In late March, I reported on the boreal birds who make a home in the bogs of northern Minnesota during the winter time. One of the prime locations internationally known for seeing these birds is in the Sax-Zim Bog, near Meadowlands, Minnesota, which was experiencing an influx of tourists and birders at the time. I wondered if there were similar, less travelled, bog-like habitats in or near the Quetico Superior Wilderness Area. As this is the southern tip of the boreal forests from Canada, similar habitat seemed likely. Additionally, while researching that habitat near the Sax-Zim Bog, I learned that nearby tracts of land with bogs and fens have been purchased or exchanged in order to form what is known as wetland mitigation banks.

These are different kinds of forests and habitat than what is traditionally associated with the North Woods. As they occupy ten percent of northern Minnesota’s landscape, the boreal environment enticed us to learn more. What really is a bog? What is a fen? What is a peatland? How are these habitats considered to be wetlands? Following the advice of experts, we investigated the area near Cook, Minnesota, discovering a whole new world of wetland habitat there. It was a frosty, blue-skied morning where we walked along a path of towering black spruce, and dense tamarack trees. What follows is an educational introduction to these related topics.

To understand bogs, one must learn about wetlands, a collective term encompassing different kinds of water-saturated environments. There are several terms for habitats that are used interchangeably to describe wetlands. These include peatlands, bogs and fens. In Northern Minnesota, they are a predominant and valuable natural resource.

A wetland consistently has a water table close to or at the surface. In the northern coniferous forest region of Minnesota, a significant portion of the wetlands are covered with highly organic material that is slowly decomposing. These are known as peatlands. Every bog is both a peatland and a wetland, but not every wetland is a peatland or bog.

“A peatland is a type of wetland that has high organic soils to a certain depth. This organic matter is filling up from the ecosystem that has grown and died there and laid down in the wet soil yet has not decomposed because there’s really low oxygen conditions in the saturated soil,” explains Emily Toner, a soil geologist and Fulbright National Geographic Fellow.

What is a Bog?

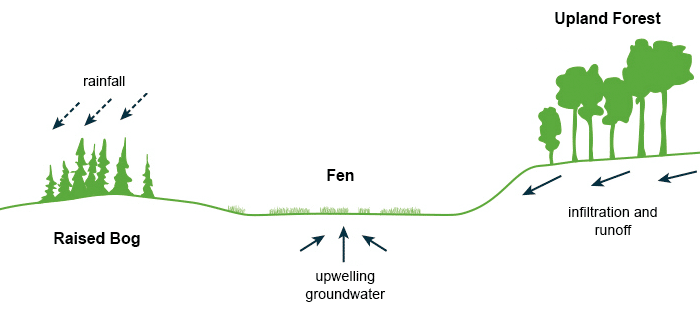

A bog is a freshwater wetland of spongy ground consisting mainly of this partially decayed plant matter, peat, which builds up and becomes elevated over time. It is highly acidic because it gets its water only from precipitation and is cut off from the flow of ground water and run-off. It often develops in old lake basins or kettle lakes with poor drainage which were originally created by glaciers, reports National Geographic. As detritus from large plants nearby die and sediments accumulate onto the glacial till deposits at the bottom of the basin, the lake becomes more shallow. Algae, floating-leaved aquatic plants and sedges expand across it. In successive stages, submerged plants grow underwater followed by emergent plants above the surface. Over time, as the wetland basin fills, a floating mat of the vegetation and sedges increases in density, decomposing slowly. This is peat. On top, a layer of sphagnum moss grows, conducive to this cool, anaerobic environment. Eventually, but not always, a coniferous forest develops, growing on top of the peatland bogs in Minnesota.

What is a Fen?

Fens are another important type of peat-forming wetlands. They are found throughout northern Minnesota’s boreal landscape. Unlike bogs, they rely on groundwater input and have access to surface water. They require thousands of years to develop. Once destroyed, it is difficult to restore them. Their soils are mineral rich. Often, northern Minnesota’s fens are very wet, without many trees. Instead, they are dominated by sedges.

The area where we went birding for boreal birds in Cook, Minnesota is considered by AmberBeth VanNingen of the Minnesota DNR to be a forested rich peatland with its dense, tall black spruce and heavy tamarack trees lining Johnson Road. This is a part of a mosaic of habitats related to a fen-system, influenced by groundwater, in the Cook, Minnesota area, as well as the area near the Sax-Zim Bog. The evergreen trees here, like a predominant presence of Black Spruce and Tamaracks, are more robust due to the nutrient rich soil.

