A Vision of Preservation

The Quetico Superior Region has long been identified as an exceptional example of lake land wilderness. The vision of the region as a protected wilderness originated as early as the start of the 20th Century. Christopher C. Andrews, a Minnesota Forestry Commissioner who persuaded the General Land Office to withdraw 641,000 acres of land from public sale between 1902 and 1905. A 1905 canoe trip along the international border at the age of 77 then inspired Andrews to propose an international forest reserve. His work helped inspire the creation of both Quetico Park in Canada and Superior National Forest in the U.S. in 1909.

The establishment of Superior National Forest instigated a public land use debate that has continued throughout the last century as citizens and government have struggled to find an environmentally responsible balance between commercial development, recreational use and wilderness preservation.

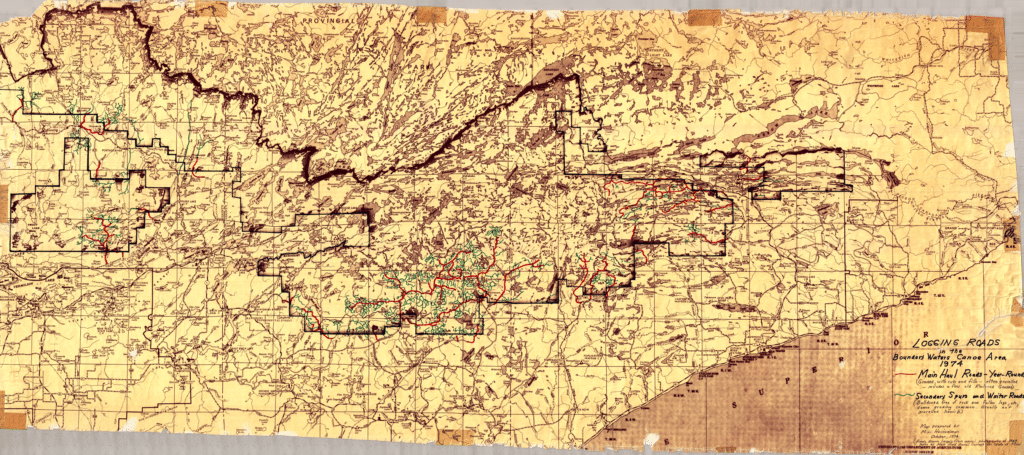

From 1919-1922 Arthur Carhart of the U.S. Forest Service developed the first recreation plan for Superior National Forest, favoring primitive recreation. A subsequent proposal to build several roads in Quetico Superior sparked the first national debate over the area’s use, weighing wilderness protection against recreation, tourism and timber production.

The resulting 1926 Forest Service policy established a wilderness tract eventually called the Superior Roadless Area. It allowed no new roads and no recreational developments other than “waterway and portage improvements.” It was the first policy to place equal importance on land use for primitive recreation and commercial interests.

A History of Land Use and Controversy

In 1925 lumberman Edward Backus submitted a proposal to the International Joint Commission to dam the Rainy Lake Watershed to produce electrical power, lumber and paper. The plan would have raised water levels as much as 80 ft. in parts of what are now Voyageurs National Park and the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. Ernest Oberholtzer, a wilderness explorer with intimate knowledge of the region, opposed the plan with the help of lawyer Sewell Tyng and a group of advocates from Minneapolis, including Frank Hubachek, Charles Kelly and Frederick Winston.

Oberholtzer’s efforts resulted in the formation of the Quetico Superior Council, through which he helped pass the 1930 Shipstead-Newton-Nolan Act. The Act prohibited homesteading, the sale of federal land, alteration of natural water levels, and logging within 400 feet of shoreline in the border lakes region.

The 1940s brought rapid growth in the boundary waters resort industry. By 1948, a total of 41 resorts had been built on the interior of the BWCA. Environmentalists realized that this development was jeopardizing the future of the area as a wilderness. Large scale land acquisition efforts began by the federal government and private organizations. In the end, 350 separate tracts of land were purchased and returned to their natural state.

