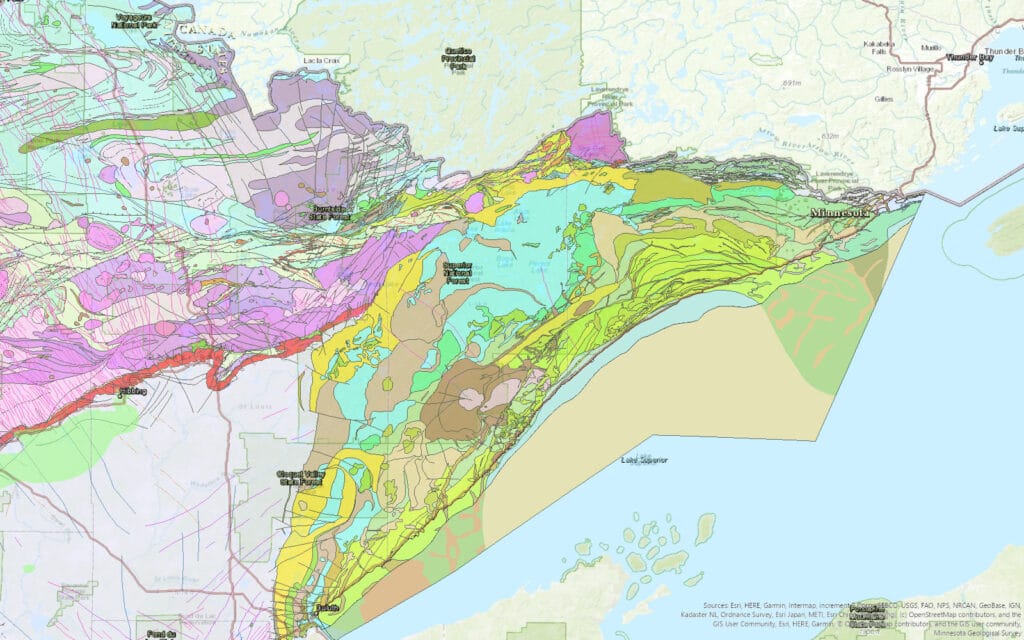

The ancient rock of Minnesota’s North Shore of Lake Superior and areas inland is being carefully studied by state surveyors. Minnesota Geological Survey staff spent this summer working in Cook County to map and describe the billion-year-old bedrock and glacial deposits that cover it in some places.

Most of the shoreline of Lake Superior reveals the raw basalt bedrock that underpins the rugged scenery. Inland, mixed with ancient lava, there is more rock that emerged into existing volcanic rock. It makes for a complex tangle of very hard rock.

“The work entails going into the woods, into the bush, along lake shores, wherever we need to go, to find places where the bedrock is exposed at the surface,” Terry Boerboom of the Minnesota Geological Survey recently told WTIP. “That way we can see what the rock is and start putting pieces of the puzzle together.”

Near Grand Marais, the geologists have been able to map individual lava flows visible on the surface, despite the fact they formed more than one billion years ago.

One part of the puzzle in Cook County so far is that most drinking water wells primarily have groundwater that moves through cracks and fissures in the bedrock. That’s because the rock is impermeable, with no water soaking through it slowly and getting filtered, but rather flowing through gaps that allow quick travel from from the surface to the well bottom 200 feet below.

This means drinking water can be easily contaminated with septic system discharge, or other pollutants. Increased knowledge of the groundwater will help keep water and waste separate.

The mapping could also help answer another question that has caused problems for property-owners and well-drillers: many wells have high salt content.

“We don’t really know what’s controlling that, we’re hoping that we can map saline wells and figure out why, look for patterns,” Boerboom told WTIP.

Better understanding of bedrock groundwater flows could also be important to assessing pollution risks from proposed copper-nickel mines in the region. The fractured bedrock and easy mobility of contaminated water has been a key concern regarding both the PolyMet and Twin Metals proposals.

A report by a hydrogeologist commissioned by the Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters in 2018 pointed out that there is some evidence of highly-fractured rock in the Twin Metals ore deposit. The water level in a nearby well had fluctuated up to two feet in a short time.

“This demonstrates that within the area of the well, the bedrock has sufficient conductivity to allow percolation to reach deeply within the bedrock,” wrote Dr. Tom Myers. “Water levels rise in a fractured rock aquifer only if there are connections among significant portions of the aquifer.”

More detailed maps of bedrock could help show the amount of water flow through the rock, and where it could end up.

The geologic survey is in progress in all three northeastern Minnesota counties. Ultimately, a County Geologic Atlas will be published, with maps and other resources. Working with the Department of Natural Resources, the effort will also result in maps of aquifers — including depth, flow, chemistry, and vulnerability to pollution.

One analysis of water samples from wells is to detect a radioactive isotope that was only released into Earth’s atmosphere during the decades when nuclear testing was taking place. Tritium’s presence in groundwater indicates the water came there from the surface at some point since the first atomic bombs were let loose. In other places, groundwater can be thousands of years old.

These tools will help local governments, soil and water districts, property-owners, businesses, and the general public understand the region’s water and rock.

Bedrock mapping is a priority across the state, as Minnesota is increasingly concerned about its groundwater. “County Geologic Atlases provide information essential to sustainable management of groundwater resources, for applications such as monitoring, water allocation, permitting, remediation, and well construction,” the agency says.

In 2013, a strategic plan for the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund prioritized completing county geologic atlases for the entire state by 2020. The decision doubled the speed at which the Minnesota Geologic Survey could operate.

In addition to field surveys, the initiative largely depends on private well records. This data can provide valuable insights into what is deep under the surface. Part of the survey includes ensuring well locations are accurately recorded.

So far, the survey has completed geologic atlases for 45 counties, just over half of Minnesota’s 87 counties. Cook County is currently one of 23 underway.

Once northeastern Minnesota’s surveys are complete, maps and data will be freely available to download on the Minnesota Geological Survey website. Printed copies will also be available for a small fee.

More information