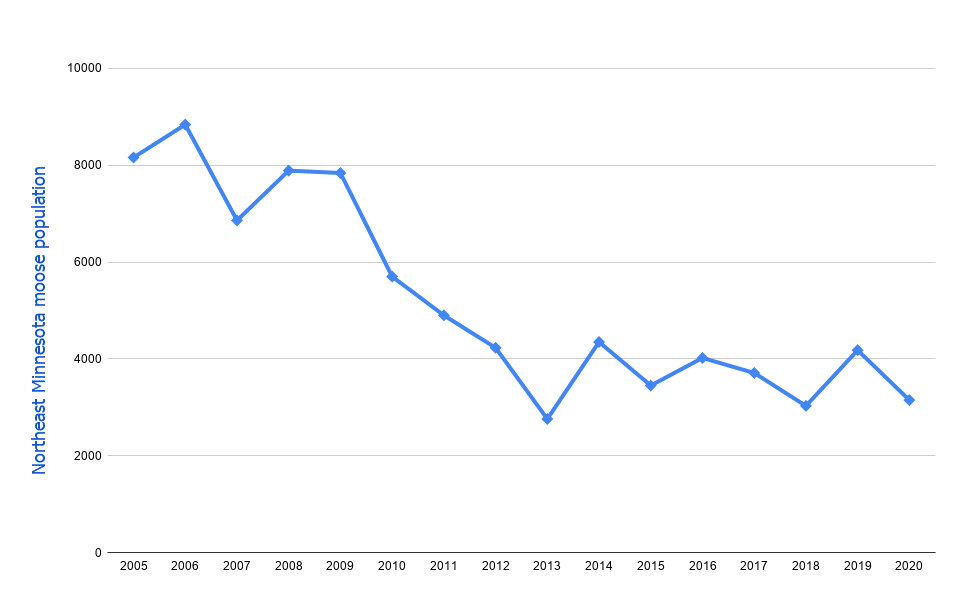

Wildlife managers in Minnesota have released their results from this winter’s aerial survey of the region’s moose population. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources estimates about 3,150 animals are living in the area — sharply down from the peak in the mid-2000s, but not significantly changed from the past several years.

“The stability itself is good news but it does not serve as evidence for either a turnaround or a continued decline in the population of Minnesota’s most iconic northwoods animal,” the agency says.

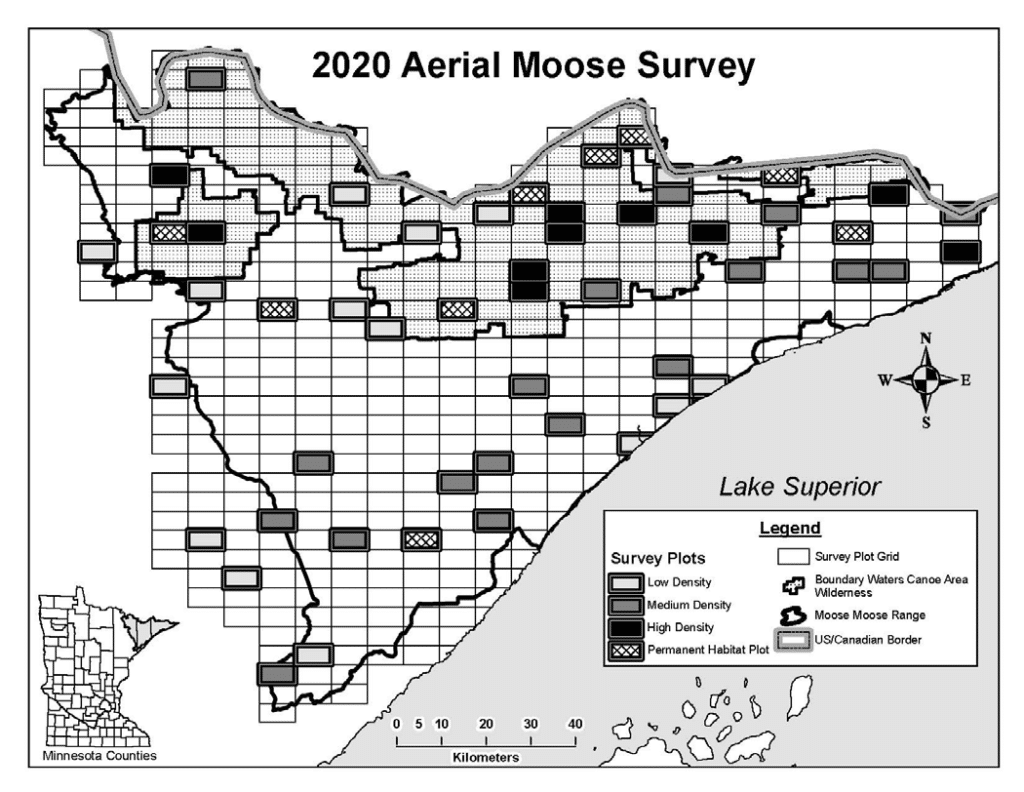

The survey was conducted with nine days of flying in DNR helicopters over the forests of northeastern Minnesota in the middle of January. The total moose range is 6,000 square miles, so it’s not possible to do an aerial survey of the whole region. Instead, the biologists looked at 52 plots that are each about 14 square miles. Crews flew eight routes over each plot, spaced about one-third of a mile apart, recording all moose they observed.

The highest density of moose were in areas in and near the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, with lower numbers farther south.

They factored in the density of vegetation and other factors affecting visibility, and analyzed the data to come up with an estimate for the entire range. But they emphasized that any year-to-year changes are not statistically significant, rather the ongoing survey helps managers understand ups and downs over decades.

“Statistical uncertainty inherent in aerial wildlife surveys can be quite large, even when surveying large, dark, relatively conspicuous animals such as moose against a white background during winter,” the researchers explained.

Comparing this year’s number to last year simply isn’t statistically valid. The data instead help the researchers see long-term trends. The biggest trend observed so far has been the steep drop in the population starting in 2006 and 2007, after a peak of more than 8,000 moose in the region. It reached what appears to be a “new normal,” for now, in about 2012, with the population hovering around 3,000.

That was the same year researchers added a new element to the study: nine plots that were home to changing forest, and would be surveyed each year. When designated, these “habitat plots” had either recently experienced or would soon experience wildfire, prescribed burning, or timber harvest.

It’s part of an “effort to better understand moose use of disturbed areas and evaluate the effect of forest disturbance on moose density over time.” While moose are thought to do well in areas of young forest where they can browse on nutritious young aspen and other species, it’s not as simple as cutting or burning more acres.

One key obstacle to the population growing again that has been identified is the survival rate of moose calves. The percent of moose mothers observed with calves has dropped from about half in 2005 to a third today.

“Our adult moose are surviving on par with North American numbers, maybe a little lower … but we’d really have to see calf survival increase, and for several years, for the population to start trending up,” Glenn DelGiudice of the DNR told the Duluth News Tribune.

Changes in habitat, whitetail deer, wolves, climate, and more forces comprise a population puzzle. The annual survey helps fit a few more pieces together.