These days, the pace in the Boundary Waters and Quetico is fairly slow. It’s a place of leisure, by and large, for today’s visitors. But for Ely’s Don Beland and Atikokan’s Joe Meany who raced across the wilderness during the days of the Ely-Atikokan Canoe Race, the pace was fast, the stakes were high, and the going was rough.

The roughly 200 mile event was also the backdrop for a hard-fought local rivalry between Ely guide, trapper, and outfitter Don Beland and Atikokan miner and, later, Quetico Ranger Joe Meany. The two would tangle most memorably in the 1964 event, the last of the races, when one would earn a hard-earned victory and the other would survive a frightening tumble down a waterfall that would destroy his canoe and nearly take his life.

More than 40 years after the classic contests, Beland and Meany, both retired and in their mid-seventies now, remember the details of their efforts with emotion and relish.

1962—the first race

A couple dozen teams entered—“It ain’t that I did those sort of races,” Beland remembers about entering the first Ely-Atikokan race in 1962. “I guided and trapped up here full time, so I guess this is what I do. A kid that worked for the Scout Base wanted to race, so we did it. We just wanted to beat the competition to the first portage, and after we did that we kind of, sort of, just kept on going.”

Beland and Barry Bain, a guide at the Summers Canoe Base, finished second in the inaugural event against well-known Twin Cities professional racers Gene Jensen and Irvin “Buzz” Peterson.

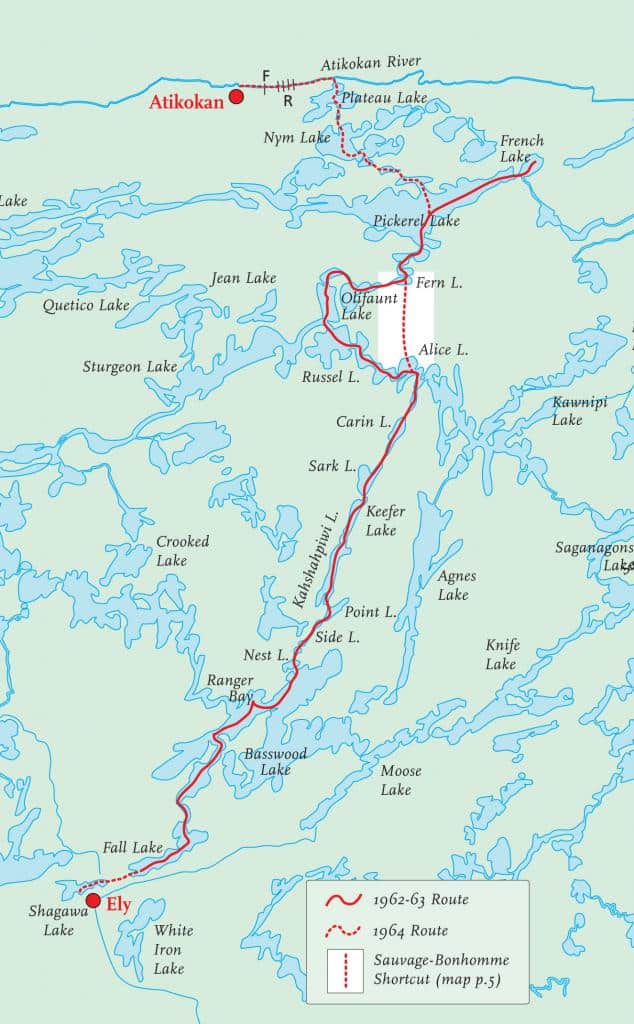

Early in the race, which started on Fall Lake, Jensen and Peterson made up the 30 minute stagger on Beland and Bain (racers started in heats every half hour) but chose to stay with the more knowledgeable local paddlers rather than rely on map and compass navigation. Through the heart of the Quetico the two teams paddled together along the most efficient route to Atikokan—from Ranger Bay of Basswood Lake, up to Kahshahpiwi, and then curving through a series of smaller lakes through Pickerel Lake to the finish on French Lake.

In Peterson and Jensen, who designed canoes and is credited with developing the bent-shaft paddle, you could catch a glimpse of the advances that were coming to recreational canoeing and canoe racing. The Twin Cities pair used laminated paddles, rather than the old “beaver” style used by Beland and Bain. While the Ely pair kneeled in the canoe and switched sides on a count, the Twin Cities team was seated and switched paddling sides before the boat turned, avoiding the costly steering strokes.

After an overnight rest interval in Atikokan—which Bain spent nursing severely blistered hands—the racers pointed their bows back toward Ely for the return leg. Peterson and Jensen were content, with their first-leg lead, to paddle along with Beland and Bain. Beland and Bain could have taken advantage of their rivals’ mistake at the forked portage that leads out of Kahshahpiwi Lake, but Bain chased down Peterson and Jensen to tell them they had gone the wrong way.

While Beland doubts if he and Bain could have out-paddled Peterson and Jensen from there, he lets on that he might have enjoyed the chance to try, if Bain would have let their two rivals stay lost.

