A 200-acre site where Indigenous people extracted copper ore for thousands of years has been given an important historic designation. The National Park Service recently approved an application to name the Minong Mining District — on what’s now known as Isle Royale — a National Historic Landmark.

Minong is the Ojibwe word for Isle Royale. People began extracting copper on Isle Royale at least six millennia ago, starting around 4500 BCE. In the 19th century, European immigrants noticed the evidence of that mining activity, and commenced another significant mining era at the site around 1870.

“In the opening of our principal mines we have followed in the path of our ancient predecessors, but with much better means of penetrating the earth to great depths,” the Minong Mining Company boasted in 1875.

During the second half of the 1800s, the region including Isle Royale and Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula produced more than half of the world’s copper. The largest and most productive 19th-century mine on Isle Royale, the Minong Mining Company, extracted more than half a million pounds of copper in the nine years between 1874 and 1883.

The merging of the two stories, the archaic mining before European contact, and later, industrial extraction, are still well represented at the site.

“Both precontact and historic mining remains in the Minong Copper Mining District are mingled in a way that serves as an outstanding example of the broader human history of copper mining in the Lake Superior Basin,” the application reads.

Prehistoric copper mining in the Lake Superior region is among the oldest known examples from around the world of humans utilizing metals. Copper from Isle Royale and the surrounding area was used in jewelry and ornamentation, and as tools such as arrow and spear points.

Lake Superior copper has also been found at prehistoric sites around the eastern United States, illustrating its value for trading, and the extensive networks that could transport goods halfway across the continent.

Not only does the Isle Royale site have a long history of copper extraction, but also played a significant role in archaeology itself.

“The Minong Copper Mining District figured prominently in several early archaeological investigations, contributing to the development of archaeological science with respect to understandings of Indigenous copper mining,” the National Park Service says. “Much of our modern archeological knowledge of Indigenous native copper mining methods stems from field research undertaken at this site.”

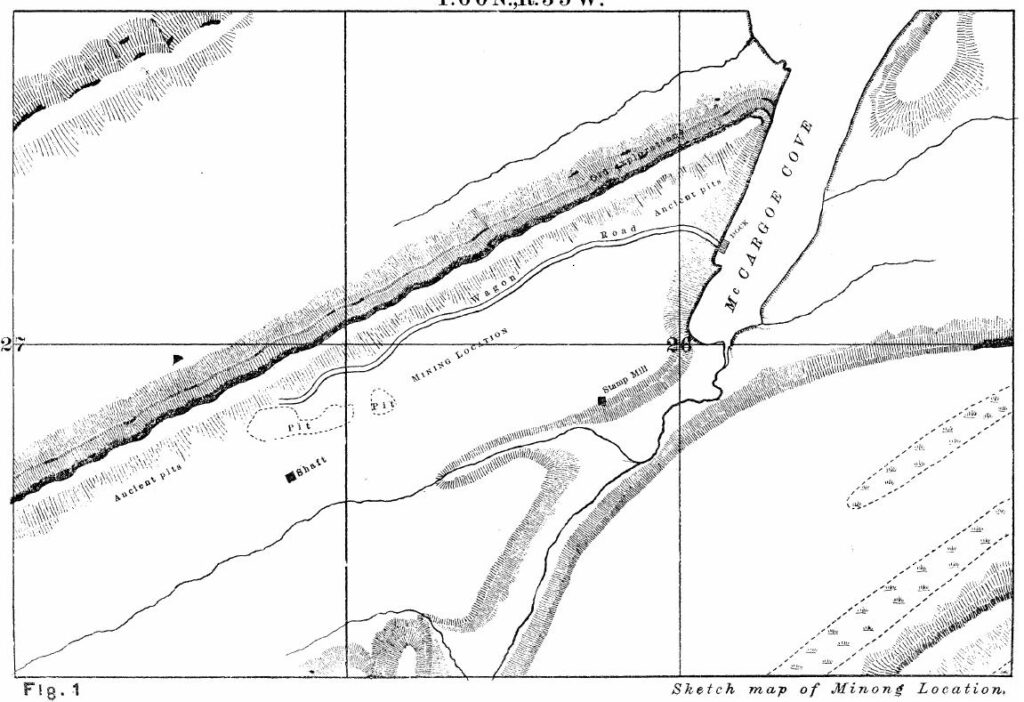

The Minong Mining District is known for more than 1,000 pits dug by Indigenous people, and evidence of how they extracted and processed the metal. The site was a rare and important resource because it featured “native” copper very close to the surface. Such copper exists in a raw, concentrated form and can be worked directly into usable material without any heating or other processing.

Miners at the site would use stones to smash apart bedrock they had excavated, revealing the copper embedded within. Later European mines included open pits and underground shafts, and left much of the surface evidence undisturbed.

“This National Historic Landmark designation for the Minong Copper Mining District cements its stature as an exemplary archeological site,” said Isle Royale Superintendent Denice Swanke. “Indigenous mining activities figured prominently in the park’s 1931 enabling legislation and the district benefits from being in designated wilderness within a national park, which will help ensure retention of a high level of integrity.”

In the mine’s most productive era of the 1870s, several large masses of copper were discovered. A nearly 6,000-pound nugget found in 1874 showed signs of prehistoric workers.

“The surface of the mass had evidently been beaten up into projecting ridges… depressions, several inches deep, and the intervening elevations, with their fractured summits, covering every foot of the exposed superficies,” according to an archaeologist. Later in the decade, a copper mass weighing six tons was found, as well as two nuggets weighing 3,317 and 4,175 pounds respectively. The nomination report was authored by Dr. Daniel Trepal of Michigan Technological University.

National Historic Landmarks have been determined by the Secretary of the Interior to be nationally significant in American history and culture. Potential landmarks are first evaluated by the National Park Service, reviewed and recommended by the National Park System Advisory Board, and signed by the Secretary of the Interior.