July 21st…the fire burns across an island on Shoepack Lake. Photo courtesy Voyageurs National Park

Federal parks and forest officials had a perfect opportunity last summer to advance two of their goals for Voyageurs National Park: restoring fire as part of the natural ecosystem and regenerating white pine forests. The last large fire in the area had occurred in 1936 and the park was established in 1971.

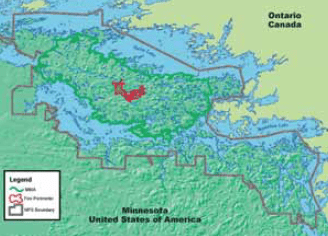

On July 8, an Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources detection aircraft discovered a fire burning between Loiten and Shoepack lakes on the Kabetogama Peninsula. An alert went out to the Voyageurs Park. Using their “Decision Criteria for Wildland Fire Use” park staff made the decision to let the fire to burn naturally. The eligibility criteria for making the go-ahead decision included: immediate and potential threats to life, property and resources; acceptable fire effects on natural and cultural resources; current and forecasted fire danger and expected fire behavior; and availability of fire management

team resources.

The fire burned for the next two and a half months and became know as the Section 33 Fire. The fire naturally consumed 1,435 of the park’s 170,000 acres of land, or less than 1%, before gradually dying out in late August. If 2004 had been a typical summer, the wildfire that was sparked by a lightning strike during a July 5 thunderstorm would have been put out immediately with water, said Barbara West, the park’s superintendent. But the weather was cool and wet and the fire started in the center of the Kabetogama Peninsula, where it wouldn’t threaten life or property no matter which direction it moved.

The day-by-day progress of the fire is described by Dave Soleim, the park’s Fire Management Officer, in the 2004 annual report of federal and state fire agencies in Minnesota, the Minnesota Incident Command System (MINICS):

“Two days after the fire was detected, a south wind event pushed the fire along a pine covered ridge to 55 acres before two to three inches of rain was received that night. The fire was monitored daily with only limited smoke visibility until July 21 when the fire crossed a drainage. Driven by strong west winds the fire pushed towards Shoepack Lake, spotting across the lake. Over the next couple days the fire continued to spread and again spotted to the north shore of Shoepack Lake where it became well established on the north side of the lake. Weather and fire behavior forecasts indicated that the fire had potential to move to the shore of Rainy Lake within one to two burning periods. Twenty private and use and occupancy cabins dotted the islands in the projected fire growth path. Protection measures were employed to protect these structures, with all cabins and outbuildings having sprinkler systems deployed. On July 27…the forecasted wind event…came with cloud cover and high humidity and fire growth was minimal. After August 5th, rain and high humidity, little wind and cold quelled the fire, and it grew very little. Over the next several weeks isolated hotspots were observed but there was little growth. The 1,435-acre Section 33 Fire still burned less than 1% of the park’s 170,000 acres of land.”

West showed spectacular photos and described the planning and progress of the 2004 blaze at the Voyageurs National Park Association board of directors meeting in Minneapolis on Nov. 30.

One dramatic image in her presentation showed sections of an island in Shoepack Lake that were burned on July 21, when strong westerly winds drove what had been a smoldering fire around and over the lake, incinerating trees that contained an eagle nest. The fire grew from 60 to 176 acres that day and “ran over the island as if there was no water in between,” West said. The adult eagles were spotted soon afterward in another tree on the island, but it was feared the eaglet had died until it was spotted days later, she said.

West described how the fire would “munch” slowly along for days through the fir-balsam understory and birch-aspen overstory, until strong winds would come. “Then the fire would start running like an inferno, with short crown fire runs, and then it would start to rain and slow it down again,” she said.

Each day, West had to run through a checklist of factors and conditions, and she was responsible for the daily decision to let the burning continue. “By the time it was over, I had a great deal of admiration for the guys who make this their lives,” West said.

Officials shut down campsites, houseboat sites and trails, she recalled, and as time went on the houseboat companies “got testy.” Concerns included whether the fire would reach cabins, Kempton Channels or Rainy Lake, but none of these happened. The fire stayed within the maximum manageable area defined by the fire management plan.

At one point, 58 people were working to manage the fire and prepare for contingencies, including local crews and equipment from the Interagency Fire Center in Grand Rapids and crews from Montana, Arizona and New Mexico. These included the Southwest Fire Use Management Team. The national teams specialize in managing Wildland Fire Use events. The total cost of monitoring and managing the fire was approximately $450,000, West said.

By the end of August, new ferns and other plants were already sprouting in areas that had been burned. The fire burned so hot that it’s difficult to know whether white pines will regenerate naturally, West said. Monitoring plots will be studied in the spring, and she said it may be a challenge to keep deer away from new pine seedlings.

West noted that a major natural event happens in the area approximately once every 100 years, causing the ecosystem to be renewed.

“The management of wildland fire for resource benefits is among the highest risk and highest consequence programs administered by federal wildland fire management agencies,” Soleim wrote in the MINICS report. “Wildland fire is as fundamental to Park ecosystems as rain, snow and wind…(the) Section 33 Fire brought back a much-missed element of the natural community.”

by Diane Rose, Wilderness News Contributor