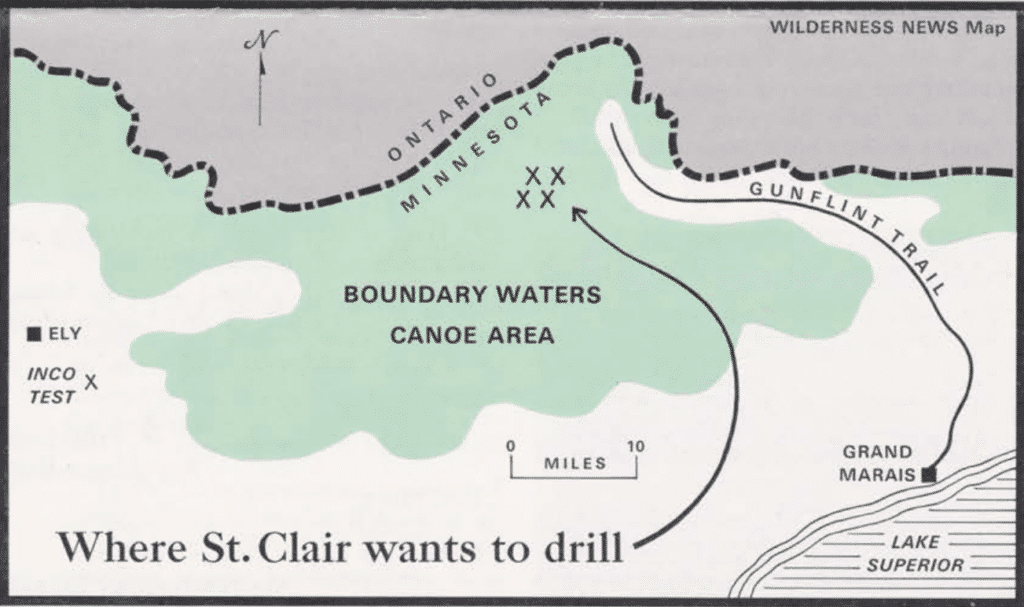

In the late 1960s, one man tried to install mining rigs inside the newly defined Boundary Waters Canoe Area. George St. Clair from New York had inherited underground mineral rights from his grandfather, and his actions set off battles in the courts and the newspapers, from MN to Washington DC.

Copper, nickel, and other precious metals have been locked in the rocks of northern Minnesota for more than a billion years. They have been of special interest to humans for about the past 70 years. Modern mine proposals in the region are the subject of much debate. Worries of polluted waters and despoiled public lands compete with powerful mining companies and job-seekers.

The PolyMet proposal in the headwaters of the St. Louis River has received permits, but courts have been rejecting them pretty rapidly over the past few months — much more remains to be decided before any hope of putting a shovel in the ground. Meanwhile, Twin Metals recently submitted a formal proposal for an underground mine along the South Kawishiwi River, upstream of the Boundary Waters. The Twin Metals proposal is tied up in the courts because of disagreement over the leases it holds for publicly-owned mineral rights. Those leases date back to the 1960s.

While some parts of the public and their elected officials have fought vigorously for the mines to be allowed, others have poured their energy into stopping the proposals. It’s a new chapter in a long story.

Historic connections

In the 1960s and 1970s, around the same time the Boundary Waters was protected as a federal Wilderness Area, when Voyageurs National Park was being created, when logging was coming to an end in Quetico Provincial Park in Ontario, there were also simmering fights over copper-nickel mining.

Just like today, wilderness advocates resisted the efforts. The proposals ultimately failed due to a combination of factors, including lawsuits, legislation, mineral prices, and simple twists of fate.

The Quetico-Superior Foundation, formed in 1946, launched its new quarterly newsletter Wilderness News in 1964 — the same year the federal Wilderness Act was signed into law. Many back issues of Wilderness News are available to view in our archives. Five decades later, we dove into past issues to see what’s different now, and what’s the same.

‘The St. Clair Affair’

No-one today is proposing to mine inside the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness — the 1.1 million acres of federally-protected wilderness that is part of the Superior National Forest. But the Twin Metals proposal is just a couple miles from the southern edge of the wilderness, near the Little Gabbro entry point.

In 1969, one man tried to dig inside the wilderness itself. George St. Clair’s efforts may have been largely an attempt to establish his legal ownership rights, not necessarily operating a mine, but it was seen as a major threat no matter his motivation.

“A drilling contractor of Jackson Heights, N.Y. (Queens) and Mexico City, St. Clair had informed the U.S. Forest Service that early this winter he intended to install rigs on part of the 30,000 acres in the BWCA to which he had inherited underground mineral rights from his grandfather, George A. St. Clair, oldtime Mesabi pioneer,” Wilderness News editor Philip Kobbe wrote in the winter 1970 issue.

St. Clair’s focus was in an area “a dozen roadless miles from the end of the Gunflint Trail,” around Gabimichigami, Gillis, and other nearby lakes. Geologists had reported finding nickel in surface rocks in the area.

The Wilderness Act had been passed in 1964, which included the Boundary Waters, but left notable exemptions for logging and other extractive industries in Minnesota’s flagship wilderness. St. Clair wanted to prove he had the right to seek minerals, perhaps only so the federal government would have to compensate him for their value if he couldn’t exercise the rights.

