Middle row: Chief Justice Lorie S. Gildea, Associate Justice Natalie E. Hudson, Evan Mulholland (MCEA), Emily Schilling (MPCA)

Bottom row: Jay Johnson (PolyMet), Associate Justice G. Barry Anderson

This week, the Minnesota Supreme Court considered a key question in the controversial PolyMet copper-nickel mine proposal: Is the company trying a bait-and-switch?

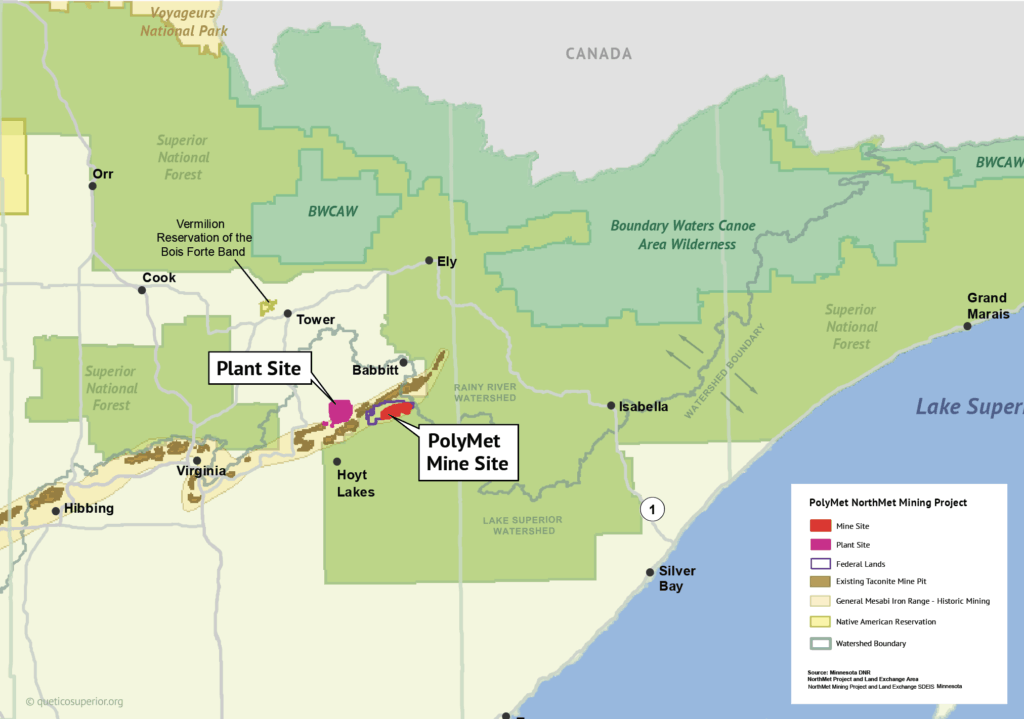

The mine received permits in 2018, and environmental groups have challenged many of the decisions in court. Now those lawsuits are working their way into the highest halls of justice. Decisions made in the near future could decide the fate of the project, which opponents fear would pollute water, air, and more in the St. Louis River headwaters region.

In the latest chapter, lawyers from the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy (MCEA), representing the nonprofit organization and partners, argued on Thursday that the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) should do more work on PolyMet’s air permit to consider if the company is being honest about its true intentions.

The Minnesota Court of Appeals agreed with MCEA in March, but PolyMet and the state agency appealed to the highest court in the state. MCEA is also representing Friends of the Boundary Waters Wilderness, Sierra Club, Center for Biological Diversity, and the Fond Du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

The issue of PolyMet’s real plans for the project arose in questions about the mine proposal’s air emissions permit, issued by the MPCA. The permit analyzed PolyMet’s expected discharges on the basis of its stated plans to extract 32,000 tons of ore per day. At that level, it is considered a “minor source” under the Clean Air Act, with looser regulations than larger operations.

But MCEA has pointed out that documents provided to investors, and analysis of mining investment standards, show PolyMet would be much more profitable if it extracted and processed 3.5 times as much rock. At such a higher level, the mine and the processing facility would trigger “major source” rules, requiring the company to invest more in reducing emissions of air pollutants.

“MPCA cannot issue a synthetic minor permit if, shortly after issuance, the permittee will seek to expand its operation beyond the limits, i.e., issue a ‘sham permit,'” MCEA stated in its brief to the Supreme Court.

The Environmental Protection Agency has guidelines for dealing with possible “sham permits,” in which a company tries to get a permit that’s not based on its actual plans. The MPCA says it followed those guidelines, but MCEA argued there was little evidence it did, and no factual findings included in its decision that explained how the agency analyzed PolyMet intentions.

In a one-hour hearing held online due to concerns about the coronavirus pandemic, lawyers from MCEA, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, and PolyMet argued their cases and took questions from six of the state’s seven Supreme Court justices. (Justice Paul Thissen was recused.)

“Under the Clean Air Act, whether a synthetic minor permit is a sham is a foundation question, and requires determination of intent at time of permitting,” MCEA attorney Evan Mulholland told the court.

Ten days after public comment closed on PolyMet’s air emissions permit in March 2018, the company published a new technical report required by Canadian financial regulators. The documents showed how the mine would make a lot more money at a larger scale.

Additionally, MCEA argued that the return-on-investment for the proposed project would be about 10 percent, but mining industry standards for investment usually seek a 30 percent ROI. That higher level of profitability would only be possible if the company produced more ore.

“There’s evidence that not only are they looking at expansion, there’s evidence that their current project is barely economic,” Mulholland said.

The attorney said that if global copper prices drop by even 10 percent, the mine as currently proposed may not be able to turn a profit.

PolyMet plans to use the former LTV Steel plant to process its ore. The plant has capacity to crush 100,000 tons of ore per day, but PolyMet has told environmental regulators it will only use one-third of that capacity. Meanwhile, according to MCEA, it’s been telling investors that it’s actively considering a much larger operation that could take full advantage of the plant’s capacity.

MCEA sent the documents and information to the Pollution Control Agency, but the agency rejected it as speculation. The environmental groups said the agency should have investigated the possibility of a sham permit and providing findings of fact about why it wasn’t an issue.

“Here, the PCA did not address the sham permit issue at all in its order, its official findings, its response to comments or in the permit itself,” Mulholland said.

The Court of Appeals said MPCA should essentially reopen the air permit and do more work, rather than the other option of overturning the permit altogether. After the regulators and the mining company appealed, the MCEA asked the Supreme Court to affirm the lower court’s decision.

In a Minnesota Supreme Court hearing last month, MCEA was once again arguing against permits issued by the state. October’s hearing was over challenges to to the project’s dam safety permit, for the large berms that will have to hold back massive amounts of liquid waste, and the permit to mine. The water discharge permit is also headed back to the Court of Appeals after a district court hearing.

The Supreme Court is expected to take several months to issue opinions on the lawsuits.

More information:

- Air Pollution Permit – Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy

- MCEA Brief to Supreme Court (PDF)

- Watch the hearing – Minnesota Judicial Branch

- Minnesota Supreme Court weighs PolyMet air permits – Duluth News Tribune