The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) has affirmed a permit issued to PolyMet three years ago, and which was contested by Ojibwe tribes and environmental groups. The issue is whether PolyMet plans to expand its mine in the future, pushing it to a size that would require greater protections for air quality. At its current proposed size, it is subject to less stringent standards. Opponents argue PolyMet is engaged in what the Environmental Protection Agency calls “sham permitting.”

The concern is that the strategy is essentially bait-and-switch, and is not allowed by federal authorities. The groups say PolyMet announced its plans for a larger mine to Canadian regulators after a comment period closed when the information could have been considered by Minnesota agencies.

The Minnesota Court of Appeals in July ordered the MPCA to review the permit again, in the light of information about a potential expansion. The process focused on a technical report PolyMet submitted to Canadian authorities in March 2018 that indicated PolyMet is considering a mine two to four times as large as indicated in its current proposal.

On Monday, the MPCA said it had concluded the review and found no reason to change the permit.

“Based on its review of the Technical Report, MPCA determined that the expansion scenarios are ‘speculative at best,’ and referred to statements in the Technical Report providing that ‘There is no certainty that the results for these two cases will be realized,'” the agency wrote.

The EPA defines “sham permitting” as “permits with conditions that do not reflect a source’s planned mode of operation.” Air quality regulations call for different actions to be taken by air emissions sources depending on the scale of their operation. By receiving a permit as a “minor” source of emissions, PolyMet can more easily and economically open its mine. Environmentalists fear the company will follow permitting by an expansion proposal which will be harder to reject — or include stringent air quality protections.

The Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy (MCEA) argues that the financial information laid out in the report shows that the mine is not viable at its current smaller size. The state regulators say the project could become “more economical” at its current size if “some projections” for rising copper demand and prices come true.

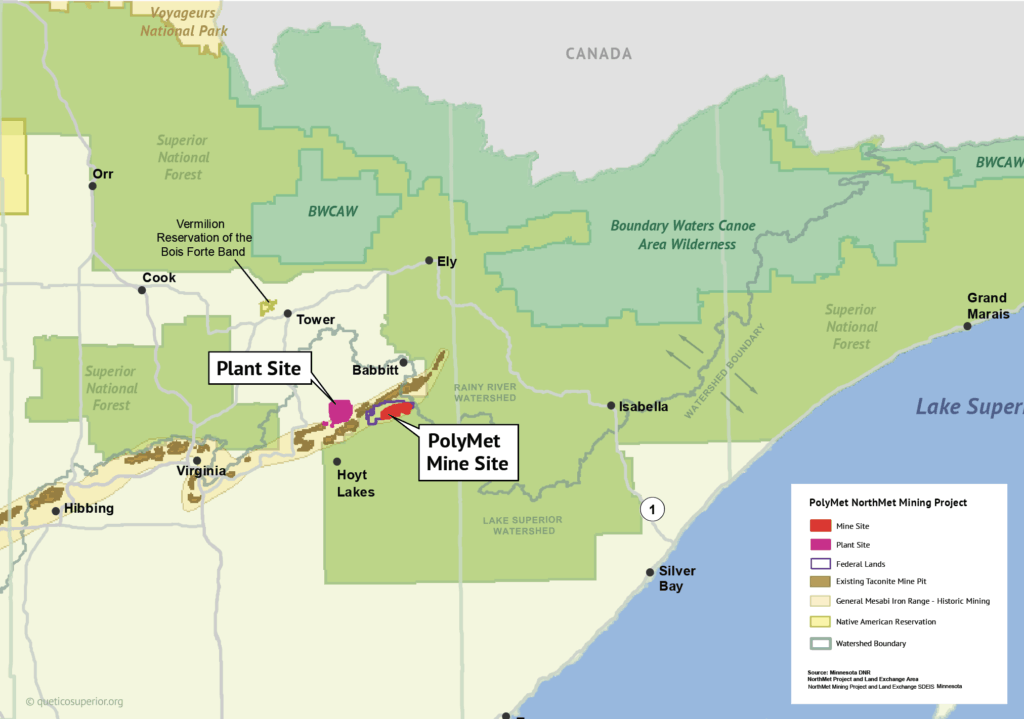

PolyMet says the decision is a “big step” toward opening the copper-nickel mine, the first that would operate in the state of Minnesota.

“As we have steadfastly maintained, the facts and science prove the project will meet air quality standards. That has never been in doubt,” said Jon Cherry, chairman, president and CEO.

MCEA responded to the decision on Monday by saying it is reviewing it and considering an appeal.

“We are disappointed that the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency has once again failed to conduct a rigorous investigation into the facts surrounding the size and scale of PolyMet’s true mining plans as shared with investors and securities regulators,” said JT Haines, MCEA’s Northeastern Minnesota program director. “Our state agencies need to probe these issues, not side-step them.”

PolyMet is still not allowed to begin construction or operation of the proposed mine. Its key “permit to mine” from the DNR, a water quality permit from the MPCA, and a wetlands permit from the Army Corps of Engineers are all still tied up in legal battles.

More information:

- State environmental regulators stand by PolyMet air permit – MPR News

- Air Emissions Permit – Supplemental Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law and Order – MPCA (PDF)

- Protecting Minnesota from PolyMet’s dangerous mine and dam