The iconic red pine forests of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness are no accident, say researchers. Tree rings, fire scars, tool marks suggest that the forest was created intentionally by Anishinaabe people during the height of the fur trade.

Evidence shows fire was used to develop preferential landscapes in heavily-traveled areas, particularly on lakes along the international border. Dr. Evan Larson of the University of Wisconsin and collaborators from the University of Minnesota recently published a peer-reviewed paper based on 15 years of field studies and analysis in the Boundary Waters, making the case for changes in wilderness management.

In an essay republished in Wilderness News in 2018 from the Minnesota Conservation Volunteer, Larson explained the technique of “dendrochronology.” His team matches up patterns of tree rings to reconstruct an exact history of a forest.

“Wide rings correspond to wet summers, and narrow rings to dry ones,” Larson wrote. “As weather and climate vary, uniform patterns emerge in the rings of trees across the region. Distinct as fingerprints, the patterns can be read to assign calendar dates to the rings of dead trees with absolute certainty.”

With centuries of tree ages and other data, important clues can be extracted. But first, the researchers needed to retrieve samples.

For three years early in the study, Larson and his collaborators canoed hundreds of miles through the Boundary Waters, using crosscut saws to take samples of dead trees, and hauled heavy portage packs full of the resinous wood out of the wilderness and back to the lab.

Reconstructing history

All the effort was apparently well worth it, because it has allowed an understanding of forest and fire history going back to before European arrival in the region.

By finding fire-scarred tree stumps and scarred trees that people once used for harvesting pitch, and by employing tree-ring analysis to date the evidence, the scientists have precisely described 527 years of fire history in the region. The work includes 75 study sites across the Boundary Waters. It builds on the pioneering work of famed forester and BWCAW advocate Miron ‘Bud’ Heinselman and the knowledge and traditions of Ojibwe people who still live in the region.

The researchers say the work has shown that fires were most frequent at specific sites along major travel routes, where indigenous people sought to create and preserve certain types of forest.

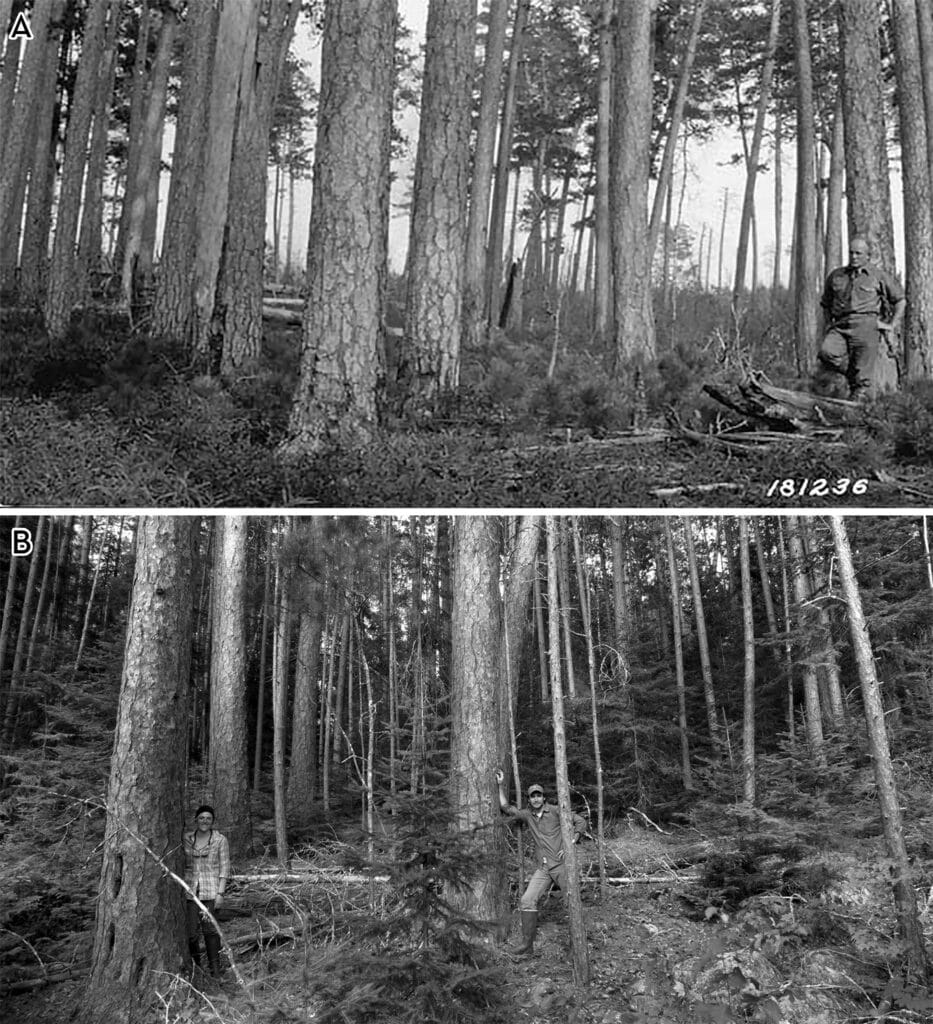

Mature red pine are fairly resistant to fire, as they usually lose their lower limbs and have thick bark, so a fire can do little harm. But frequent fires keep the understory clear, burning up species like balsam fir. The end effect is an airy forest dominated by the large trunks of red pines that could be 300 years old.

