In the summer of 2012, teenager Jessica Haines was riding home from a Boundary Waters trip with her dad, brother, and friends. They were stuck in traffic on Interstate 35 when she saw a billboard asking a simple question: “Sulfide Mining Near the Boundary Waters?” The question, posed by the Mining Truth coalition, piqued the Forest Lake high school student’s curiosity, leading her on a four-year search for an answer and an award-winning science project.

Three years into her study, Jessica says even if such mining near the Boundary Waters was done as safely in northern Minnesota as at the Wisconsin mine that is often held up as a poster child of modern mining, it could still have devastating impacts on northern Minnesota’s lakes, rivers, and groundwater.

When Jessica asked her dad what the billboard was about, he was able to reply with some firsthand knowledge. Gerard grew up in Ladysmith, Wisconsin, where the Flambeau copper mine operated in the 1990s. The mine is a frequent example of a relatively recent mine that prevented significant pollution. Governor Mark Dayton is planning to visit mines similar to the PolyMet proposal this fall as he prepares to make a decision about Minnesota’s possible first copper mine and there is a good chance Flambeau will be on the list.

“It was supposed to be the safest sulfide mine in the world, but it somehow still managed to occasionally pollute the Flambeau River,” Jessica remembers her dad telling her. Some people called it a success, other people called it a failure, so she decided to look into it for herself. By studying Flambeau, she set out to come up with a “best-case scenario” for PolyMet.

To see if its reputation as a clean mine held water, Jessica devised experiments and did in-depth research to understand the mine’s history, the chemicals still running off the site, and the impact on plants and animals. It wasn’t easy. Her first year’s experiment was “basically a failure,” she says, because her plans to take water samples from the creek that carries mine runoff toward the Flambeau River were stymied by drought.

She turned to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources for information that she couldn’t collect herself. After pestering the agency for data from its monitoring wells, they just gave her a massive report to dig through. It was there that she found the amount of chemicals that had been detected in runoff, allowing her to go to the next step of her study.

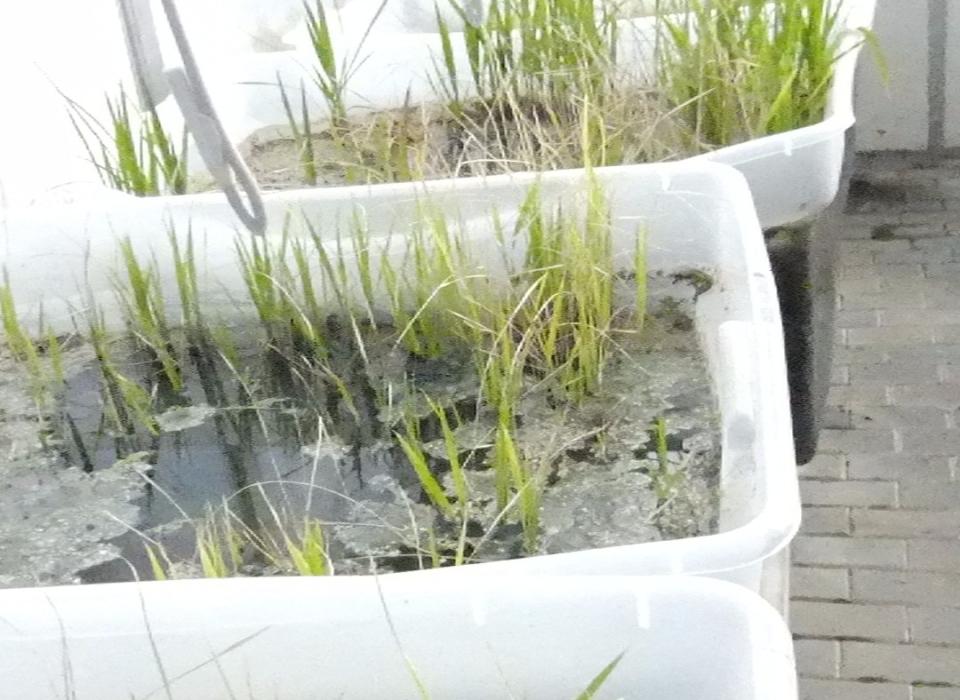

To test the harmfulness of the discharge, Jessica planted several small bins of grass and watered each one with chemical concoction from low to high concentrations of zinc chloride and copper sulfate, as well as a control subject that was lucky to get normal water.

The results were pretty obvious: The more of each chemical, the worse the grass grew. A year later, she replicated the process with a plant deeply important to the Boundary Waters region, to the Ojibwe culture, and to Minnesota’s identity: wild rice.

Interested by the research being done by the state of Minnesota to understand the impacts of mine waste on wild rice, Haines used copper sulfate at concentrations more like what could occur with a major spill from a mine, from 2,000 to 3,000 milligrams per liter (Minnesota’s controversial state standard is 10 mg/L). She also applied them at different stages of the plant’s life cycle. It didn’t matter what amount of contaminant or when it was applied, all the plants ultimately died. Her report reads:

“The higher concentrations of minerals either allowed no plant growth or quickly killed the plants they were added to. Lower concentrations also stunted growth and killed off some plants in the experiment. Also, the higher the mineral content in the water, the lower the pH results, making the water unable to sustain life.”

Following the completion of the wild rice study, Jessica’s project won at the Minnesota FFA’s science fair in March 2015. She has since submitted it for the agricultural education organization’s national competition. She is continuing the project this year as a high school senior, planning to complete one more phase of the research.

“Some mining companies will point to [Flambeau] as a mine that operated without damaging the environment, but that’s not true,” she says. “I have the DNR paperwork to prove it. There’s a sterile stream in which nothing has lived since after the mining commenced, and chemical-filled water is being dumped into the Flambeau River. Not to mention that the groundwater has been affected, and is effectively contaminated by the mining.”

That said, the student scientist thinks that someday, it will be possible to extract the minerals without harming rice and the rest of the ecosystem.

“We don’t have right technology to prevent pollution, and, even more importantly, to clean up any damage done,” Jessica says. “Maybe sometime in the future, probably still a few decades away, there will be a mine that can operate successfully without polluting.”

Whether or not PolyMet will have a shot at being that mine is something Minnesota’s governor and other authorities will soon decide.