On New Year’s Eve, moose researchers received an alert that one of the animals being tracked was possibly dead. The collar it wore detected it had not moved for several hours.

The monitoring program is designed to help scientists investigate the mysteries of why moose in northeastern Minnesota are dying. When they die, they are often quickly scavenged by wolves and other animals. It’s important for scientists to get there first so they can try to understand what killed the animal.

Researchers hurried to the location, and found the moose alive, but not healthy – it couldn’t stand or hold its head steady. When it died, it was found to have brainworm, a parasite that is believed responsible for the deaths of several Minnesota moose since the Department of Natural Resources started intensively investigating the dwindling herd in 2013.

After three years of study, in which 173 moose have been collared, researchers recently announced they are starting to get some ideas of why more moose are dying than naturally occurs. Last year, there were an estimated 3,450 moose in northeastern Minnesota, according to aerial surveys conducted by the DNR. Ten years ago, there were 8,160 – more than twice the current number.

The 2015 aerial survey found extremely low numbers of calves. The ratio of calves to cows was one of the lowest since 2005.

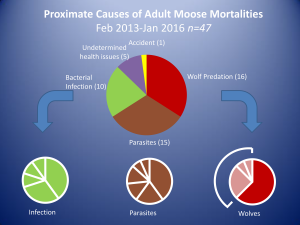

Suspected reasons for the population decline have included increasing wolf populations, climate change, tick infestations, and parasites. The scientists now say it appears wolves are not the primary culprit for the 47 collared moose that have died and been examined, but illness is instead.

“Two-thirds died from health-related causes,” the DNR recently reported. “Wolves killed one-third of those moose but sickness in 25 percent of those animals made them easy prey.”

Bacteria and parasites killed 31 of the 47 moose, while wolves killed 16. Researchers are starting to see evidence that warmer temperatures in winter are contributing to moose being more vulnerable to health problems.

“The heat stress index of moose is tracking very closely with the severity of winter nutrition of these moose,” Glenn DelGiudice, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources moose project leader told the Duluth News Tribune. “What it’s saying is that winter nutrition could be a key to this.”

Without the option to cool off in ponds and streams, like they can during the summer, moose can begin experiencing heat stress when the thermometer hits just 23 degrees. This can cause increased metabolism (and greater need for nutrition), faster heart rates, and increased breathing.

“If the effects of climate change are negatively affecting the nutrition of moose in winter, it could clearly make them compromised and more vulnerable to disease and other things,” DelGiudice said.

The researchers cautioned that the findings remain dependent on the anecdotal evidence of the collared animals that could be examined after death. They state that more study is needed to determine trends.