In the end Peterson and Jensen won that initial contest, and the $1,000 first prize that attended it. Beland and Bain finished second and earned $500. According to Beland, most of the rest of the teams got lost on the out-going leg and finished well behind the leaders.

1963—a victory for Ely and Beland

The second running of the event—where paddlers would this time start in Atikokan, beat for Ely, and then return—began in stormy conditions. Both the weather and the mood prior to the competition were unsettled.

Beland and his new partner Ralph Sawyer of Michigan, the four-time winner at the time of the prestigious Au Sable River Canoe Marathon and a canoe and paddle maker himself, ended up competing with a borrowed boat after the one they paddled up to the race from Ely measured three inches longer than the allowable 18 feet. Beland and Sawyer quickly prepared to cut the canoe down and mend it with fiberglass—after they agreed to purchase it from the person they borrowed it from!—but were then informed such remodeling would not be allowed. Finally, late at night, they tracked down a damaged, 17-foot wood-canvas Chestnut that two Native American paddlers declined in favor of a seemingly less

efficient 15-footer.

The weather was wild at the start too. The racers were met by huge swells whipped up by strong winds from the west. Conditions were bad enough that Beland wondered if the race should even start as scheduled. It did, and according to Beland most of the 18 boats in the contest had swamped before making it to the first island on French Lake.

“The race was over in fifteen minutes,” Beland said. “I had a plan, though. I knew Pickerel was really going to be swelled, and we were going against it. We had to get down Pickerel, so the plan was every 500 feet to stop and dump the canoes. That’s how we made it down Pickerel.”

The race was essentially won there. The winds calmed in the evening—the race legs started in the late afternoon and most of the racing was done at night—and Beland and Sawyer had a relatively pleasurable trip to Ely. The pair did repairs to their boat in Ely, which had accumulated 30 extra pounds of weight due to torn canvas. The return leg to Atikokan was a veritable victory lap, their lead after the first day being so large. The pair took only 33 hours and 38 minutes to cover the distance and earn $1,000.

The victory eventually earned Beland a visit to New York and a spot on the game show “To Tell the Truth.” That happening was so big in Ely, children in school got to watch the show during the school day. On the program, where three contestants attempt to convince a celebrity panel that they are who they say they are, Beland convinced two of the four panelist that he was indeed Don Beland, the canoe racer from Ely, Minnesota.

“The other guys did their homework,” Beland acknowledged. “They went to the library and read up on canoeing. One of them was a brassiere salesman!” Not to be lost in the results of the 1963 race was Joe Meany and his partner Eugene Tetreault, a fellow iron miner. Competing in their first Ely-Atikokan race that year they finished 6th overall.

“I was first introduced to it when I saw those American professionals come up,” Meany explained thinking of Sawyer, Jensen, and Peterson. “I’d paddled canoes before, but never raced them. When I saw how they could move those canoes, I decided I better learn.”

Meany would prove to be a quick study.

1964—Atikokan’s Joe Meany wins; Beland survives

In what would prove to be the final race of the series, last minute changes to the course caused a pre-race stir just as the weather and Beland’s canoe problems did in 1963. The race that year would start and finish on the Ely side. The Ely organizers had moved their terminus to Shagawa Lake in Ely itself. Atikokan organizers wanted as much excitement for their town, so they moved their finish closer to town too, adding more distance, a long portage, a road crossing, and a scary run down the Atitkokan River which was peppered with whitewater.

“They changed the route at the last minute and said you had to go down the river,” Beland remembers. “Well, hell, we’d never been down the river. Nobody had been down the river, I don’t think, except them [Meany and Tetreault]. And there was rapids and waterfall on there.”

Adding to the controversy were the shortcut portages Meany’s team had cut in the Quetico. Beland remembers race rules allowing competitors to take any route between the start and finish, but forbidding the cutting of portages.

“Meany cut off a big arm of it by cutting portages down,” Beland said. “I never made a big deal out of it; I didn’t care. They probably worked for the Forest Service so what they did was probably legal. They just cut long portages that cut out about eight miles of paddling.”

Meany, who says he earned the nickname “Outlaw” from Beland over the incident, acknowledged having done “a lot of deking through the bush—cutting blind trails, things like that.” He contends there weren’t rules against such things and that it was all part of the gamesmanship of the wild race.