Familiar fight

The response was multi-faceted, showing many of the same strategies used to fight mine proposals today. Wilderness advocates took to the courts, the press, the public, the state legislature, and ultimately, Congress, to stop St. Clair — and prevent any chance of future mining inside the wilderness boundaries.

The U.S. Forest Service was the first line of defense. The agency confiscated drilling equipment that St. Clair’s survey crews had cached in the BWCA, and said “We will be there physically to stop him.”

The Izaak Walton League led the legal fight, filing suit in U.S. district court in Duluth. Judge Philip Neville heard the case. The closely-watched case somewhat fizzled when St. Clair failed to show up for a highly-anticipated hearing.

“When it developed that U.S. marshals had been unable to put a finger on St. Clair, Judge Neville observed, ‘It is not in accordance with our American system of justice to pass judgment on a man until he has been duly notified of the charges against him,'” Wilderness News reported. “This pronouncement appeared to forestall further legal action — at least for the time being.”

The press’s interest was piqued, with papers around the state weighing in on the issue. Wilderness News quotes several prominent newspapers calling for drilling to be stopped — but acknowledging the government may need to buy out St. Clair.

“Mr. St. Clair has all the appearance of a poker player dabbling with the pot to see how large the payoff can be coaxed,” wrote columnist Jim Klobuchar, Ely native and father of now-Senator Amy Klobuchar. “It could well be that the government will have to make some out-of-court settlement.”

Legislators take notice

Around the same time as the attempted Duluth hearing, legislators in St. Paul were also discussing mineral rights in the BWCA. The state owned about 100,000 acres of rights in canoe country. Some elected officials saw it as a possible windfall, while others thought they could be used to help settle the issue with St. Clair.

Duluth Senator Raymond Higgins told a meeting of the state senate’s Public Domain Committee that the state should assess the value of its holdings — perhaps to seek compensation from the federal government.

“They could be worth millions to the state,” he said. Wilderness News noted that “it was later reported Higgins himself holds inherited mineral rights to 117 acres in the BWCA.”

Two mining proponents testified at a Jan. 26 hearing, advocating for the state to immediately begin surveying its holdings in the BWCA to determine their value.

Another northern Minnesota Senator had a different idea. Future governor of Minnesota, Senator Rudy Perpich of Hibbing, thought the state could help deal with St. Clair. Perpich “suggested that the state trade its mineral rights outside the BWCAW for those held inside by individuals such as George St. Clair.”

As such, Perpich requested a special session of the legislature to “block the treasure hunt,” and said emerging consumer advocate (and future presidential candidate) Ralph Nader might want to get involved.

From court to Congress

About two years later, Judge Philip Neville eventually ruled against St. Clair. Wilderness News reported that Neville issued a permanent injunction against mining in the BWCA.

“Mineral development by its very definition cannot take place in a wilderness area; else it is no longer a wilderness area,” Neville wrote in his ruling.

Even the New York Times reported on the decision, noting that Neville’s injunction “prohibits any assistance by the United States Department of Agriculture, the National Forest Service or state officials in any attempt to exploit the minerals.”

“The St. Clair Affair” seemed settled, but proved premature. Another two years later, in 1974, the Eighth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Neville’s decision. By this time, both St. Clair and Judge Neville had passed away. “The appellate court’s reversal of the injunction directed the Forest Service to determine whether an exploratory permit should be granted upon proper application,” Wilderness News reported. “This decision places the added responsibility on the Forest Service of deciding whether or not to grant exploration and mining permits to commercial mining interests.”

With the courts essentially punting the issue to the agency, attention turned to the U.S. Congress.

D.C. decides

There were several reasons wilderness advocates were interested in new federal legislation to increase wilderness protections for the BWCA. There was opposition to continued logging, motorboats, snowmobiles, and motorized portages.

When Congress finally passed in 1978 the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act, it attempted to find compromises and solutions to many of those points of conflict. There was also a lot of language about mining.

A Mining Protection Area was included, which prohibited mining on certain lands on the edge of the wilderness. Road corridors for the Echo Trail, Fernberg Road, and Gunflint Trail comprised most of it.

The law also made almost any chance of mining within the wilderness proper impossible. The bill explicitly prohibited mining of any federally-owned mineral rights in the BWCAW, nor even using “property owned by the United States in relation to any mining of or exploration for minerals in such areas which may materially impair the wilderness qualities of the wilderness area.”

For cases like those of the late George St. Clair, the Secretary of Agriculture was authorized to acquire any privately-owned mineral rights within the wilderness. But the legislation also included several factors to consider when trying to determine a fair price.

The Secretary of Agriculture was to determine if the mineral rights had been acquired fraudulently, as was often the case with historic rights. Many mineral rights were claimed during the 19th century under the authority of laws like the Homestead Act of 1962 that were designed to “put settlers on the land.” Rights weren’t eligible if they had been separated from their surface rights after 1927, when the Forest Service designated the area as roadless, which had essentially made mining impossible. Rights could even be declared fraudulent if someone who had previously owned the rights was a known land speculator.

In the face of such regulation and restriction, there were no more murmurings about trying to mine inside the BWCA. But the minerals are still there throughout the region, and interest is once again focused on the interconnected fates of mining and the canoe country wilderness.

MORE INFORMATION:

Read the Winter 1970 issue of Wilderness News (PDF)

Book: Troubled Waters: The Fight for the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, by Kevin Proescholdt

North Star Press of St. Cloud, 1995