“Fire produces many environmental responses, including increased blueberry production, fewer ticks and flying insects, and more open, ventilated, and accessible forest conditions,” the paper states.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that modern visitors prefer the same sort of forest that indigenous people and fur traders sought. A survey of BWCAW users cited by the authors say “most modern wilderness visitors exhibited strong preferences” for camping at pine-studded sites.

Many of the sites bearing evidence of the most intensive use historically are designated wilderness campsites today, still affording the right location and conditions to make for an appealing stopping point.

Red pine provided a valuable resource for both Ojibwe people and French-Canadian fur traders: resin. Resin was mixed with animal fat and wood ash to create gum that sealed birchbark canoes.

Red pine produces the most resin of all the pine species in the Great Lakes. Evidence of encampments along the Border Route show large areas of red pine with the marks of years of resin harvesting. It was likely processed on the site and traded with passing canoeists.

Burning for a better forest

The work uncovered several sites along the Border Route where fire had apparently been an intense parts of its history. One such location on Lac La Croix had been burned 13 times between 1660 and 1890. Seventy trees in the area showed marks from being peeled for resin.

The analysis showed not only the frequency of fairly small, localized fires throughout the region during the fur trade era, but the almost complete halt at the beginning of the 20th century, when many indigenous people were removed from the land, and even natural fire began to be suppressed.

The result was a loss of iconic red pine stands.

“[T]he reduction of Anishinaabe land use practices, including fire use, coupled with wilderness designation has produced a more homogenous, densely forested landscape that is both more susceptible to catastrophic fires and less resilient to droughts when both disturbance processes are predicted to increase in frequency and severity in the future,” the paper states.

Ironically, the stands of big, old red pine with less understory growth, promoted by human-caused fires, became one of the defining images of the Boundary Waters wilderness and the push to have it designated as wilderness in the 1964 Wilderness Act.

Opportunity to lead

The scientists say the findings should be a “call to action” for advocates and wilderness managers to acknowledge this traditional knowledge and once again return frequent fire to the landscape, for the health and resiliency of the wilderness woods, and as an important step toward social justice.

“A unique opportunity exists in the BWCAW to showcase land management that acknowledges cultural history, ecological diversity, and the connections between people and environment,” the authors write.

The BWCAW is well-suited to lead the way in wilderness management. Because large parts of the Boundary Waters, especially along the famed Border Route, were never logged, the stumps and scars are still visible, and so is the forest that resulted. This is an invaluable historical record not available in many other places.

They say it’s time to engage indigenous people in understanding human connections to the land, and in ongoing management.

Indigenous knowledge has recently begun to be involved in prescribed fire in the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore in Lake Superior. A 2017 article from the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission described a new partnership between the National Park Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and U.S. Forest Service to burn rare pine habitat on Stockton Island. Local elders shared how people had long used fire to maintain prime blueberry-picking at the site.

The researchers say that restoring traditional fire practices in the Boundary Waters would ultimately create a safer and healthier forest — that would also be more resilient as the climate changes.

“Wilderness management must continue to be refined to more explicitly recognize the role of people in creating the pre–European American landscapes of North America,” the authors conclude, “the value of local and traditional knowledge in understanding ecological change, and the fundamental importance of engaging both Western and traditional knowledge systems to ensure that sustainable approaches to management are employed.”

Reference:

Evan R. Larson, Kurt F. Kipfmueller & Lane B. Johnson (2020) People, Fire, and Pine: Linking Human Agency and Landscape in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and Beyond, Annals of the American Association of Geographers

Note: All photos from paper, used with permission as per open access copyright

Editor’s Note: In this article and the reference article, the authors use Anishinaabe to refer to the cultural groups also referred to as Ojibwe or Chippewa but who refer to themselves as Anishinaabe (singular) or Anishinaabeg (plural). We recognize that in other instances the word might refer to other Indigenous groups whose ancestral lands span the Great Lakes region.

More information:

- What is Wilderness? Examining tree rings, researchers reconsider the history of human influence in the Boundary Waters – Evan Larson, Minnesota Conservation Volunteer

- Larson, former students co-author article in international journal – UW-Plateville

- Native fire management returns to Apostle Islands – Mazina’igan (PDF)