“You could go any which way you wanted—

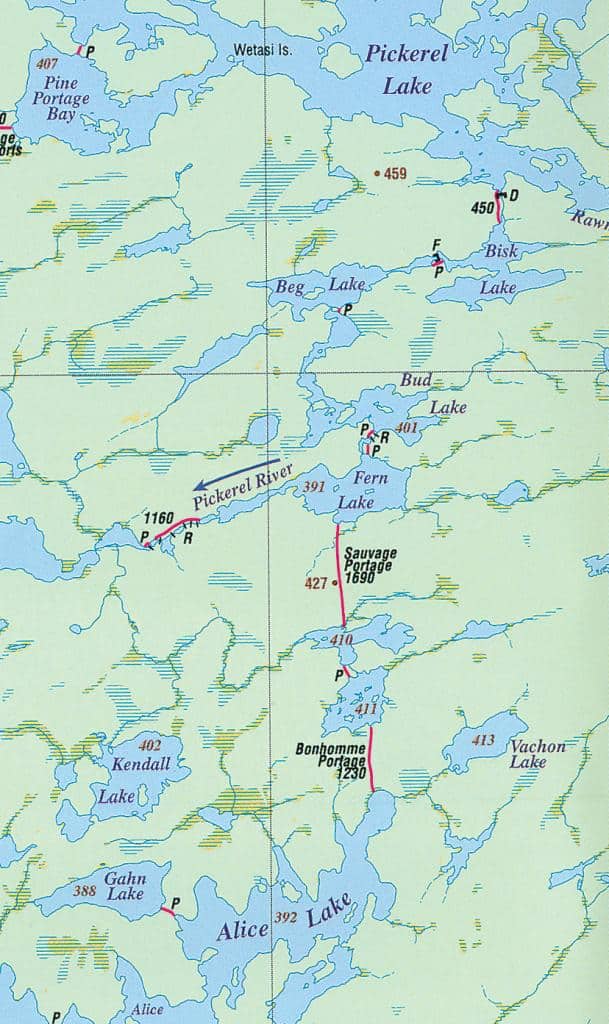

cut your own road if you wanted,” he said. “The

reason we won that race is because we cut two portages out of Fern Lake to two little lakes and from those lakes on to Alice Lake. It cut off a hell of a lot of water that we didn’t have to paddle.”

Meany, who was fondly nicknamed “Sauvage” by folks other than Beland, and Tetreault, called “Bonhomme,” hid their trails—which earned the same monikers—behind uncut swaths of forest so other racers wouldn’t find them first.

“We went in about fifty feet before we started cutting,” Meany enjoyed recounting today.

What might have been just a wonderful cat and mouse chase across Quetico-Superior country turned serious when Beland and his partner

that year, Carl Ketter, ran into trouble on the Atikokan River.

“I called the chairman and he said the falls and the rapids would be flagged during the day and [there would be] fires at night,” Beland remembers. “Well, I believed him. He sent a crew out to do it, but they never did it. I damn near got killed.”

Beland and Ketter paddled into a 15 foot waterfall. The canoe flipped in the bad water above the falls. Ketter was washed ashore before the drop, according to Beland, but Beland went over the ledge with the boat turning over him.

“If felt myself drop over the falls,” Beland recounts. “I said good-bye old world when I was in the rapids. They were deep with big boulders, and I was hitting the boulders and I thought I was going to get trapped underneath them.

You know how fast you can think sometimes.

I looked up and I could see the sky and I, honestly, I said good-bye old world.”

Beland, luckily, washed up on a reef in mid-stream. His boat was wrecked and he was bruised, if not broken. He couldn’t immediately get back to shore because of the fast water surrounding him.

“Getting banged up you didn’t know if you had broken arms or smashed ribs or what,” he said. “So I started examining, carefully, and I couldn’t find anything that wasn’t together.”

Meany and Tetrault went on to win the race, the last of its kind in the Quetico-Superior. Meany, who still jokes about needing to “beat them in the bush, not in the water” was no less adept with a paddle as he was with a brush axe. Later that same year and again in 1965 he and his brother Don, a well know paddle-maker in his own right, won the Canadian Professional Canoeing Championship, which was contested over a 33 mile course in Beardmore, Ontario.

The near-miss effectively ended Beland’s canoe racing career. He started to wonder, he said, “Where’s a nice 60 acres where a guy could buy a farm?”

Not that the long-time Ely resident stayed away from boats and water. He and his wife ran an outfitting business on Moose Lake for many years.

A Shared Camp on Lac La Croix

Visitors to the Lac La Croix Ranger Station during Meany’s term as ranger there may remember his “Looper Board,” a hall of fame for rugged paddlers who, in the spirit of the Ely-Atikokan race, tested their mettle against the clock on the Hunter’s Island loop. Meany and a partner paddled the circle route in 33 hours, 38 minutes, and 18 seconds when Meany was in his fifties. The recognized record is 28 hours, 49 minutes, seven seconds by Dan Litchfield and Steve Park.

But ol’ Don Beland has a comment on that. “Bob Olson and I did the loop in under 24 hours,” he deadpanned, paused, and then added “with a three-horse motor!”

“If they want to know the record, that’s what it is,” he laughed.

Beland and Meany got the opportunity to spend the better part of a week together at Lac La Croix a while back when Beland and his extended family made a trip through the area. Beland asked upon arriving at Lac La Croix, “Is there a Joe Meany around here someplace?” Meany, who’d been alerted to Beland’s arrival is said to have replied replied, “No, but there’s an Outlaw here!”

Beland said Meany convinced his family to stay at the ranger station and do day-trips from there, so the two Ely-Atikokan champions could reminisce about their days racing through the wilderness. The two even talked about paddling the length of the Mississippi together someday.

“It was a great race,” Beland said. “It was a celebration. It was a big deal, an international thing. The dinner was packed and the governor was there, so it was a big thing.”

“It’s too bad that it died, because it offered the whole nine yards.”

By Charlie Mahler, Wilderness News Contributor

This article appeared in Wilderness News Summer 2006