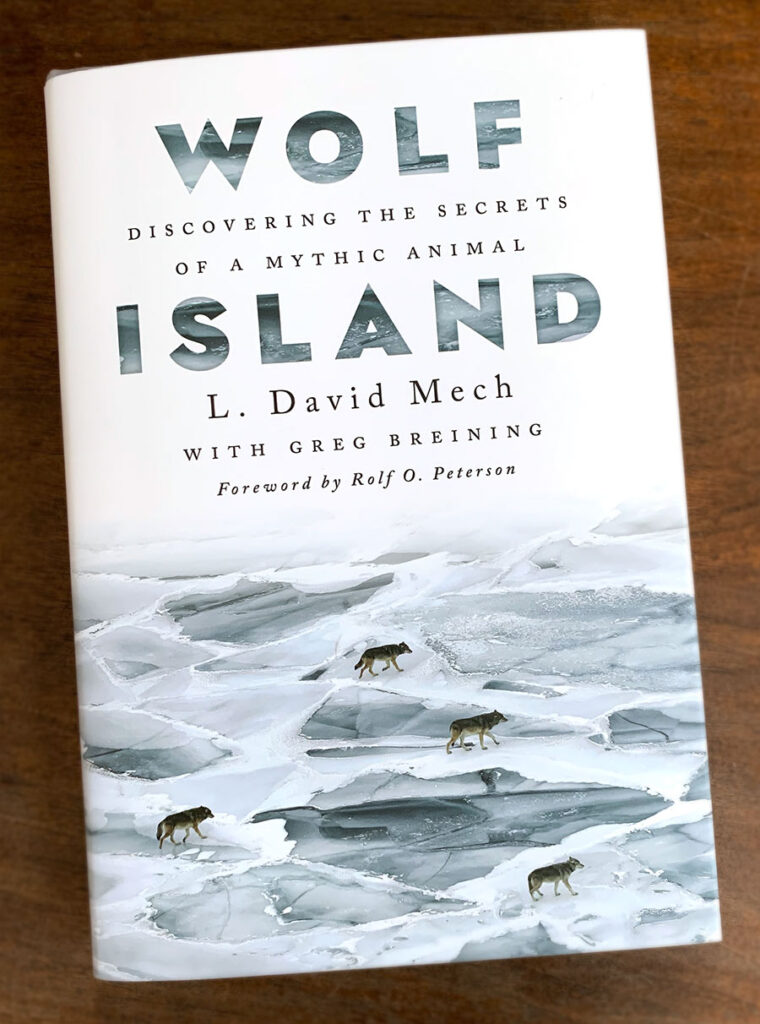

L. David Mech with Greg Breining

Foreword by Rolf O. Peterson

University of Minnesota Press

One of the joys and demands in the life of a wildlife biologist is the time spent in the field collecting data and observing the subject matter firsthand. In the case of wolf research scientist L. David Mech, for three consecutive years between 1958-1961, he was elated to study the predator-prey relationship between the wolves and moose populations on Isle Royale in Lake Superior. Wolf Island – Discovering the Secrets of a Mythic Animal is his colorful chronicle of daily life as a graduate student on the island with the wolves, the moose, trusted pilots, supportive neighbors and his family. These initial efforts kickstarted what is now known as one of the longest and internationally renowned ecological studies of the wolf population in North America.

The book begins with a dramatic opening scene: a large moose staving off a pack of wolves; one who is chomping at its nose, another ripping into its throat, while others tear at its rear. It tries to escape – kicking them off whenever possible – but too much blood loss causes it to lose steam. Down it falls and the pack clamors onto it.

Not every aspect of studying wolves culminates in this type of daily drama. However, this memoir captures a truly unique and adventurous way of life for this young biologist starting a new predator-prey study of wolves. Living on an island accessible only by boat or plane, young David learns the wilderness and terrain as he begins to search for clues and patterns of the wolves’ behavior. During this time, he meets his neighbors who are primarily old commercial fishing families and National Park Service colleagues, remotely living across 210-square miles of forests and shoreline. With each mention, the reader senses how vital they are to the author’s survival.

This force of nature and wilderness is integral in Mech’s pursuit of science.

Mech recalls how careful planning was required. His ability to return home at the end of the day when traveling by boat was determined by the will of the weather on Lake Superior. It was crucial to pack a sleeping bag on every plane ride – should the plane malfunction or the radio go down, it could be days before someone could find them. Overnight supplies were stored near lean-tos along the trails in anticipation of any obstacles on the ground.

