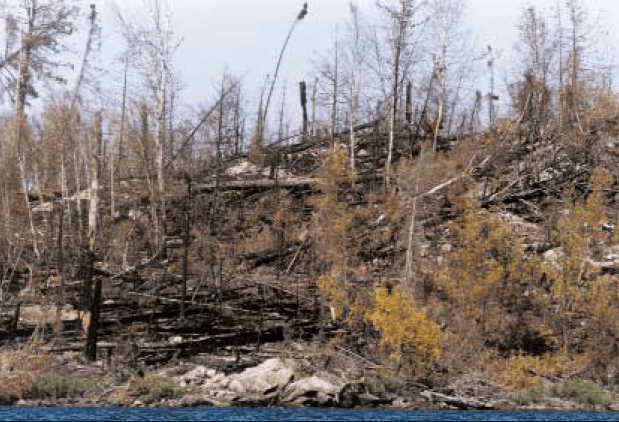

Results of the prescribed burn that took place on Three Mile Island last September.

With the completion last September of the Magnetic Lake and Three Mile Island prescribed burns, the Forest Service has now completed 3,700 acres of the planned 75,000 acres within the BWCA. As a follow up to our story “Fall Burning Increases in the BWCA, Remains Short of Goal” (Winter 2003) Wilderness News asked the Forest Service to respond to a list of questions pertaining to the Three Mile Island prescribed burn on Seagull Lake. Patricia Johnson, the East Zone Fuels Planner for the Superior National Forest, and Dennis Neitzke, the District Ranger, responded to our questions. Their answers may help us understand the business of prescribed burning, and the regeneration process that follows each BWCA burn.

Did the fire go as planned, burning only the blown down trees, and not the standing trees?

The fire did go as planned as far as burning the blowdown areas. In wet drainages and in the standing timber, the fire did not spread much and there is still a standing live component of tamarack, spruce, cedar and hardwoods in those areas. There was some mortality

(30-50%) of the standing live timber. There is now a mosaic of patches that burned and patches that did not burn. When looking at the island both on the ground and from the air, the fire looks as close to a natural fire as we could have hoped for. That is our goal for the Boundary Waters burns that we are conducting.

Were the standing old growth cedar and red pine trees saved?

In the old growth cedar areas of the island, there was between 15 and 35% mortality. From postburn evaluations there last fall, 14% perished, 68% survived, and 18% were undeterminable at that time. The very old cedar and pine of concern appear to have not been affected as of yet. Sometimes the effects of burns in terms of mortality may not show for a couple years, but as of now, it looks very good.

Were the standing trees along the shoreline saved?

About 50% of the shoreline was burned, and as already mentioned, there was between 30-50% mortality in the standing live timber. The areas where the most mortality can be found are where the blowdown was heavy nearby and the heat from the fire was very intense, thus causing mortality.

We were told that the prescribed burn spotted to an adjoining island which also burned. Is this true? And if so, was this island part of the prescribed burn plan?

(Spotting refers to embers from the main fire landing outside the fire perimeter causing a fire to ignite.)

Yes, the fire spotted to three small islands nearby. About 80% of a 1 acre island burned and the fires on the other two islands were

extinguished by fire crews. Originally, the Environmental Impact Study (EIS), included these islands in the Three Mile Island prescribed burn plan because of the high fuel loads and their proximity to Fish Hook island and the island occupied by the Wilderness Canoe Base (both islands were excluded in the EIS plan). The EIS study calculated that if a wildfire were to occur on one of these islands it would be nearly impossible to stop fire from jumping to the larger islands. However, due to public opposition these three islands were removed from the burn plan. As a result, when the fire spotted from Three Mile Island, we had to extinguished the fires. Incidentally, just this spring we had another fire on one of these islands and the entire island burned.

What follow-up information does the Forest Service have about the condition of the soil after the burn?

Soil survey monitoring of conditions after a burn is part of every prescribed burn plan for the BWCA. There were a variety of effects to

the soils on Three Mile Island because the prescribed fire was a mosaic pattern. Where there were heavy fuel loads down on rock outcroppings the fire burned intensely, resulting in areas where the duff was completely consumed.

In other areas where the fire was less intense, the duff remains intact. Duff is the partly decayed organic matter on the forest floor. Post-burn surveys show about 50% of the duff was consumed. The soil itself was not affected much. As of yet, no soil sterilization

has been identified by monitors and soil scientists at the site. With 50% of the duff layer still present, the soil will be well protected from erosion and other negative effects. From a regeneration perspective, the duff layer needs to be reduced somewhat for seedlings to be

able to regenerate, especially pine species. The reduction that was seen on Three Mile will provide a good seed bed for tree species to seed in. Once again, I want to emphasize that the effects on the soil were very similar to what one would see in a wildfire, there were

no unusual effects.

Some speculate that the use of liquid fire accelerants create fires which can burn too hot resulting in soil sterilization. What can you tell us about this? Does the use of liquid fire propellant increase the risk of soil sterilization?

The soil was not sterilized on Three Mile Island. One indication of this is the amount of herbaceous material that is coming up this year. If the soil had been sterilized, there would be no vegetation sprouting up.

In fact, we did not use a liquid fire propellant on Three Mile. Instead, we choose to use a “plastic sphere dispenser” (PSD) which dispenses little plastic balls containing a chemical that when injected with another chemical causes fire ignition. We use the PSD on burns that are prescribed for lower intensity fire as was the case for the Three Mile Island. We knew we did not want to risk burning the standing live trees with an intense fire.

