By Kevin Proescholdt

Many people would think that once Congress designates an area as wilderness, the area finally is safe and protected. At such a point, wilderness advocates could turn to other pressing matters, secure in the knowledge that that particular Wilderness has been protected forever.

Unfortunately, however, this rosy scenario usually doesn’t turn out as hoped. Wilderness conservationists documented the shortcomings of this wishful thinking with a report released in April entitled “Wilderness Between the Cracks: Where Motor Use and Other Wilderness Violations have Degraded the Eastern Part of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.”

The 20-page investigative report, conducted by the Izaak Walton League of America, Sierra Club North Star Chapter, Northeastern Minnesotans

for Wilderness, and Wilderness Watch, took over a year to complete.

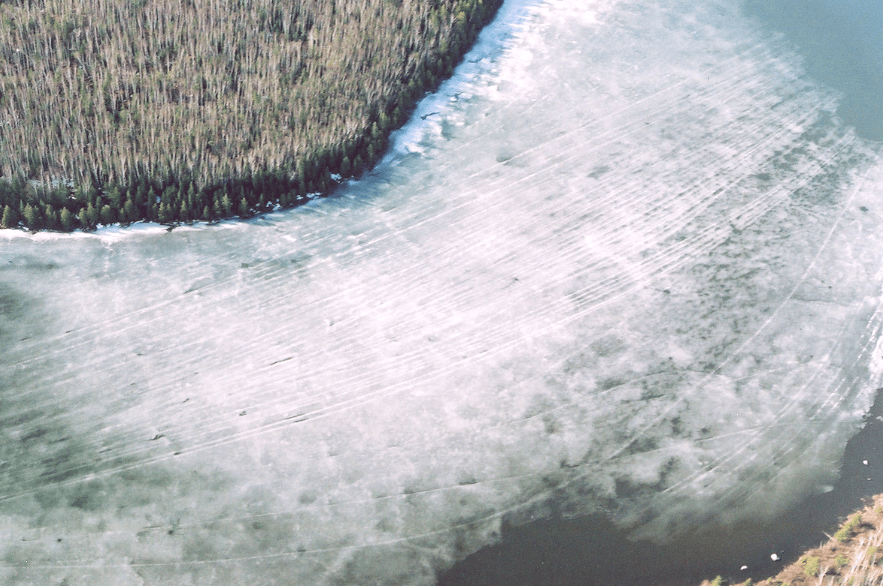

The report contains over twenty photographs that help document an extensive number of violations of wilderness laws and regulations in the eastern part of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) in northeastern Minnesota.

The 1.1-million-acre BWCAW is the most popular and most visited unit in the entire National Wilderness Preservation System. An original wilderness of that system under the 1964 Wilderness Act, that law unfortunately contained compromise provisions that singled out the BWCAW for continued logging and motorboat use. Congress passed new – though still

not yet complete – protections for the area in 1978 with the passage of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act, Public Law 95-495.

The 1978 bwca Wilderness Act eliminated logging in the area, tightly restricted mining, eliminated snowmobiling within the wilderness except for two short access routes for snowmobiles less than 40 inches in width, and reduced motorboat use from about 62% of the water surface area of the wilderness to about 21% today after a number of long phase-out provisions.

The report documents snowmobile violations on Saganaga Lake; the international border portages from South Lake eastward through Rat, Rose, Rove, Watap, Mountain, Moose Lakes to the Fowl Lakes; Stairway Portage; Pine and Clearwater Lakes; illegally-large outboards on the Fowl Lakes and Saganaga Lake; towboat problems on Saganaga; incursions of All-Terrain Vehicles (ATVs); and chainsaw use on international border portages. The full report can be read on the Izaak Walton League’s web site at http://www.iwla.org/publications/wilderness/wildernessbtwcracks.pdf.

Among the many disturbing findings of the report is the lack of enforcement of the 40-inch regulation for snowmobiles on the Saganaga Corridor. The 1978 law allowed snowmobile access on the corridor on Saganaga, but only for snowmobiles that were less than 40 inches in width. This was an effort by Congress to limit the growth of snowmobiles to sizes only manufactured in 1978, and to try to minimize the degradation to wilderness values by allowing only smaller machines. Unfortunately, the Forest Service has rarely, if ever, enforced this provision, and virtually all of the snowmobiles that now drive this route north into Canada exceed 40 inches in width.

In recent years, wilderness advocates became aware that snowmobiling had continued within the BWCAW – illegally – on another trail called the Tilbury Trail between McFarland Lake and North Fowl Lake near the end of the Arrowhead Trail north of Hovland, Minnesota.

Though the trail had been used prior to passage of the 1978 bwca Wilderness Act, the use of motorized vehicles on the portion of the trail within the BWCAW became illegal in 1978. Yet snowmobiling continued on this trail for another 25 years, until the Gunflint Ranger District of the U.S. Forest Service discovered the trail. Snowmobilers still used the Tilbury Trail for several years after this discovery despite barricades and signs erected by the agency. As an outgrowth of that issue, the same conservation organizations became curious about the existence of other uses or activities within the eastern portion of the BWCAW that might also violate wilderness regulations. “Wilderness Between the Cracks” was the result of their investigations.

The four wilderness organizations recognize that law enforcement in a designated wilderness is a challenging endeavor for the Forest Service, complicated by lack of easy accessibility, declining budgets and personnel, incomplete understanding of wilderness regulations at all levels of

the agency, and other agency priorities. Forest Service Law Enforcement personnel are stretched thin and often pulled away from the Superior National Forest to help deal with other pressing enforcement or emergency activities. The Superior National Forest budget, for example, sustained another cut in Recreation, Wilderness, and Heritage for FY 2007. Such cuts provide continuing challenges for proper wilderness stewardship of the BWCAW.

Further complicating the BWCAW law enforcement picture is the presence of U.S. Border Patrol agents along the international border. The Border Patrol, part of the Department of Homeland Security, has been exempted from complying with most laws in some of the recent homeland security laws passed by. Among the laws from which the Border Patrol is exempted are the 1964 Wilderness Act and the 1978 bwca Wilderness Act.

As a result, Border Patrol officers can legally utilize snowmobiles and other motorized travel within the BWCAW. Some of the snowmobile tracks documented in this report may indeed have come from Border Patrol activities, though the wilderness advocacy organizations still believe that illegal recreational snowmobile activity accounted for at least some of

the tracks within the BWCAW.

While the photos in this report came from 2006 and cannot assist in real-time enforcement, the four groups believe nonetheless that many of the photos depict areas of recurring violations. They hope that this report will assist the U.S. Forest Service in targeting its enforcement activities and so enhance the agency’s wilderness stewardship of this precious area. They believe that the Forest Service shares their concern that protecting the bwca Wilderness shouldn’t fall “between the cracks” in the agency’s many other functions.

Kevin Proescholdt directs the Izaak Walton League of America’s Wilderness and Public Lands Program. Kevin helped pass the 1978 bwca Wilderness Act and was the lead author of the 1995 book, Troubled Waters: The Fight for the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act, the story of that struggle.

This article appeared in Wilderness News Summer 2007