The battle to spare the living wilderness is now living history

and the men who fought that battle are among our quiet legends.

Ober’s little island awaited it’s new mission and Ober himself spoke of his dreams for it’s future. He saw it as a place for musicians, artists, writers and teachers to come for a refreshment of tired souls. He saw it as a continuation of its role

as a special place to his Ojibwa Indian friends, the home of friendly spirit families. He saw it as a living island much as he saw his beloved boundary waters country as a living wilderness. These are the dreams he told to friends…

…today, Ober’s dream is reality

thanks to the Foundation that bears his name.

– Ted Hall, from the 1980-81 Winter issue of Wilderness News

The Dream Goes On: The Later History of Mallard Island

by Edith Rylander

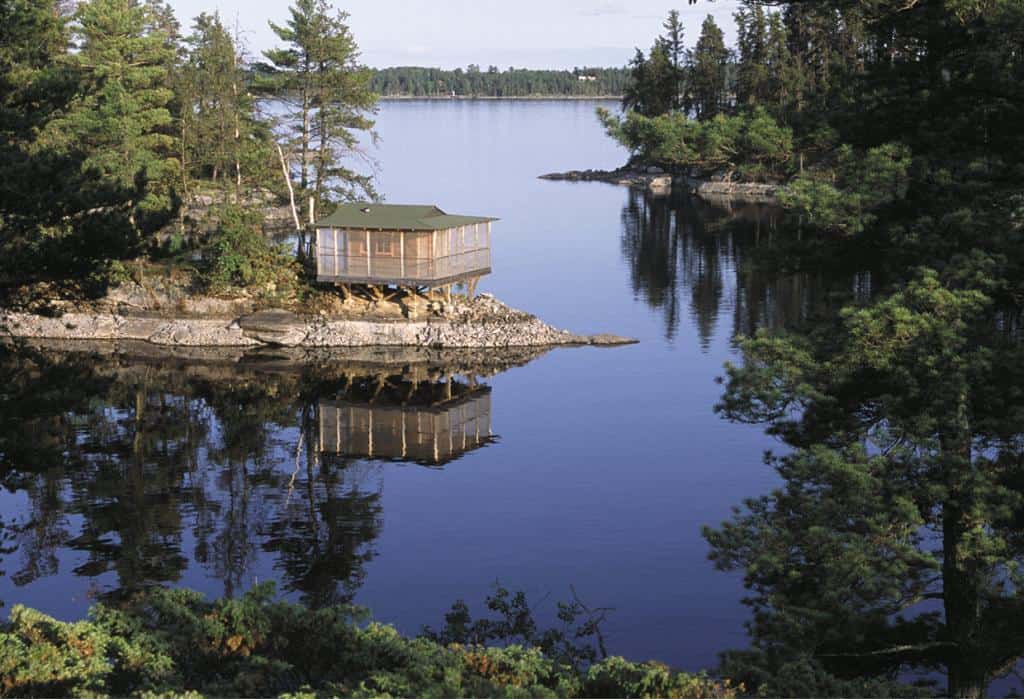

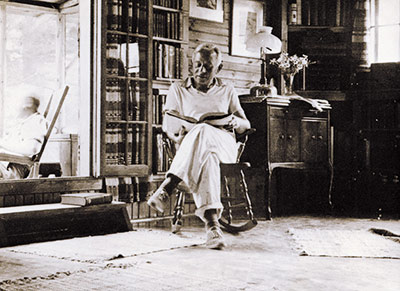

During Ernest Oberholtzer’s active years, the island he accepted in lieu of back wages in 1922 was, indeed, a university of the wilderness. Friends of the Quetico-Superior and founders of the Wilderness Society joined writers, painters, musicians, native berry-pickers and Rainy Lake neighbors at his table. They slept in Bird House, Japanese House, Front House, Cook’s House, Cedarbark House. They dipped into the ever-growing personal library of this most eclectic learner. They listened to him play the violin.

But when Ober died, in 1977, he had not lived on Mallard Island since the summer of 1957. The island had been visited, supervised, and briefly inhabited, Ober having given the keys to the Mallard to Bob Hilke in 1968, with instructions to watch over it. At the time of his death the buildings still contained Ober’s things, everything from his well-worn canoe to sheet music and letters from friends. But none of this treasure trove of history was in any kind of order. And what were his heirs, legal and spiritual, to do with it all?

There was a complex sorting-out process which was not without tension. At the core of it was the decision to maintain lands, buildings, and collections intact, as much as that was possible. The willingness of Ober’s heirs to share part of their inheritance assured that Ober’s legacy would live on.

Today, the Ernest C. Oberholtzer Foundation “maintains Ober’s island home as a place of inspiration, renewal and connection to the natural world.”

Well before legal niceties were completed, the massive task of sorting, repairing, reconstructing and classifying had begun. Much of the early work was done by Ted and Rody Hall and Gene Ritchie Monahan. Gene Monahan in particular organized numerous unbound, scattered papers to go to the Minnesota Historical Society. Jean and Randy Replinger

and a crew of volunteers sorted, organized, catalogued, and shelved the expansive library. Ray Anderson sorted and cataloged Ober’s amazing photographs. In 1985, the foundation selected its first program director, Jean Sanford Replinger.

These volunteers were merely the first of an enormous number of helpers who made buildings safe and habitable, restored crumbling masonry, cleared and re-planted Ober’s gardens, and replaced old-style outhouses with composting outhouses. Ober’s Island is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Even as the Mallard was restored and maintained, the program director has implemented summer programs designed to ensure wise use of

this unique island’s resources, including Ober’s personal legacy. These programs include “work weeks”, devoted to the well-being of the island’s buildings and collections, and theme-oriented programs. Painters, photographers, musicians, bird-banders, bibliophiles, writers, Ojibwe language learners and educators have met, mingled, learned, and shared, much as Ober might have wanted.

This article appeared in Wilderness News Summer 2004