American grass-of-Parnassus at Winter Road Lake Peatland SNA. Photo MN DNR, Fred Harris Bog copper butterfly. MN DNR, AmberBeth VanNingen Funnel weaver spider web with pitcher plant behind it. MN DNR, AmberBeth VanNingen

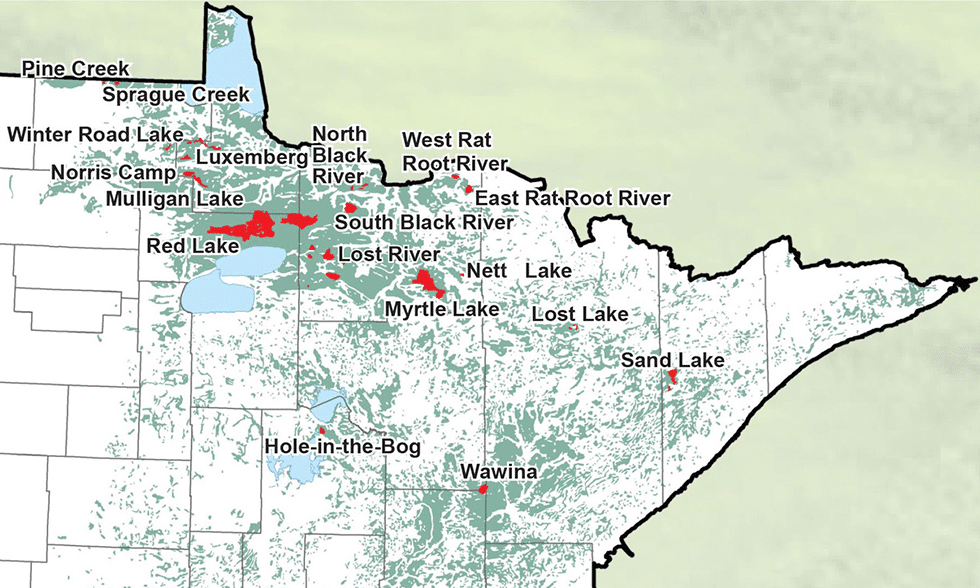

The 6-plus million acres of peatlands in Northern Minnesota are considered by some to be the last of its true, untouched wilderness and its most valuable ecosystem. They are the greatest amount of natural wetlands in the lower 48 states. More than 80 percent of the wetlands here are still intact and undisturbed from pre-European settlement years. Near the Lake Vermilion Soudan Underground State Park, naturalists lead scenic hikes out into the Lost Lake Peatland SNA to learn about its ecosystem and unique bog plants.

In his book, Minnesota’s Natural Heritage: An Ecological Perspective, John Tester describes three reasons why ecologists have focused intently on the wetlands from the cool, northern climate of Northern Minnesota: 1) their distinctive characteristics; 2) their high sensitivity to disturbance and 3) their potential value as an energy source. In addition, wetlands pose a possible risk for the release of carbon dioxide as the climate changes and warms up, or, as a result of drainage and disturbance.

Distinctive Wetland Characteristics

“Wetlands are highly productive and biologically diverse systems that enhance water quality, control erosion, maintain stream flows, improve the water supply, sequester carbon, and provide a home to at least one third of all threatened and endangered species,” reports the National Park Service. In Minnesota, this includes providing breeding habitat for the boreal chickadee and Minnesota’s rare and sparsely distributed Connecticut Warbler who nests in the sphagnum moss. Dr. Alexis Grinde, of the University of Minnesota Duluth, Natural Resource Research Institute (NRRI), will be studying these two birds this summer in the Red Lake Peatlands area. “Potentially, if we learn more about the peatland ecosystems we can develop strategies for the long-term conservation of high quality habitats and mitigate the impacts of climate change on the birds,” she explained.

Throughout the world, peatlands offer similar benefits to wetlands, one of which includes the ability to sequester carbon two to four times more than that of a terrestrial forest. Through photosynthesis, carbon has entered the plant tissues that make up the organic vegetation in the peat. This carbon is locked away in the peat soils, providing a valuable carbon store.

