Twenty-five years ago on Independence Day, thunderstorms wreaked havoc across northern Minnesota and beyond — with some of the worst effects felt in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

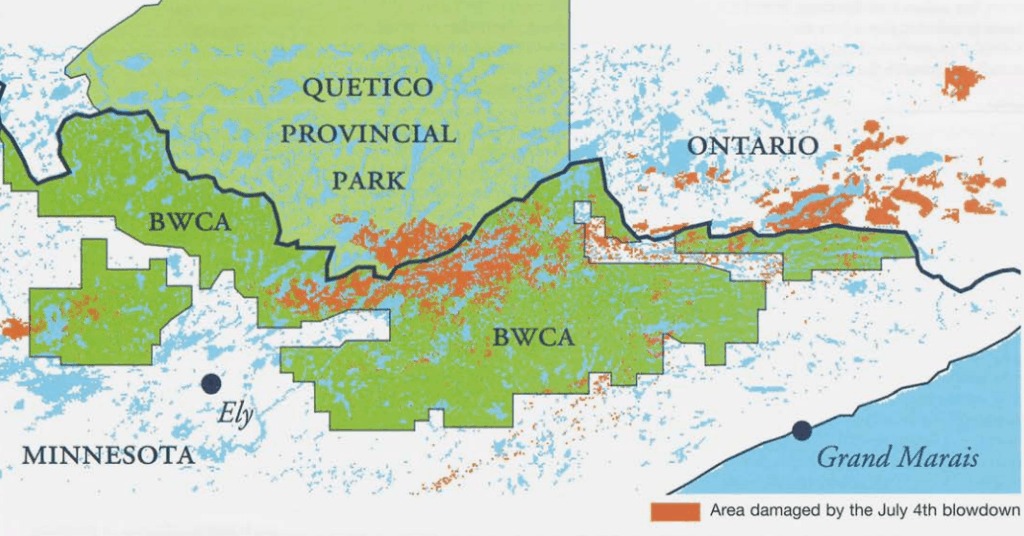

Approximately 20 million trees were knocked down by the powerful winds within the BWCA. The storm cut a swath through the wilderness 30 miles long and about 10 miles wide, or about 500,000 acres — nearly half its total area. In total, the derecho, an uncommon type of storm that produces powerful straight-line winds over long distances, did damage along a path more than 1,300 miles from the eastern Great Plains all the way to New England.

Wind speeds are believed to have peaked at 90 miles per hour, causing damage worse than a F-1 tornado, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“The first large swath of intense forest destruction occurred while the storm was still west and northwest of Ely, MN about noon. This first swath was approximately five miles wide and 25 miles long. There was a second damage swath in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW). This began after the northern part of the storm passed east of Ely and accelerated into a well-defined bow-shaped echo, about 1230 p.m. Moving through a wilderness area, no wind speeds were measured. However, 478,000 acres of forest, in a swath 12 miles by 30 miles, was leveled and completely destroyed. Access to the area was blocked by tree trunks, many stripped of their bark, blown into drifts 15 to 20 feet high.” – National Weather Service, Boundary Waters Windstorm The Blowdown of July 4th, 1999

The storm’s path through the wilderness went northeast from Ely to the Gunflint. While the storm resulted in the death of two people in Canada, there were no deaths in the Boundary Waters, despite occurring on the busy holiday weekend. It took nearly two weeks for all people who had been in the wilderness to safely get out, with 60 people injured, and portages obliterated by fallen trees.

Personal accounts of the aftermath

Forest Ranger Bruce Slover in Ely observed: “This was a massive event. What strikes you is all the timber laying in one direction. Whole areas are just stripped. There are just saplings standing. This must be what it looked like in 1910 or 1920 at the end of the logging days.”- Wilderness News, Fall 1999

“I have traveled the world for (National) Geographic and photographed and documented some great natural events and catastrophes, and always found that I could deal with it and shoot it and come back with information. In this case having flown over the Boundary Waters yesterday, it was difficult for me to shoot. Emotionally it was a bit startling. Looking through the viewfinder of a camera limits your sense of place. I wanted to see it without any obstruction. So I was just simply awestruck at the sheer size and breadth of the destruction.” – Jim Brandenburg to MPR, Wilderness News, Fall 1999

An ecological ‘gold mine’

Despite the danger and destruction, the blowdown became a valuable laboratory for scientists.

“Ecologically it’s a gold mine,” said Chris Peterson, a forest ecologist at the University of Georgia who specializes in wind disturbance.

The forest itself jump-started a new phase of succession, with balsam fir, black spruce, and northern white cedar sprouting quickly in the suddenly sunny woods. Powerful downbursts were hardest on large trees of all species, particularly hitting red and white pine. The wind destroyed 13 percent of the old growth stands in the wilderness, a rare resource in the area, much of which was once logged before wilderness designation.

This change in forest in led to a change in insects and other food sources for birds, changing what species were observed. At long-term study sites, the bay-breasted warbler disappeared, while blackburnian warblersalso declined. On the other hand, magnolia warblers, white-throated sparrows, chickadees, and woodpeckers were “much more abundant.”

The rarely-seen yellow-bellied flycatcher started appearing at blowdown monitoring sites the first year after the storm and was common for at least the next few years. Researchers say the upturned tree roots provided an abundance of perfect nest sites for the bird.

Long legacy

The storm also highlighted holes in emergency warning systems. While the National Weather Service was aware of the storm as it developed and moved east, there was no way to contact people camping in the wilderness. As a result of the storm, three NOAA Weather Radio transmitters were installed in Ely, near Gunflint Lake, and near Grand Marais.

In the Boundary Waters, the legacy of the 1999 storm has been long-lived. The Superior National Forest undertook a prescribed fire program intended to reduce fuel in the wilderness that could cause fires that threaten areas outside, with burns still occurring as recently as 2016. Major wildfires, including the Cavity Lake and Ham Lake fires in 2006 and 2007, respectively, both burned partly in blowdown areas. The 2011 Pagami Creek Fire did not burn significantly in blowdown areas.

This video by the American Museum of Natural History, which was released in 2012, features interviews with people who experienced the storm, and scientists who study it:

Read our original coverage in Wilderness News Fall 1999

and Wilderness News Winter 2000.

More information:

- The Boundary Waters – Canadian Derecho – NOAA

- After the blowdown: a resource assessment of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, 1999-2003 – U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station

- Boundary Waters Windstorm: The Blowdown of July 4th, 1999 (PDF) – National Weather Service

- Christine Mlot, The Perfect Windstorm Study: What happens when millions of trees fall down in a forest wilderness?, BioScience, Volume 53, Issue 7, July 2003, Pages 624–629, https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0624:TPWS]2.0.CO;2

- The 1999 Blowdown Storm: Looking Back After 20 Years – WTIP