A beloved magazine published by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources is turning 80 this year. The Minnesota Conservation Volunteer highlights many stories from the Boundary Waters and surrounding region, and Quetico Superior Wilderness News celebrates this contribution the state’s natural resources literature.

First published in 1940, the Conservation Volunteer has traced the arc of Minnesota’s history of managing and protecting its abundant natural resources. The lake country of northeastern Minnesota has been featured prominently in the coverage. Here we share a few excerpts from over the years.

Moose matters

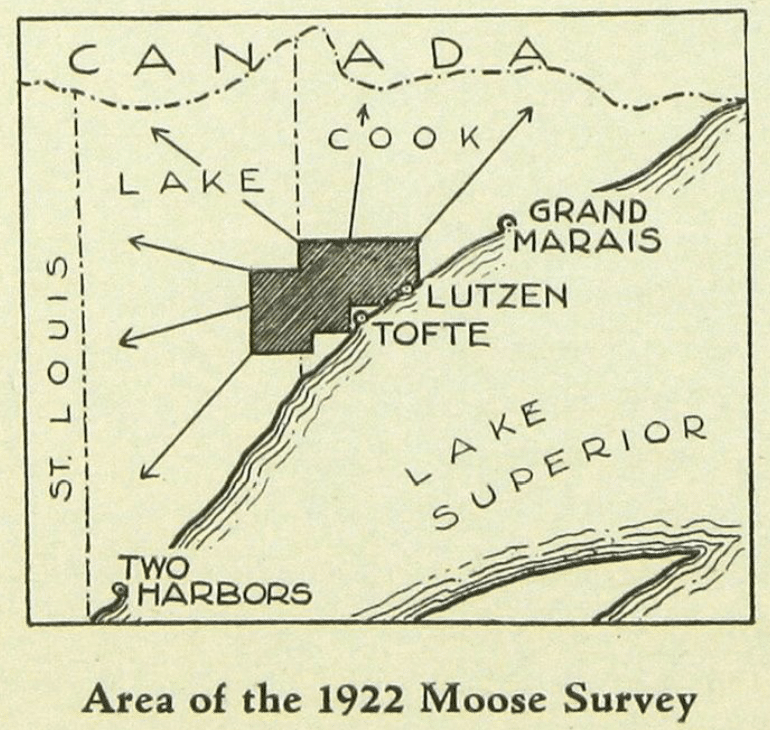

The very first issue of the Volunteer included a feature about the iconic species of the north woods: the moose. A renowned biologist and advisor to the DNR’s precursor, Thaddeus Surber, shared a report he wrote in 1922 about moose observations in Cook County. He then compared its observations to more recent knowledge.

“That the bulls at this season become ugly tempered and might, with very little provocation, even attack man, was shown by a little experience we had at this time. We pitched our tent in the Honeymoon Trail on the bank of the Temperance River September 27 and shortly after dark a bull visited us and roared, bellowed and thrashed the brush with his antlers for nearly half an hour before finally leaving; he paid no attention whatever to two revolver shots fired into the air, and at one time we feared he would really attack us.”

– Thaddeus Surber “Minnesota Moose—Then and Now” (PDF)

Eighteen years later, Surber noted that moose hunting had ended in 1922, and said he doubted the population had still returned to its former glory.

“It is preeminently a beast of the wild, a great wanderer even in primitive wilderness. Increased activity and invasion of its retreat by crews of men building roads, with attendant blasting; forest fires which usually follow logging operations, and which destroy its natural browse for one or more seasons, and the presence of many men wandering through their range has all had an increasing tendency to drive them into more congenial environment across the Canadian border, never to return.”

Canoe country comes into its own

In 1949, the Volunteer published an essay by George L. Peterson. He shared tales from a canoe trip starting at Lake One, east of Ely, to Insula Lake. It’s still a popular route.

“We loafed at the portages, boiled tea to go with our cold lunch and luxuriated in the natural loveliness of our surroundings. The only discordant note was an airplane rushing by. All sensed that such fast craft could mean the end of the canoe wilderness, for canoeing does not continue for long where either roads or air trails become established. Back at our campfire, we talked far into the night about the long battle to preserve the wilderness area. Sig Olson of Ely was along, a veteran of that struggle to keep the zone free first from power dams, then indiscriminate timber cutting, then roads and resorts, and now airplanes.”

