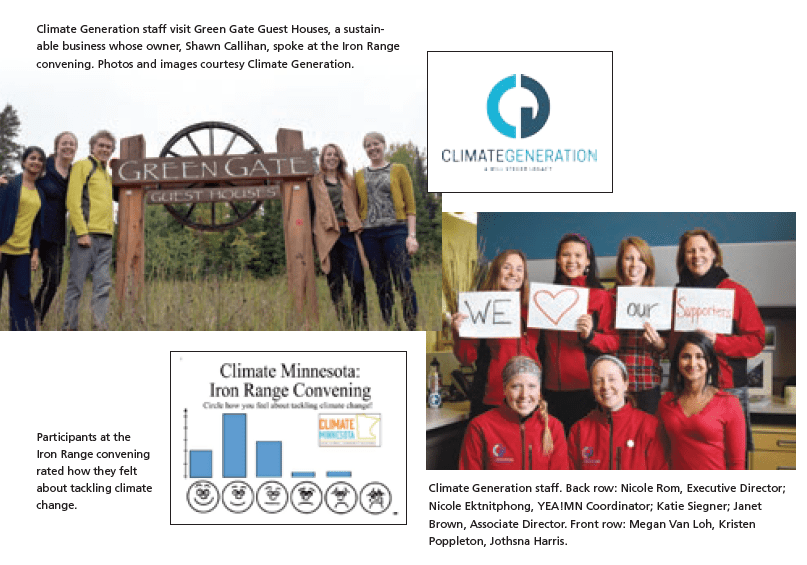

“I couldn’t believe what I read, but I knew it was a fact, and this made me realize that ‘climate change’ was happing right now. So I changed my life. I moved back to the city from my wonderful life in Ely, MN. in the wilderness and in ’05 started the Will Steger Foundation, now Climate Generation,” Steger told a group in Virginia, MN. last fall. The event that brought them together was part of a major public engagement initiative, Climate Minnesota: Local Stories, Community Solutions. Over the last 10 years Climate Generation has successfully led innovative climate change solutions in the areas of K-12 education, youth leadership and policy development. The Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources and the McKnight Foundation provided funding for Climate Minnesota to host 12 climate change events across the state.

From the West Metro to Duluth to the Iron Range, people got up close and personal with climate change. They learned how it would affect their communities, what people were doing to find solutions, and how they could take action themselves. And while science and facts were part of the lineup, another ingredient played a key role: storytelling. Community members from each location shared their personal experiences with climate change, transforming the topic from something large and impersonal to something concrete and local.

Personalizing climate change

According to Jothsna Harris, Education Coordinator for Climate Generation, the approach to the convenings grew in part from the reception that Steger’s eyewitness testimony had received. By providing a visual example of how climate change is playing out— especially one that came from his own experience—he drew thousands of people into the conversation. Climate Generation built on that by recognizing that everyone has stories to tell, especially since the impacts of climate change are no longer isolated to the polar regions and are being felt across Minnesota.

“It’s not just the eyewitness account of a few people. All of us can share what we’ve experienced. Maybe we don’t think we have a climate change story, but when you brain storm and do some digging, we all have the ability to think about how we’ve experienced climate change and have thoughts about the future,” Harris said. Sharing those stories has become a powerful tool for Climate Generation. “Stories speak to us in different ways than science and policy because they place abstract facts and figures into context.”