Responding to the use of the border lakes by floatplanes, activists including Sigurd Olson, Charles Kelly and F.B. Hubachek mobilized and convinced President Truman to establish an air space reservation over the BWCA. The executive order, signed in 1949, prevented the landing of airplanes by both the general public and by private landowners.

The first regulation of motorboats in the BWCA occurred in 1948 under a U.S. Forest Service management plan which called for boats to be restricted to areas where their use was well established. Snowmobiles, which were considered “winter motor boats” first came to the BWCA in 1950 and by 1962 snowmobile use had become significant.

Motorized or mechanical portages in the BWCA were first used at railroad logging portages, and trucks were later used by resort owners to transport boats. Motorized portages, boats and snowmobile use would later become heated issues.

The Wilderness Act of 1964 and The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act of 1978

In 1964 Minnesota Senator Hubert Humphrey was instrumental in passing the federal Wilderness Act, which incorporated the BWCAW into the National Wilderness System as the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. Congress recognized the importance of protecting this unique canoe country wilderness, which not only is the largest wilderness area east of the Rockies, but has become the most widely used.

The 1964 Act prohibited the use of motorboats and snowmobiles within wilderness areas, with exceptions for areas where use was well established within the BWCAW. For Congress and the public, the Boundary Waters continued to represent a challenge. Although the Wilderness Act had directed the U.S.Forest Service to protect the primitive character of the area, it did not totally ban motorboats or snowmobiles—uses which were in conflict with fundamental goals of the Wilderness Act.

The next major legislation to be proposed, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act of 1978, sought to resolve the lingering issues of motorboat use, number of motorboats, motorized portages, the size of motors, and the use of snowmobiles. The final version of the Act was a compromise agreement between two citizen groups. The opposing groups were lead by Charles Dayton, a representative of environmental groups, and Ron Walls, a representative of northern Minnesota pro-motor groups. President Carter signed the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act into law on October 21, 1978.

The 1978 Wilderness Act was intended to resolve many of the issues of contention once and for all, and to bring quiet to nearly 75 years of land-use and recreation controversy.

In the nearly twenty years since the Act was passed, administrative rulings and judicial decisions have clarified issues such as limiting the number of visitors and the size of groups, the use and number of motorboats, the use of snowmobiles for trail grooming, and the use of motorized portages. One of the most recent rulings had to do with motorized portages. In July, 1993, the U.S. Supreme Court let stand a lower court ruling that required Four Mile Portage, Prairie Portage and the portage between Lake Vermillion and Trout Lake be closed to motor vehicles.

1996: A Flurry of Proposed Wilderness Legislation

The BWCAW and portions of Voyageurs closed to motorized use amounts to only two percent of the 84,000 square miles that lie within Minnesota’s borders.

In 1996, 8th District (northeastern Minnesota) Congressman James Oberstar and U.S. Senator Rod Grams (Minnesota) introduced bills (h.r.3880 and s.1738) in the U.S. Congress that would have returned motorized transportation to three BWCA portages, increased the motorized water surface area of the BWCAW from about 21 percent to about 31 percent, and created a “management council,” consisting primarily of local persons, to guide BWCAW issues. Congressman Oberstar and Senator Grams also introduced legislation that would establish local management council for Voyageurs National Park and remove all restrictions on snowmobiles, motorboats, and floatplanes in the park.

These bills were challenged by Congressman Bruce Vento’s Minnesota National Treasures Conservation and Protection Act (h.r.3470) that proposed adding 14,000 acres to the BWCA wilderness, limiting or closing motorboat access to three lakes in the BWCAW, extending the aircraft prohibitions to include the new land additions, and adding 78,000 acres of the Kabetogama Peninsula to the Federal Wilderness Area in Voyageurs.