– George L. Peterson “More About Canoe Country” (PDF)

Also on the trip were the Superior National Forest Supervisor and local district ranger, as well as others. The party included Sigurd Olson, who had already made a name for himself as a wilderness writer and advocate, though his first book was still seven years away. The article continues to lay out the opposing sides of the effort to ban airplanes in what’s now the Boundary Waters. It was an early chapter of the battles over protecting the wilderness.

“Around the campfire, we asked one another why Minnesota and America couldn’t spare this one small corner for preservation from high speed travel—a retreat where future generations could come to enjoy the tranquil ministration of nature’s fine therapy. As the nation becomes more crowded the need for such a refuge will increase. Yet unless the exploitation by plane and resort is stopped now, tomorrow may be too late.”

– George L. Peterson

Protection policies

Fast-forward 15 years, the debate over permanent protection for canoe country continued. The Wilderness Act of 1964 was being debated in Congress when the Conservation Volunteer ran a point-counterpoint pair of essays about the value of wilderness protection.

The arguments have not changed much since these publications. It started in the winter of 1963 with an essay by Richard Martin, a forester with the Bureau of Land Management in Idaho. His essay “A Plea for Moderation” asserted that wilderness was only for the few.

“We must all keep in mind that only a small percentage of the total population is able to afford wilderness use in terms of the money or time involved. You who are experienced wilderness users realize that this type of recreation requires a long period of time to enter and travel a wilderness region. Many times special equipment, such as canoes, pack animals, tents, or pack sacks, is essential and too expensive for the casual recreationist.”

– Richard Martin “A Plea For Moderation” (PDF)

Morris Patterson, a wildlife manager and member of the Izaak Walton League—Minnesota’s wilderness committee, responded in the next issue:

“[D]o we need — really need —the small amount of natural resources within the wilderness areas? We already have more of nearly everything than we can use. About the only commodities in short supply are fresh air, clean water and space.”

– Morris Patterson “The Wilderness Question” (PDF)

Ultimately, Congress passed the Wilderness Act and it was signed into law. It included large exceptions to wilderness regulations for the Boundary Waters, including areas where motors and logging were still allowed. Those issues were not settled for another 14 years.

Pollution problems

Around the same time that wilderness advocates were celebrating the passage of that final legislation to manage use of the Boundary Waters, a problem that didn’t respect lines on a map emerged.

Acid rain became a growing concern in the 1970s and 1980s. The Volunteer covered the issue in 1978 with an article by Steve Payne. The United States had just passed the Clean Air Act, protecting air quality in the Boundary Waters and Voyageurs National Park, and limiting emissions from power plants that can cause rain to acidify long distances away. But then, a power plant proposed in Canada, 40 miles from the Boundary Waters in Atikokan, Ontario, became a worry. Steve Payne, part of The Wilderness Society, alerted the Volunteer‘s readers.

“Environmentalists have warned that pollution from the plant would exceed provisions protecting our national parks and wilderness units under the Clean Air Act amendments. During public hearings conducted last summer by the U. S. State Department, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency stated that ‘the siting of this facility in close proximity to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area will probably result in some degradation of the air quality in the BWCA regardless of what pollution control equipment is installed.’ The MPCA’s prediction: Pollutants from the plant may reduce visibility in the wilderness and rain acid on its soil and softwater lakes.”

– Steve Payne “Acid Rain In” (PDF)

National Park needs

Shortly after the Boundary Waters was first designated as wilderness, an effort to protect the big border lakes to its west as a National Park gained steam.

While Congress was debating the legislation, the Volunteer dedicated an issue to celebrating the region that includes Rainy, Kabetogama, Namakan, Sand Point and other lakes. It included an essay by author and advocate Sigurd Olson, who the magazine called a “living Minnesota legend.”

“When we talk about the intangible values of the Voyageurs area we know such values are a composite of all the cultural facets of the region, that Voyageurs National Park is more than terrain. It is in a sense a living storehouse of beauty, of historical and scientific significance. If museums are places where the treasures of a people are safeguarded and cherished then Voyageurs is truly such a place.

“The National Park Service will interpret these values to visitors, using all the knowledge and expertise of half a century of experience in making them live. It will do this through interpretive centers, nature trails, and illustrated materials, using modern techniques to explain them to the public. People want to learn about such an area as Voyageurs, especially the young, and the Service knows that knowledge breeds appreciation and a sense of stewardship which hopefully will guard the region from unwise use and preserve its rare and often fragile qualities.”

