Expanded songbird surveys in northern Minnesota are giving scientists and land managers valuable new data. An inaugural report released last month by the Superior National Forest documents and analyzes data from five bird banding stations across the region during last year’s breeding season. Researchers say the information will help protect the species that breed in the southern boreal forest.

The report includes a new site launched in 2018 at the University of Minnesota’s Hubachek Wilderness Research Center near Ely. The site is the first one operated by the Superior National Forest. Biologists say adding the site will improve the statistical significance of the regional studies, and help monitor the status of fragile feathered creatures.

Knowing what the population is doing and why helps us understand the health of the habitat. Current concerns for the songbirds include habitat loss, climate change, and declines in their food sources, which are mostly insects.

“We care about conservation of birds, but we are also concerned about what our birds can tell us about the ecosystem as a whole,” says Forest Service biologist Sarah Malick-Wahls.

As the report says, birds populations can alert scientists and managers when something else is awry in the ecosystem.

Catch and release

At each site, expert bird banders set up large nets in forested areas. These fine and soft “mist nets” mostly capture the small songbirds that fly through the understory. They catch the birds without harming them, and the banding team checks the net almost continuously to remove birds and bring them to a banding station.

Then the bird species are identified, measured, their sex is determined, and a small metal band is placed around the leg, before it is released to the skies again. A number on the band allows banders and researchers anywhere in North America who may recapture the bird to learn about its history.

The five sites in the report are all part of the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) network, which includes more than 400 stations around the continent. In its 30 years of existence, data collected by the MAPS network have provided information key to bird conservation. Findings have included the importance of protecting wintering grounds and migration routes, which can in turn affect the success of next summer’s breeding, and the significance of weather and climate in bird reproduction.

Banding efforts in northern areas that are important for bird breeding can help explain why a certain species’ population may be going up or down. But habitat in the transition zones between hardwood and boreal forests are poorly represented in the MAPS network.

“Our goal in establishing this new fifth site in northeastern Minnesota was to gain the statistical power to detect regional trends,” says Malick-Wahls. “This gives land managers in the Arrowhead region, including the U.S. Forest Service, Superior National Forest valuable information in making management decisions that affect our birds in this specific place.”

The Hubachek Wilderness Research Center is on Fall Lake, on the edge of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. It includes 350 acres for a wide range of research, focused on how climate change affects northern forests, and for education.

The biologists say Hubachek is ideal for their bird banding efforts “because it has an existing network of trails with low use to facilitate efficient movement during net checks, has a comfortable cabin to serve as our processing station, a variety of habitats represented in close proximity, and friendly staff eager to assist.”