President Clinton threatened to veto the Omnibus Parks Bill if pro-motor BWCAW legislation was included. This threat stopped the measures introduced by Congressman Oberstar and Senator Grams to attach their bills to the Omnibus Parks Bill. Congress adjourned without passing the Oberstar, Grams or Vento bills introduced in 1996.

The 1996-1997 Mediation Process Reaches Impasse

Two mediation efforts, one concerning the BWCA and the other Voyageurs National Park, concluded after nine months of meetings without resolution. After the 1996 Congress failed to pass Voyageurs National Park’s legislation, a 13 member panel representing various groups was appointed to resolve the conflict between motorized recreation and protection of the natural resources through means of mediated dispute resolution. The panel began meeting in August of 1996 and met every other week for most of nine months.

After using almost 20 meeting days it ended with 10 of 12 members supporting Draft 7, a six-point compromise that offered first-time stability for management of Voyageurs National Park. However, the mediation process required consensus to pass agreements. Two of the appointed groups, Citizen’s Council for Voyageurs National Park (CCVNP) and the Minnesota United Snowmobile Association (MNUSA), refused to condone a compromise resulting in the groups adjournment without an agreement.

Likewise, a Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness mediation process, conducted by Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service (FMCS) also began in August at the request of Senator Wellstone. The mediation process continued through the winter and spring with the various representatives offering more than a dozen major proposals in an effort to resolve some of the major motorized use issues. The mediation process concluded at its final session on April 28th without compromise or resolution on motorized use issues, truck traffic on wilderness portages or change in motorboat lakes.

1998 – Today

The challenge of maintaining the wilderness character of the region continues today. Motorized use continues to be debated through the legislative and judicial process. A 1998 transportation bill rider re-opened Trout and Prairie Portage to truck traffic, while closing Alder and Canoe Lakes to motorboats. In addition, ongoing litigation from the 1993 management plan resulted in a 1999 ruling that the Forest Service regulate motor use on the Chain of Lakes in accordance with the 1978 BWCAW Act. A later recalculation to increase annual day use motor permits was challenged, and a federal appeals court rejected the recalculation in 2006. Controversy has also arisen over a proposed snowmobile trail outside of the Boundary Waters that is visible from Royal Lake; it is under appeal in the federal district court.

Significant natural weather and fire events have also created new management concerns. On July 4, 1999, storms caused serious damage to nearly 400,000 acres (over 600 square miles) of forests in and around the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. An estimated 30 million trees were downed—many fell to the ground, but a portion remained jackknifed in the air, drying in the sun and creating conditions for a potentially catastrophic fire.

In an unprecedented interagency effort, the Forest Service worked with the Minnesota Incident Command System, local communities and fire experts to address the fire risk. The resulting response plan focused on reducing fuel, preventing fire, fire suppression preparedness and emergency response preparedness. The Forest Service began actively reducing the fuel load in fall 1999 by logging downed trees outside of the BWCAW and in 2001 began prescribed burns within and without of the protected area. As of December 2007 over 63,000 acres of blowdown had been treated, including over 43,000 acres of strategically located burn sites in the BWCAW selected to reduce fuel load and prevent the spread of fire.

Some of the burn sites did prevent the eastward spread of the Cavity Lake Fire of July 2006, which burned over 31,000 acres off the end of the Gunflint Trail. The largest fire in the BWCAW since 1894, it was followed closely by the Ham Lake Fire of May, 2007, which burned over 36,000 acres off the Gunflint Trail and 40,000 acres in Ontario. With only a few miles and a couple of months of growing season between them, they were the equivalent of one large fire.

The Gunflint Trail region has already begun to regenerate but fire risk continues. The Forest Service continues to make efforts to further reduce the fuel load and work with outfitters and local communities to educate visitors on fire prevention.

The challenge of maintaining the wilderness character of the region continues today.

– R. Newell Searle

Sigurd Olson, 1959

Sewell T. Tyng and Ernest C. Oberholtzer, 1925

Photographs from the book Saving Quetico-Superior, A Land Set Apart