You may recall that we used the helitorch on the Magnetic Lake prescribed burn. The helitorch dispenses a liquid fire propellant and because you can add more fire quickly to a larger area the result is often a hotter fire. However, the severity of a burn has to do more with the specific conditions of each burn rather than which ignition method is used. Factors to consider include: the weather conditions, humidity in the air, moisture content of the fuels (blowdown), the fuel loads (volume of blowdown and debris on the ground), and how fast the area is ignited. The risk of an intense fire increases with dry weather conditions and heavy fuel loads.

Would a sterilized soil result in soil erosion before the regeneration takes place?

Soil sterilization does not always correlate to soil erosion. What plays a larger part in soil erosion is the steepness of a slope that the soil sits on and the amount of duff left on the site. Three Mile Island as a whole does not have a lot of steep slopes. Also, as mentioned before, with 50% of the duff still intact the soil should be protected from erosion and washouts.

Is there evidence of new growth this spring?

A group of researchers and Forest Service personnel looked at the burn in mid-May. Already there was quite a bit of vegetation coming up. The fire released a lot of nutrients back into the soil, which results in quite a bit of new vegetation out there. Most of the vegetation is herbaceous this year.

What can we expect the regeneration cycle to look like?

This first year I would expect to see some herbs and brush regenerating and maybe seedlings. If aspen and birch regenerate this first year they could reach up to 2′ tall, whereas jack pine and red pine may only reach 2-3″ in the first year. In the second year, we should start to see more seedlings and the brush will grow 2-4′ in height. The jack pine seedling from the year before may reach 8″ in height, and the aspen 3′ in height. The red pine seedlings will be less than 6″. By the fifth year, the aspen will be 4-6′ tall, the jack pine and red pine around 1′, and the grass, herbs and woody shrubs will disappear in the shade of the young seedling trees.

Will the indigenous tree species reappear or will they be replaced with aspen and birch?

How many seedlings and of what kind is hard to determine just yet. We are hoping that near the pine stands (along the shorelines) where there was good survival, that we will see the red pines returning. There is a very good chance for this considering the seed source left in the living pine that burned. Where there was jack pine and spruce (in the upland areas and on ridges), we are hoping these species will grow back. Birch started to come in on the island over the last 30 years, so there will probably be some component of birch as well. There was also a small component of aspen present on the islands so we will probably see some of that too. How many of which species is still hard to tell. Much of it depends on environmental conditions (i.e. weather) and how much of a seed crop develops in the remaining standing timber.

Is there a plan to replant the island with native red and white pines and cedar if the island does not reseed itself? Or do we let nature take its course?

The plan is for natural regeneration on the island. According to the Wilderness Act of 1964, the Forest Service is not allowed to manipulate the vegetation of the wilderness with artificial processes and replanting is considered an artificial process.

What happened to the animal inhabitants of the island before and after the fire?

There are a variety of immediate effects and long term effects on the wildlife, some positive, some negative. Remember that the wildlife found in the forest types of Northern Minnesota have adapted with fire over time and have developed traits that help them survive during fire. During the burning process, some larger animals were flushed out and proceeded to swim or fly to adjacent islands. When we burned the island we actually flushed out a few moose that swam to adjacent islands. Many animal inhabitants probably found refuge in the unburned areas. Some animals (i.e. the smaller ground dwelling animals) went underground for safety. The fire was slow enough in its spread rate that most animals were able to move around and find refuge as the fire burned. Because prescribed burning moves at slower rates than a natural wildfire would, animals have a better chance to survive. But, unfortunately, some animals probably did perish.

Long term, fire has some very positive effects for wildlife. Because fire provides a flush of nutrients to the soil, there is an abundance of herbaceous material that grows afterwards. Many browsing animals, such as moose, benefit from the increase browsing food source available. Many bugs that pollinate those plants such as bees and butterflies, can also be prolific after fire. Berries can be more abundant after fire and for upwards of 3-10 years will provide a great food source for bears and rodents.

With an increase in the rodent population on the island we will see an increase in Red Tailed Hawks and Northern Hawk Owls in the area. Fires also provide a host of burned dead material which attracts all kinds of bugs that feed off the decomposed and charred material. Black-Backed Woodpeckers prosper from fires and were observed this past May on the island.

What was learned (pro or con) from this fire that the Forest Service can apply to future prescribed burns?

One very good thing we learned from this burn that will help us in the future is that we can burn under more humid conditions than we anticipated. We burned Three Mile Island on a day that was overcast, towards the end of the day, and we had a very light rain shower. The blowdown burned despite these conditions. We also learned that the PSD machine can be a very effective method and will help minimize fire effects by creating less intense fires. And, from a logistics standpoint, the PSD is much easier to operate and much less hazardous compared to the helitorch, which involves hauling a lot of fuel mixtures into the wilderness. We also learned that we can mimic natural fires with prescribed burning, creating mosaic burn patterns. This means our effects would not be outside of what would naturally occur.

In conclusion, what would you like to tell our Wilderness News audience?

Fire has immediate effects that occur while burning (what we call primary) and effects that

occur some time after the burn (secondary). Sometimes the primary and secondary effects are not always positive, but overall there are some very positive effects of fire. Fire is a natural part of our ecosystem and many plants and animals have adapted to that over time. All these effects, whether negative or positive, are part of the natural cycle of the forest.

This article was published in Wilderness News Summer 2003