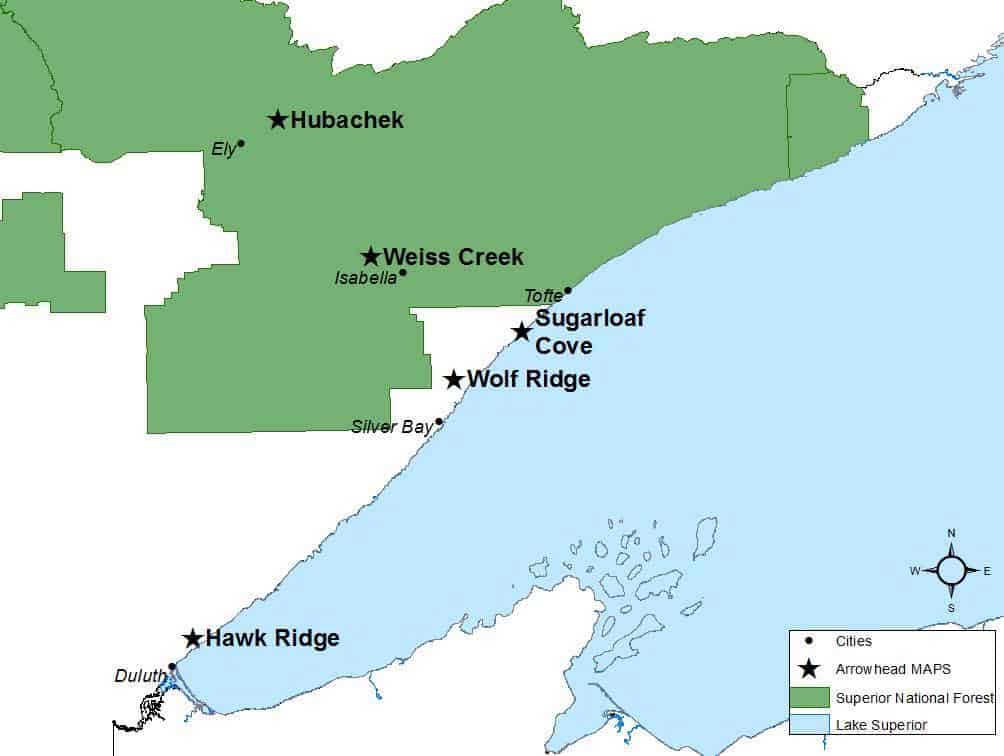

In addition to the new in 2018 Hubachek station, the Arrowhead’s MAPS sites include Hawk Ridge near Duluth, Wolf Ridge Environmental Learning Center in Finland, Sugarloaf Cove Nature Center in Schroeder, and the Weiss Creek site in Isabella.

Public involvement

Bird banding takes a lot of time and legwork. MAPS stations are required to follow strict protocols for their operations. They are to be open the nets seven times during a 12-week period, for exactly six hours each day. It’s all intended to help make the continent-wide data as useful as possible, standardizing the process so scientists can study the information and determine significant changes.

Volunteers are often very helpful during banding operations, and seeing the birds up close, even releasing them from one’s hand, can help instill a love of nature.

“This study provides countless opportunities to inspire young people in conservation of the natural world,” says Malick-Wahls. “We often host groups of kids and young adults at these banding stations for demonstrations. Nothing compares to the delight of holding a beautiful warbler in the palm of your hand and having the honor of setting it free.”

The first year of banding at the Hubachek Center resulted in 198 individual birds captured, representing 34 species. The five most common species in the nets were ovenbirds, Canada warblers, American redstarts, white-throated sparrows, and mourning warblers.

The results were encouraging to the researchers. In their report, they point out how the common birds at Hubachek are slightly different than at other stations, which demonstrates its value to the MAPS program.

Border Country birds

Six species in common were in the top ten most frequently captured from 2007-2018 at Wolf Ridge and Weiss Creek study sites: Nashville warbler, ovenbird, chestnut-sided warbler, American redstart, white-throated sparrow, and Canada warbler.

Even though all five banding sites are in the same forest biome, the data helps better understand specifically where certain species like to nest.

But it’s just a beginning. The true value of such an effort is the years of data collection and the information it can provide about birds and the ecosystem. After collecting five years of data from all the Arrowhead stations, the biologists can begin comparing annual trends, comparing them to broader regions, and aid conservation efforts in northern Minnesota.

“We are really looking forward to future analyses once we have more years of data from Hubachek,” Malick-Wahls said. “This study demonstrates the importance of long-term research, and of collaboration among researchers from different agencies, in order to understand demographic patterns and their drivers.”

The researchers still have questions about why certain species are showing low numbers because of low reproduction, or low survival of adult birds. More data will help. They point to the red-eyed vireo as one mystery, showing declining populations at some of the study sites. The scientists say the local loss of tree species the vireos seem to prefer, which had been blown down near some of the study sites during recent windstorms, may explain some of the trend, but probably not all of it.

Swainson’s thrushes are another species of concern, showing declining numbers both regionally and at the specific study sites. Again, local conditions may be affecting results, as the Weiss Creek banding site had seen an extensive spruce budworm outbreak in recent years, which had killed many of the understory trees the birds frequently nest in.

But declines in both species have been seen recently on a regional scale, which indicates it isn’t only local trends. By comparing the standardized data from MAPS with other forms of bird population monitoring that are ongoing in the region, even more can be understood about the data and the birds.

“Songbirds are an important component of our northern ecosystems for their role as insect and seed consumers, food for larger animals, and for the joy their musical vocalizations and colorful plumage bring to those that make the effort to take notice,” the report reads.

More Information:

- Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship, Long-term research at the Hubachek Wilderness Research Center

- MAPS program, Institute for Bird Populations

- 2018 Arrowhead Bird Banding Summary – Superior National Forest (PDF)

- Hubachek Wilderness Research Center, University of Minnesota

- Hub’s Place – The Wilderness Research Center, Quetico Superior Wilderness News