The peatlands of north central Minnesota are unique. Here, a vast landscape of relatively undisturbed bogs and fens exist in this colder, boreal region where researchers find it easy to access. This access enables further studies on peatland development, the hydrology of large expansive peatlands, flow patterns, ecological processes, carbon sequestration, biodiversity, forest management and impacts on peat from climate change. Expansive peatlands existing in Canada and Siberia are not as easy to study due to the disturbance from commercial use.

In Northern Minnesota, peatlands receive much more precipitation with less evapotranspiration, meaning water does not move from the ground through the trees and plants to the air. With high acidic levels, and saturated soils, it’s conducive for the growth of peat. This is particularly true in the famous Red Lake Peatlands, north of Beltrami, Minnesota, a scant fifty miles east of the Prairie Forest border. The significance of this location is its contrast in bordering Prairie Forest habitat, where evapotranspiration happens in greater levels, reducing the water levels on the ground, thus, the ability for peat to grow. This difference of peat growth in a proximate location offers a point of distinction to further research. For further information, see the DNR web site for the Minnesota Scientific and Natural Areas Patterned Peatlands or an informative book, The Patterned Peatlands of Minnesota, edited by H.E. Wright, Jr., Barbara Coffin, and Norman E. Aaseng.

Barbara Coffin, says of their research: “Little did we know back in the 1980s that peatlands would figure so importantly in the problem of global climate change. Peatlands store vast quantities of carbon – pulled by plants from the atmosphere over millennia, and now with a warming climate increasingly subject to decomposition and release as greenhouse gasses, CO2 and methane – representing a potentially large positive feedback on warming. A major whole-ecosystem experiment to look at climate effects on peatland ecology is now underway at the US Forest Service’s Marcell Experimental Forest near Grand Rapids, MN. The study, SPRUCE (Spruce and Peatland Responses Under Changing Environments) involves more than 100 university and agency scientists from all over the world and is coordinated and (partially) funded through the US Department of Energy’s, Oak Ridge National Laboratory.”

Located in the furthest southern tip of the boreal forests, the temperatures are slightly warmer here first. This has two implications for current research efforts. First, Minnesota’s boreal peatlands lack Permafrost – a deep freeze in the ground found in peatlands further north in Canada and Siberia. Groundwater hydrology can be studied more easily as a result. Second, as the climate warms up, this tip of the boreal peatlands will continue to be impacted first. These peatlands will be significant indicators on what happens with the release of such a vast amount of carbon, once the warmer temperatures dry the saturated soils, and oxygenate the peat. Conversely, scientists also are looking here to see how peatlands release methane gas, a greenhouse gas, as part of its natural process.

Vegetation in boreal peatlands are primarily in bogs and fens. The bogs, due to high acidity, do not provide high levels of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous for plant life. Usually, they are covered with sphagnum moss, sedges and shrubs that can grow in low alkaline conditions, like leather leaf and other plants from the heather family. Some bogs develop forests with stunted black spruce and sparse tamaracks.

High Sensitivity to Disturbance

Due to the ecological importance of this natural resource, strict state and federal laws and processes have been established to protect wetlands. Planners of development projects that will destroy or impair a wetland, must purchase wetland mitigation credits within a restored wetland, properly, in the same watershed in order to offset the damage. The restored wetland area offering these credits is what is called a Wetland Mitigation Bank. Once a piece of land is officially determined to be a part of a wetland mitigation bank, it’s similar to an easement in perpetuity where no further development can be planned or built on the land.

Near the Sax-Zim Bog area, there are two examples of Wetland Mitigation Banks.

The first, the Fens Wetland Bank, is a 525-acre farm just north of Sax, formerly owned by Chun King food mogul, Jeno Paulucci. Despite the name, Sax-Zim Bog, most of this area, including where the former farm sits, is actually a fen-system. “There may be some pockets of bog in that whole area, or some small raised bogs there above the groundwater table, but it’s mostly a large fen system,” explains Kurt Johnson. Johnson is the Research Program Manager for Applied Peatland/Wetland Research at the University of Minnesota Duluth, Natural Resources Research Institute (NRRI). He also has provided research related to the Fens Wetland Bank.

