The continued hot and dry weather gripping the Quetico-Superior region is affecting water and wildlife.

The first two months of meteorological summer have been the hottest and driest spells since the Dust Bowl era in the 1930s. All of northern Minnesota is currently in either “severe” or “extreme” drought, according to the National Drought Monitor.

Extremely dry conditions has led to several wildfires and caused authorities to institute fire bans, and the drought is having other deleterious effects. Rivers are running out of water, lakes are warming, and fish are suffering.

“For most sites, rainfall has been less than half of the average monthly rainfall for both May and June,” the National Weather Service recently reported about northeastern Minnesota. “A fairly dry fall and winter with below normal snowfall preconditioned the current drought.”

Low water levels

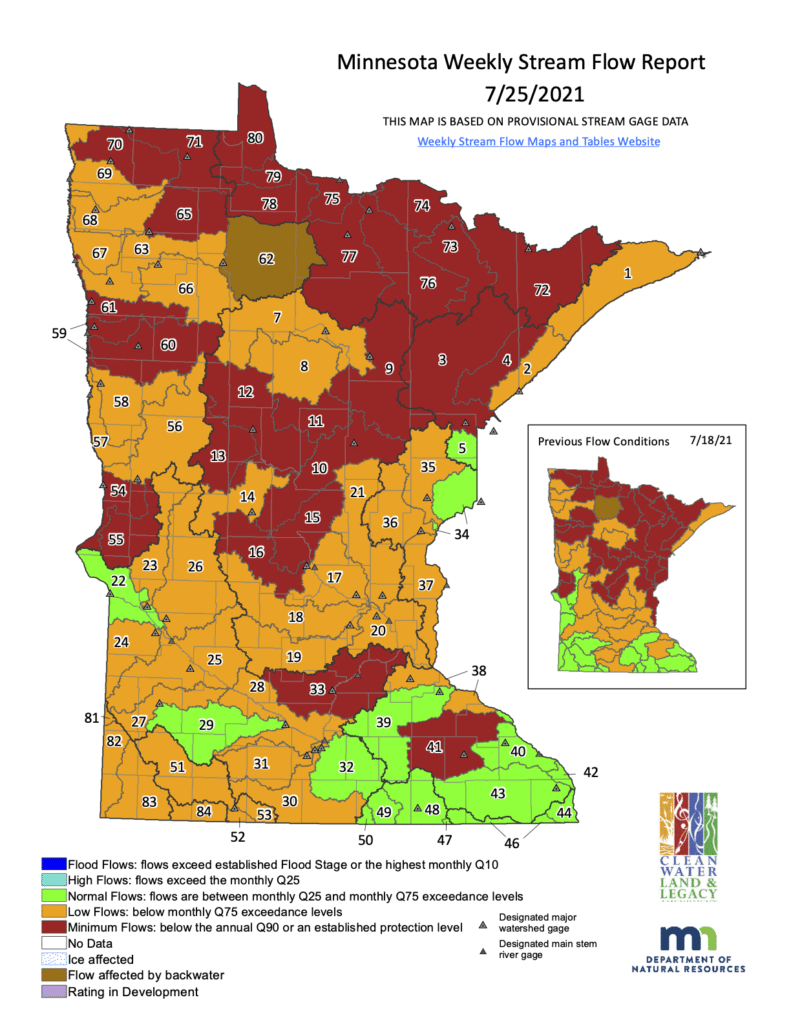

On the North Shore of Lake Superior, rivers fed primarily by rain and runoff are feared to be drying up. The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources reports that North Shore rivers are in “low” flow stage, while the rest of the Arrowhead region is even worse, at “minimum flows.”

By August, popular Gooseberry Falls near Two Harbors could dry up entirely, according to assistant park manager Nick Hoffman in the Star Tribune. The last time that happened was about 15 years ago.

Meanwhile, on many lakes, low water is making it hard for boaters to launch. The DNR reports some water bodies have dropped so far that the concrete launch ramps no longer extend all the way into the water. Officials encourage boaters to check ramps and water levels before attempting to launch, and finding somewhere else to go if necessary.

Dry conditions have also resulted in some stretches of North Shore rivers drying up, leaving isolated pools of water. Being stranded in warming water can kill fish outright, or the conditions can prevent movement and migration necessary for spawning and returning to Lake Superior.

The DNR has temporarily suspended some surface water appropriation permits in the St. Louis River watershed as a response to flows dropping below levels defined in the state’s drought plan.

Fish fry

With changes in water levels and temperatures come challenges for the fish that call lakes and rivers home. In lakes, fish species that need cold, oxygen-rich waters are threatened by warm weather, while river and stream species are also dealing with those issues, and loss of habitat.

When the water temperature is in the 70s, most of the region’s fish go dormant, according to Grand Marais Area Fisheries Supervisor Steve Persons. He recently talked with WTIP about how the heat affects the stream trout species — brook, rainbow, and brown trout, and splake — that are stocked in many lakes in northern Minnesota.

“In most cases it really just puts an end to their feeding, their growth drops off, the larger fish are affected more in that way than smaller fish,” he recently told WTIP.

Native coldwater fish species like lake trout and cisco also feel the pressure from heat. The fish spend the summer in the deepest, coldest part of their lakes. But if the warm surface water continues into fall, it could affect their growth.

Most fish should make it through, but Persons said his concern is more long-term than one hot summer. If droughts become more frequent, it could reduce the amount of suitable habitat for some species, and affect the population. He said it’s still okay to fish in the heat, but suggested anglers not try catch-and-release for too many fish. The fish are often stressed by fighting in warm waters, so he recommended taking what anglers want to eat and calling it a day.