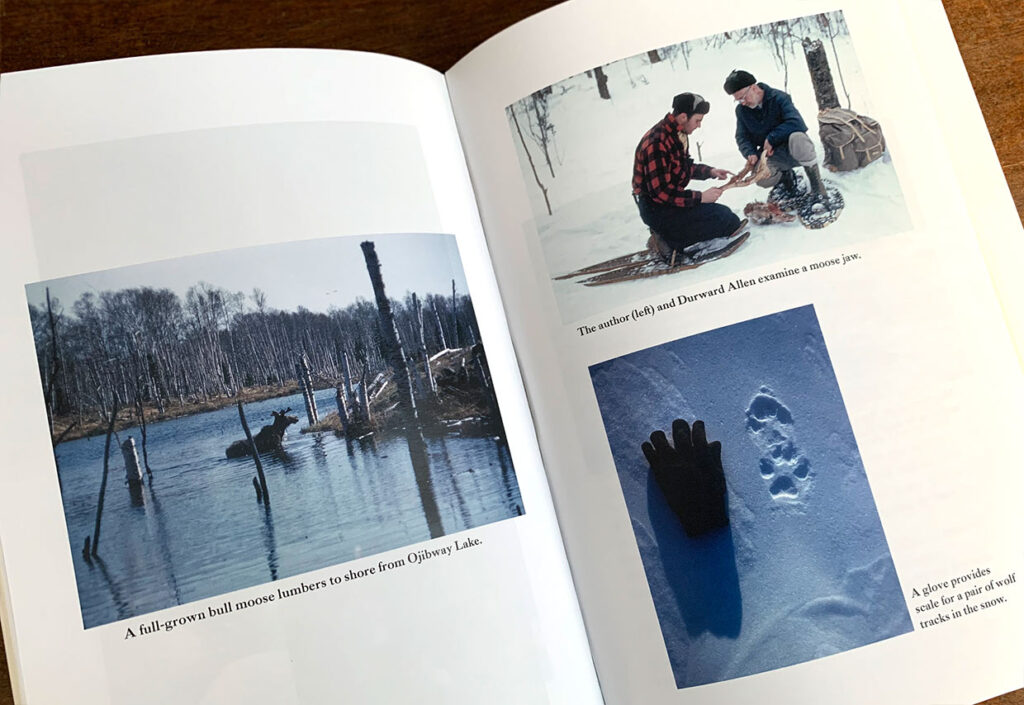

From initial daily collections of wolf scat to determine its diet, to hundreds of plane rides and hikes through the wilderness, Mech learns a great deal about the iconic grey wolf. During his time on the island, the number of wolves inhabiting Isle Royale remained between 21 and 22.

As the studies progressed, Mech describes how aerial views from a chartered plane with dedicated pilots improved the quality and frequency of the observations immensely.

The wolves’ patterns and behaviors became much more observable. He could find wolf dens, watch their social behavior, and see how wolves travelled in lines with two or three bringing up the end and one lone wolf trailing behind. It became apparent that there was not an alpha wolf, more, an equal distribution of most able members in the pack. They could see the moose populations throughout the island and how the wolves selected their target and positioned themselves before attacking a moose and her calve, downwind, from various positions. He could observe which habitat and conditions were better suited for the moose to survive. Mech’s memoir, written with Greg Breining, illuminates the genesis of what is now the longest running prey-predator study. The research continues today after six decades. It has become a model for wildlife biologists worldwide. The book is dedicated to the key pilot, Donald E. Murray, who committed twenty years of his life to this particular study.

Since 1958, when Dr. Durward Allen of Purdue University selected L. David Mech as his top choice to initiate this study on wolves, the research has been validated scientifically on many levels.

Except for instances when Lake Superior freezes over, providing an ice bridge from the mainland, Isle Royale is detached and isolated. With a significant population of moose already living on the island, the new wolf population that crossed over from the mainland in the late 1940s created an ideally controlled ecological laboratory. It was a prime opportunity to study the wolves’ predatory relationship with their sole prey on the island, the moose. No other large prey were present there. As the moose were the wolves’ sole prey, one would surmise their eventual demise. However it was documented that the wolves’ successful kill rate was a mere eight percent.

Counting, tracking and watching the wolves to see how they behaved socially and interacted with the moose, offered invaluable new insight into this species.

As technology has progressed in recent years, GIS, collar-banding and mapping has helped make the study even more informative. This important research has continued for decades under the auspices of biologist Rolf Peterson, of Michigan Technological University. This is an important read for budding wildlife biologists and anyone interested in the survival of species.

Book Review by Anne Queenan