When Paulucci tried to drain his property in order to raise vegetables for Wilderness Valley Farms in the 1960s, it wasn’t highly successful due to the high levels of moist soil in this swampy area. More fitting for this land is what the University of Minnesota, Duluth, NRRI currently has in place – efforts to convert and restore it back to its natural habitat, wooded swamp and a peat bog. In this process, Johnson applies his research into what it would take to restore the disturbed peatland that was growing here. His studies also help determine how to safely harvest some of the peat for soil. Commercial partners use the peat as a horticultural soil supplement.

In addition, the Fen Wetlands Bank is the United States’ first wetland bank to provide a mix of wooded swamp and peat bog as mitigation credits. One of its biggest customers is the Minnesota Department of Transportation, who purchased the credits in the mid-2000s in order to pursue developing and expanding Highway 53 into four lanes between Virginia and Cook, Minnesota. This route is surrounded by wetlands.

The second and more recently developed Lake Superior Wetland Bank, also surrounds the Sax-Zim Bog area. Its 2,400 acres of bogs and wetlands stand as the largest for-profit wetland mitigation bank in the country. It was created in 2015 by a private investment company from Baltimore, Ecosystem Investment Partners (EIP), who purchased a sizable tract of harvestable forest land from Potlatch in northern Minnesota. In St. Louis County, a myriad of land tracts were pieced together consisting of various wetlands and bogs primarily located on tax-delinquent properties owned by the county and the state. Through the non-profit, Conservation Fund, which acted as a broker between the county and EIP, a complicated land exchange was facilitated, in effect, trading the newly acquired forest lands from Potlatch in the north for these public tracts of wetland habitat in St. Louis County.

The main focus with these former farmed lands is to remove the drainage ditches and restore the wetlands.

As a result, EIP now owns these wetlands, which were set up as a wetland mitigation bank. Accordingly, they now pay taxes on these properties, for the first time in years. Proponents of this mitigation bank advocate that this allows private developers and regulators, like mining companies, or state agencies building roads, to offset the wetland disturbance of their project through restoring wetlands in this particular bank. In addition, birdwatching groups, like the Friends of the Sax-Zim Bog, endorse having vast surrounding acreage of wetland habitat secured from future development for the benefit of the birds.

Concerns here include the timeline for restoring peatlands potentially not being long enough to make this determination of restoration. Since peatlands take centuries to restore, the desired results are not guaranteed. Sphagnum moss and other related species in the peat family, however, can be restored more quickly. Conversely, others contest the lack of substantial data or Environmental Impact Plans that these existing wetlands are truly in need of restoration. The determination of comparable ecological value for each mitigation credit is complex.

Peat – Stored Carbon, Energy and Climate Change

Scientists are looking at how peatlands will potentially impact global warming. With all of its stored carbon, peatlands have the potential of releasing a great deal of carbon dioxide. When the temperatures rise, and water levels drop, the peat is dried and is exposed to oxygen. This starts the decomposition process, converting carbon to CO2, triggering its release. So, learning how to manage water levels to keep the carbon stored is important. Water levels and chemistry also impact the vegetation that will grow there. In the cases where peat has been mined, particularly in peatlands that are fens with mineral soil, restoring the hydrology is key.

For centuries, people have been using bricks of peat as fossil fuel to cook and heat their homes. In Ireland, where 20% of their landscape on the western coastline is peatlands, this is still a common practice, describes Emily Toner. “Peat was a precursor to coal,” she reminds us.

Here in Minnesota, the peat has been mined for commercial soil additives. Each time peatlands are disturbed, for energy, for mining, for harvesting of commercial products, great care and caution is needed. In the past, several attempts have been made to harvest peat as energy, by both the state of Minnesota and private companies. Disturbing peatlands for energy or horticultural reasons is also a concern in England where using peat has become taboo. In Canada, new research is underway on how to use peat as a biomass, or a biochar for energy purposes. This would be used as an alternative to coal to produce bioenergy from existing coal-fired power plants in Ontario that have already been shut down, reports Science Direct.

Clearly, the peatlands, bogs and fens in Northern Minnesota not only offer a day of wonderful birdwatching in the bogs, they offer great value for many and are a proud asset of Minnesota’s natural heritage.

More Information:

Minnesota Scientific and Natural Areas Patterned Peatlands

Lost Lake Sanctuary, Minnesota Conservation Volunteer

Anne Queenan is a writer/photographer/video producer who reports on natural heritage, watershed health and land stewardship. She and her dog Coda live on the Mississippi River in Minnesota where she enjoys paddling, birding and scenic hiking.