The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released documents last week that it had long kept secret about staff concerns over the PolyMet mine project in northern Minnesota. The agency made its comments public in response to legal pressure from environmental advocacy groups and Congresswoman Betty McCollum (D-MN).

The comments show the federal agency’s staff had serious concerns that the water quality permit the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency was developing would not adequately regulate pollution. The release also prompted accusations of a cover-up, leading the EPA Inspector General’s Office to open an investigation.

First reported by the Timberjay, the EPA’s comments say the water quality permit failed to restrict discharge from the project site to downstream waters, and the maximum levels it did include were much looser than required by law.

Permit problems

“The draft permit does not include water quality-based effluent limitations (WQBEL)s for pH or any other conditions that are as stringent as necessary to ensure compliance with the applicable water quality requirements of Minnesota, or of all affected States,” EPA staff wrote. “Furthermore, the permit includes technology based effluent limitations (TBELs) that are up to a thousand times greater than applicable water quality standards.”

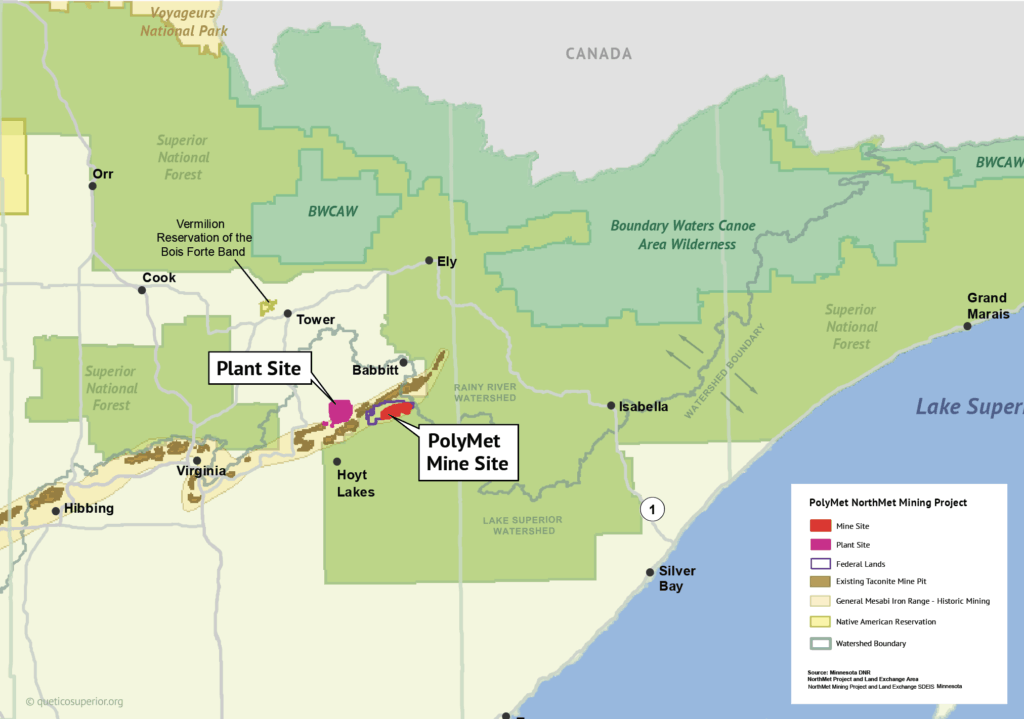

In particular, the mine was expected to release “significant amounts of mercury into downstream navigable waters.” Fish in many waterbodies in northern Minnesota are already contaminated with the toxic metal. The Minnesota Department of Health found that one in 10 babies born in the Lake Superior basin (where PolyMet’s mine would be located) have excessive amounts of mercury in their blood, which can impede brain development.

Other concerns included language that might make it impossible to enforce the Clean Water Act in regards to the project, and would let PolyMet and the MPCA revise the permit in the future without involving the public.

“These comments reveal that EPA was highly critical of the draft PolyMet permit,” said Paula Maccabbee, plaintiff WaterLegacy’s attorney. “In fact, EPA had concluded that the permit would violate the Clean Water Act since it had had no water quality-based limits on pollution. This major deficiency was never fixed by MPCA.”

The MPCA responded that it had received the comments over the phone, rather than in writing. But state agency staff who were on the call destroyed their notes afterwards.

“Similar to other complex projects, the MPCA and EPA had frequent conversations during the entire permitting process to discuss technical items,” said the agency’s director of communications, Darin Broton. “Based on those conversations, as well as other comments received from the public during the official comment period, the MPCA made substantive changes to the draft permit, including additional operating limits for arsenic, cobalt, lead, nickel, and mercury; and new language was added that clearly states that the discharge must not violate water quality standards. That’s why the EPA did not object to the MPCA’s final permit.”

Suppressing the story

Retired EPA attorney Jeffry Fowley also filed a sworn affidavit last week that accuses an MPCA leader, possibly former Commissioner John Linc Stine, of conspiring with regional EPA director Cathy Stepp to suppress the comments. On Wednesday, June 12, the EPA’s Office of Inspector General notified Region 5’s Stepp that it was opening an inquiry.

“The OIG’s objective is to determine whether the EPA followed appropriate Clean Water Act and [National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System] regulations to review the PolyMet permit approved by Minnesota and issued in 2018,” wrote Khadija Walker, Acting Director, Water Directorate, Office of Audit and Evaluation.

The agency requested “analysis and meeting documents from all staff and management related to the review.”

National advocacy group Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, PEER, which was part of the lawsuit that secured release of the comments, said the EPA’s behavior is part of a national trend.

“Under the current administration, EPA is a pollution watchdog not only on a leash but under a muzzle, as well,” said PEER Science Policy Director Kyla Bennett, a scientist and former EPA attorney. “As this PolyMet case demonstrates, Administrator Andrew Wheeler’s policy of ‘deference to the states’ functions as an abdication of EPA’s core mission.”

PolyMet received its water quality permit from the MPCA last December, marking one of the final steps before the company can start construction. WaterLegacy and other environmental groups have filed lawsuits challenging several parts of it. The suppressed EPA comments are a key part of their legal strategy to widen the possible evidence for courts to consider.