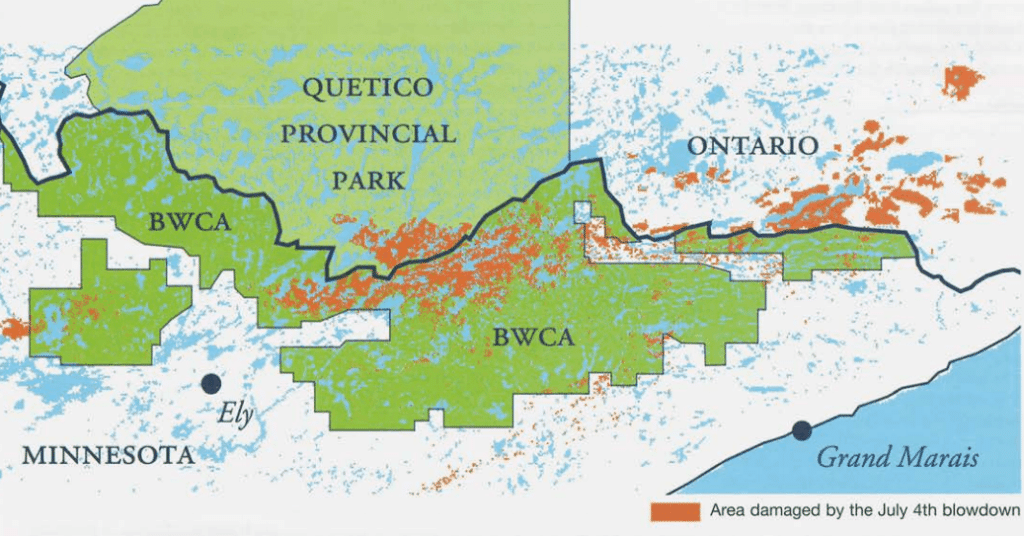

On July 4, 1999, the sky fell. Or so it seemed. The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness was hit by a historic storm unlike anyone had ever seen. As dark inky clouds rolled in, winds roared, flattening large swaths of trees, some over 200 years old. The storm wreaked havoc on the region for nearly 24 hours, ultimately altering 500,000 acres.

Cary J. Griffith, the author of Gunflint Falling, dives deep into the harrowing and courageous stories that unfolded on that humid summer day.

Multiple witnesses observed the tempest quickly approaching from the west, stirring up whitecaps on the lakes. People reported that interconnected trees “were being lifted up and out of the ground and set back down”. Throughout the book, different perspectives recount the fear and confusion that ensued, including a group of canoeists—some visiting the wilderness for the first time—who were directly hit by the intense winds.

Voices from the Blowdown

The book features numerous personal accounts, providing a comprehensive look at all that transpired in the event. Outfitters, guides, pilots, emergency and forest personnel, along with campers in the direct line of the storm, share personal recollections of their experiences. Wilderness trippers sit hunkered down in tents, anxiously waiting for the storm to pass while listening to trees fall.

“While they struggled to keep the tent anchored, they heard the sickening sound of the tree being pulled up by its roots, starting to topple. There was an interminable moment while the maelstrom howled and the tree, as though in slow motion, continued to fall. And then it pounded down on top of them…flattening the paper-thin walls” and causing injuries to the three women inside.

The book details the scope of the emergency response as crews coordinated and implemented rescue efforts. Pilots from different agencies systematically searched campsites, portages, and bodies of water for those in need of help.

Outfitters and guides took to motorized boats, searching lakes, and evacuating the injured. Folks stuck along wilderness roads continuously got out of their vehicles to move debris.

Storm of the century

Throughout the book, there are descriptions of the meteorological events and reports that transpired that day. The storm, which built strength in the Dakotas, had forecasters reporting possible thunderstorms throughout northern Minnesota. Some thought it would be a storm commonly seen in the summer. Others knew the heat and humidity were especially unusual, even for northern Minnesota.

However, as the day progressed, the atmosphere changed, causing what Griffith describes as a derecho; one “unparalleled in the annals of known meteorological history”. A derecho is associated with a fast-moving group of severe thunderstorms, known as a mesoscale convective system. Because of their strength, these systems tend to be widespread and long-lived. In the case of the 1999 storm, it was unprecedented to have this type of wind event at that latitude.

Griffith goes on to share how the storm bore its full wrath on the quiet, northern wilderness, with winds exceeding 100 miles an hour, leveling the forest. First responders, along with teams from the USFS – Superior National Forest, were burdened with changing conditions and information. The complexity of the emergency initiated a level of Type II incident response, managed at the state level using existing state resources.

Aftermath

The book highlights the unprecedented conditions the responders were facing. The USFS created a document that approved the use of motors and some mechanized equipment. Knowing there were thousands of visitors in the wilderness, allowed for a quicker response from search and rescue.

Nearly 25 years later, those who venture into the BWCA still can see the impacts of the storm. With dead and dying pines littering acres of forest floor, the region remains susceptible to forest fires. The blowdown would set the stage for future wilderness events like the Cavity Fire of 2006, the Ham Lake Fire of 2007, and the Pagami Creek Fire of 2011. Yet as the ending of the book notes, forest regeneration from the blowdown is still happening years later.

An engaging analysis

Those interested in the Quetico Superior region will appreciate the detailed maps and incident documents within the book. Both do a concise job of demonstrating the breadth of destruction that the blowdown encapsulated.

In Gunflint Falling, author Cary Griffith examines the events and stories that occurred before, during, and after the blowdown. He shares the heroic and selfless actions of both public and private citizens. The conclusion seems to be that no one can predict whether a storm like it will happen again in northern Minnesota. Climate change continues to impact the region. As a result, the author seeks to unravel some of the meteorological complexities that the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness experienced on that hot summer day.

More information:

- Gunflint Falling by Cary J. Griffith

- Fourth of July marks 20th anniversary of Boundary Waters Blowdown

- July 4-5, 1999 Derecho

Wilderness guide and outdoorswoman Pam Wright has been exploring wild places since her youth. Remaining curious, she has navigated remote lakes in Canada by canoe, backpacked some of the highest mountains in the Sierra Nevada, and completed a thru-hike of the Superior Hiking Trail. Her professional roles include working as a wilderness guide in northern Minnesota and providing online education for outdoor enthusiasts.