Water quality concerns

While hot weather can be harmful to fish, it’s exactly what cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, need to thrive. As water levels drop and become clearer during drought, sunlight can shine deeper in the water, letting these native, ancient organisms bloom en masse.

Cyanobacteria often appear like spilled green paint on water, and produce toxic byproducts. These chemicals in the water have been blamed for at least 20 dog deaths in Minnesota in recent years, and can also affect human health.

“What algae like are hot, dry, calm conditions. They’re an organism that likes hanging out on the surface of water and have perfect conditions for growth,” Pam Anderson, manager of MPCA’s surface water monitoring, told Bring Me The News in June. “So most lakes have available food in them — phosphorus, the nutrient that’s hanging out in our lakes — but when we get a lot of sun and a lot of hot temperatures, that’s when these harmful algal blooms really thrive.”

Such blooms are usually associated with southern Minnesota, while northern waters have been cold and unproductive enough to prevent significant blooms. But cyanobacteria toxins have been detected in the past in Boundary Waters lakes. Voyageurs National Park has also experienced blue-green algae blooms in part of Kabetogama Lake.

It’s not easy to tell if something is cyanobacteria, and if there are toxins in the water. Officials encourage water users, “When in doubt, stay out.”

Tree troubles

The drought impact on northern Minnesota’s forests are perhaps most visible. The numerous wildfires now burning in the area are a result of low humidity and dry wood. Trees need a lot of water to grow and thrive, and when they don’t get it, become stressed. Not only does this create fuel for fires, it makes the trees more susceptible to insects and disease.

“Most native insect pests and pathogens are opportunists,” Brian Schwingle, central region forest health specialist for the DNR, told the Star Tribune. “They don’t cause problems unless trees are stressed.”

Large swaths of the region’s forests that are thick with balsam fir, and many are dead or dying because of an outbreak of spruce budworm.

A 2014 report on climate change impacts on Minnesota’s forests from the U.S. Forest Service predicted drought conditions would not just raise the risk of wildfires, but that more frequent blowdowns, pest outbreaks, and drought stress could create more fuel. While the fire-dependent boreal ecosystem could benefit from more fire, too much could hamper regeneration, ultimately leading the transition to more grassland and barrens.

Climate change connections

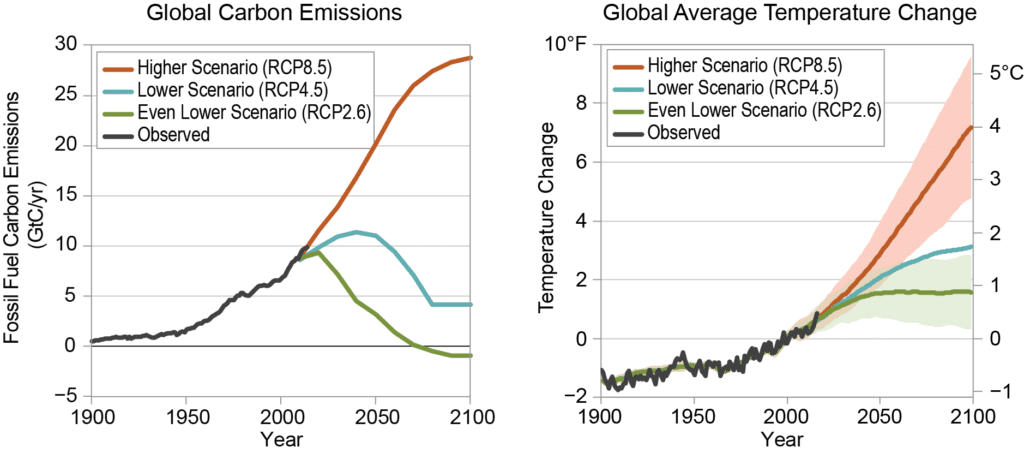

The world’s climate is always changing, so no single weather event can be attributed directly to global warming. But, droughts are expected to occur more frequently as the world continues to warm. This warming has been linked by scientific research to fossil fuels and carbon emissions in the atmosphere. Climate forecasts for northern Minnesota predict more dramatic swings in weather, from intense storms and rainfall, and long periods of drought. This summer is a sign of what’s to come, some scientists say.

“The question on my mind is will the drought years become more common and get to a point where it’s the new normal,” Diana Karwan, a hydrologist and associate professor at the University of Minnesota, told the Star Tribune.

Minnesota has always seen periods of drought, but usually short-lived. The region’s ecosystem has adapted to this pattern, but long-term changes could cause significant permanent impacts.

“It’s over the fullness of time when we start to see this kind of summer happening more and more frequently that we have to look hard at how long we can sustain a trout fishery in these lakes, particularly the shallow lakes,” Grand Marais fishery manager Steve Persons told WTIP.

The drought is far from done at this point. The region would need at least three to five inches of rain over two weeks to recover, and meteorologists are not optimistic for this summer.

More information

- Are the drought’s effects on Gooseberry Falls a sign of bigger problems for North Shore waterways? – Star Tribune

- Trout in Cook County and the BWCA feeling the heat in 2021 – WTIP

- Heat wave leads to early reports of blue-green algae on some Minnesota lakes – Bring Me The News

- Blue-green algae: If in doubt, stay out – MPCA

- Foresters brace for brutal fire season as drought adds to threat to Minnesota’s trees – Star Tribune

- Drought in Minnesota – Minnesota DNR