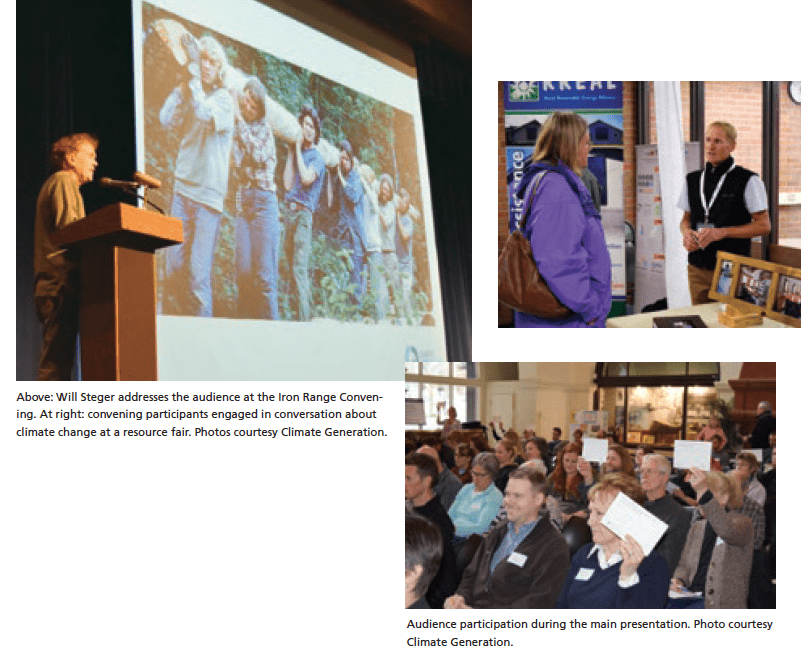

When Steger shared his stories at the Iron Range Convening in Virginia, he spoke to about 80 people—a small crowd compared to locations like Duluth where 150 people showed up. It was an older group, too, mostly retired. According to Harris, the energy felt different than other convenings. There was a more palpable tension, and one man made it known that he was there to disrupt the program. Knowing his intent, convening organizers made some changes to the schedule so it could flow without interruption. Virginia was also one of two communities where potential speakers declined to participate because they didn’t want to be associated with climate change. At the same time, however, Harris noticed a passion and a hunger for the conversation. There were a lot of people trying to create change in their community and others who weren’t sure what to think, but were curious to learn more.

The atmosphere wasn’t necessarily a surprise. Climate Generation’s Director of Education, Kristen Poppleton, pointed out that localization and knowing the community are critical to talking about climate change. “One of the things when we talk about the issue of climate change is how do you frame this issue to meet the community where it’s at? How can you listen? You have to listen to the community to understand why they would even care about this,” she said.

In urban communities, for example, the way to address climate change may be addressing high asthma rates due to the presence of an incinerator. On the range, where many people are living at the poverty level and view the loss of mining as a loss of livelihood, the focus may need to be the impact of climate change on tourism—something often touted as way to build up the economy. That’s why each convening was tailored to the community, partnering with local leaders and organizations to make it feel like a local event. In Virginia, community leaders helped welcome participants. Three other community members told stories about their observations of climate change and their work toward solutions. And local organizations like the Iron Range Partnership for Sustainability and the Rural Renewable Energy Alliance participated in a resource fair before the convening or led workshops at its close.

“It’s about connecting head to heart so it’s not just an intellectual issue but a local issue that’s impacting all of us in some way,” Poppleton explained.

Giving people a way to engage

In addition to framing climate change as a local issue, Climate Generation sought to engage people in the conversation right from the get-go. “After the welcome we asked a series of connecting questions throughout the program to speak to the emotional rollercoaster people go through when they learn about climate change,” Harris said. The first question prompted people to share what they valued most about their community, and in Virginia, nature rose to the top of the list. “People thought they were coming to a forum to listen and it became this moment where they were going to blurt out this one word and now it’s become a two-way conversation.”

Later, the audience weighed in on how it felt about the impacts climate change would have on the things they valued most, and how they felt about tackling climate change. John Latimer, a phenologist who told his story at the Iron Range convening, suggested that people crave conversations about the natural world. He hosts a two-hour radio show on nature— what he’s observing, what listeners are observing and how it compares to the average—on KAXE, Northern Community Radio in Grand Rapids. He started the show over 30 years ago, and he has noted changes related to climate change. Quaking aspen break leaf bud earlier. During winter, the minimum lows aren’t as cold as they once were. Animal and bird populations are shifting. Yet the other thing he’s observed is that people want to talk about nature. Reflecting on the show’s beginning, he said, “This was before social media and before email, and a lot of the community was talking to me on the street, in the grocery store, or they would send me letters or write me postcards and tell me what they were seeing. It became obvious people were interested and tuned into nature and wanted to know more and share more.”

In a sense, the storytelling approach at the convenings offers an evolution of the conversation. “It gave a chance for people to say in their own words what it means to them, what it’s like to live in these times and to experience these changes. It was a very powerful way for people to express themselves about what is happening in their world,” Latimer said.

The results that Poppleton and Harris see confirm the convenings’ impact. Participant surveys showed that respondents became more comfortable talking about climate change and 89 percent reported taking some kind of action afterward. “Roughly ninety percent of people doing something is phenomenal,” Poppleton said. “The grand majority of attendees were hopeful and energized and ready to do something.”

In upcoming issues of Wilderness News, we’ll take a look at the specific impacts of climate change on northern Minnesota. We’ll also meet individuals affected by climate change and working toward solutions. You can find more about Climate Generation and storytelling at: www.climategen.org.

In the meantime, tell us—what do you value about northern Minnesota and the Boundary Waters? Please post a comment below.