– Sigurd Olson “The Values of Voyageurs National Park” (PDF)

Olson wrote the essay while Congress was still debating Voyageurs National Park, and had passed the authorizing legislation by the time the article was published. The park itself was established in 1975.

Wilderness for all

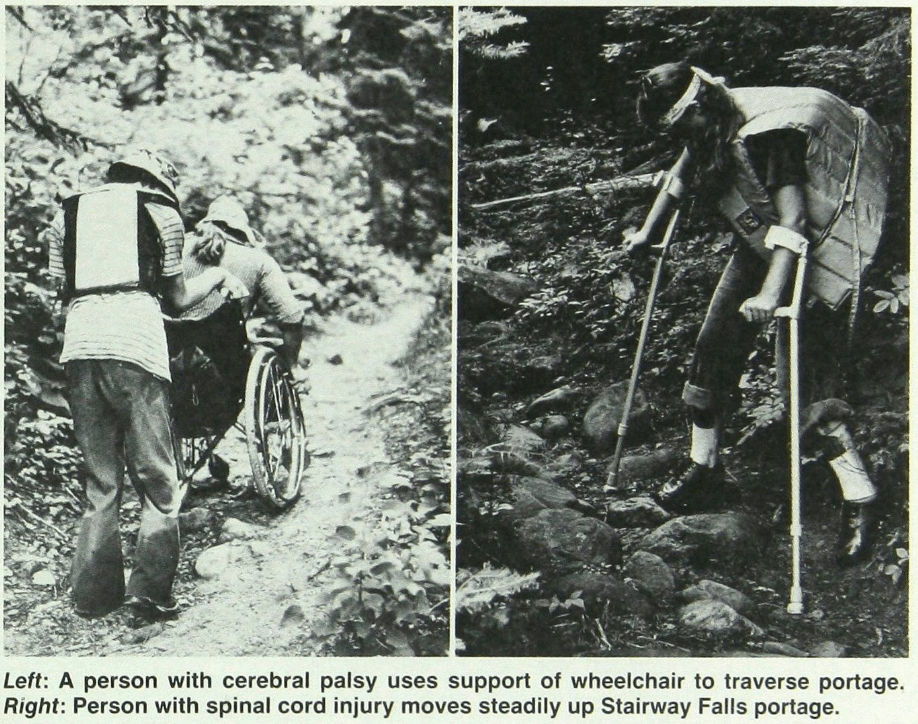

Traveling in canoe country is known for its rugged challenges. That might have meant that it was only accessible to the able-bodied, but one organization was determined to let people with mobility impairments experience it, too.

In 1986, the Volunteer published an article by Greg Lais, founder of Wilderness Inquiry, which offered Boundary Waters trips for paralyzed people and others who have unique challenges.

Wheelchairs, dog sleds, and canoes have little in common, but they sometimes come together in the wilds of northeastern Minnesota. Since 1978, a non-profit Minnesota group called Wilderness Inquiry II has conducted extended wilderness canoe and dog-sled trips with physically disabled persons who are seeking to experience the rigors and solitude of wilderness camping.

Youngsters and adults, ages 7 to 82 — some having such disabilities as quadriplegia, paraplegia, spina-bifida, cerebral palsy, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, blindness, and deafness — join together in this unusual opportunity. By working together and experimenting with new ideas, participants team up to overcome the challenges of wilderness travel.

– Greg Lais “Can Do! Wilderness Travel with Physically Disabled Persons” (PDF)

Wilderness Inquiry is still in operation today, providing powerful wilderness experiences to anyone who is interested, based on decades of experience and experimenting with new ideas.

Dark skies

The joys of wilderness never seem to wear out. In the 1990s, writer Laurie Allmann published an excerpt about the wonders of the northwoods in the depths of winter. Considering the Boundary Waters (and Voyageurs National Park) recently received designation by the International Dark Skies Association, Allmann’s observations about its value ring more true today than ever.

“On satellite photographs of North America taken at night, in which all the city lights shine like constellations, this is one of the blessed black spaces. Sprawled in the darkness before me are millions of acres of wild country, from the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness on into Canada’s Quetico Provincial Park.”

– Laurie Allmann “Boundary Waters Wilderness: January” (PDF)

Silent and still

While wilderness management and protection are still important topics, the Volunteer has also established a long history of simply celebrating the wonders of the wilds. Paul Gruchow was another wilderness writer who wrote about the Boundary Waters in several books, and in the Volunteer. An essay titled “Grace of the Wild” published in 1998 was an excerpt of his book bearing the same name that was published the previous year. Gruchow lyrically recounts the unique human experience of feeling small in a wild land.

“At the narrows of the lake, I cross over a little arch of land and put in at the river, which, in this shadowy morning light, looks like a dark artery, or vein, running deep in the dense body of a forest so tropically profuse that it seems impervious, foreign, organismic, a place where the trees cannot be seen for the forest. I stifle my breath, so raucous it seems in the surrounding stillness, and paddle my way dreamily upriver, turning the blade at the end of each stroke and pulling it forward underwater so as not to violate the reverential air.”

– Paul Gruchow “The Grace of Wild” (PDF)

Still publishing wild words

The Volunteer continues to report on the many facets of the Boundary Waters and surrounding region. That includes essays about adventures in canoe country, as well as sharing recent scientific research.

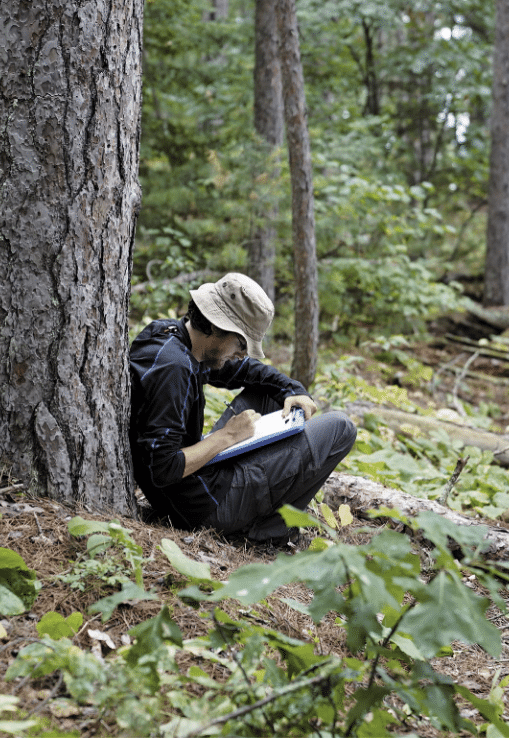

In 2017, the magazine was one of the first to publish an article about the study of tree rings in the wilderness that have helped reconstruct the history of humans and fire. Written by researcher Evan Larson, the article explains how scientists can find clues to how people have shaped the region’s forests for centuries.

The trees at this site had stories to tell. Nearby, the trunk of a fire-scarred, wind-thrown red pine displayed a long, vertical wound. Upon closer inspection, marks from an ax were evident, but barely, as centuries of healing wood curled over the wound. The injury was intentional. At one time, this injury ran thick with resin. When combined with wood ash and animal fat, this resin created the gum used to seal the seams of birch-bark canoes. Scanning the forest, we noted that nearly every large red pine within sight bore a similar scar.

By examining annual growth rings in core samples taken from tree trunks, we found that many pines at this site were more than 250 years old. Distinct injuries recorded within their rings denoted the passage of multiple low-severity surface fires that damaged but did not kill many of these trees. In all, 16 fires burned here between 1660 and 1909, after which fires abruptly ceased.

– Evan Larson “What is Wilderness” (PDF)

Wild winter

One of the most recent Boundary Waters stories in the Volunteer features a group of friends enjoying winter in the wilderness. Blane Klemek explains how winter travel in the Boundary Waters is more challenging, but also exhilarating.

“Before long, we started off, listening to the steady swishing of skis or clomping of snowshoes and our own labored breaths. We stopped at each portage to rest and offer each other encouraging words and help. The portages were exhausting — twice as hard to negotiate in the winter as they were in the summer. But all that labor was worth it for the chance to feel the sun’s warmth on our faces while taking in the panoramic beauty around us. We saw breathtaking vistas on rocky outcrops overlooking the Sawtooth Mountains. We admired tranquil, snow-covered lakes ringed with weather-beaten white pines and twisted northern white cedars. Overhead, a brilliant blue, cloudless sky contrasted sharply with the sprawling and blinding blankets of snow.

– Blane Klemek “When Heaven Freezes Over” (PDF)