By Greg Seitz

The soul of Sigurd and Elizabeth Olson lives on at their home in Ely. The soul smells of fresh-baked cookies in the kitchen. In the writing shack on the property, it smells of cedar. It sounds like a breeze rustling the tall red pines Sig planted as seedlings, of croaking ravens and scuttling red squirrels. It lives on, just as Sigurd’s work to preserve wilderness continues. Now that the Listening Point Foundation has purchased the property, containing both the house and the writing shack, the work will continue there as it has since the Olsons bought it in 1934.

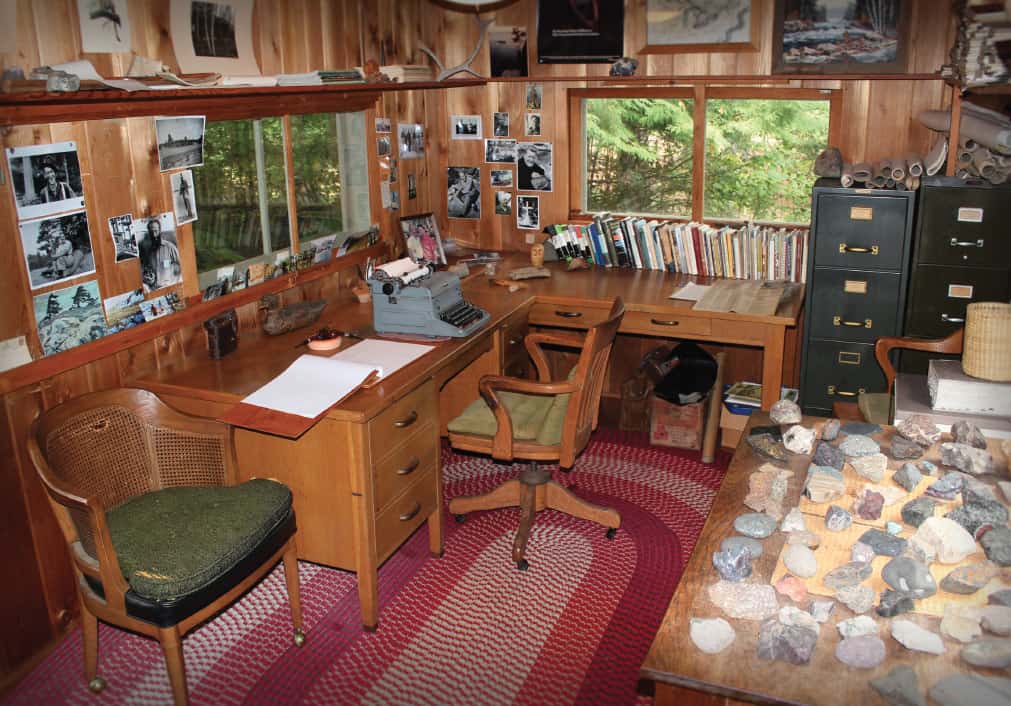

Situated on a quiet street atop a ridge on the south side of town, the property is where, for 48 years, the owners raised their family while orchestrating campaigns to permanently protect the Boundary Waters and other wilderness around the United States. It is also where Sigurd wrote all of his books, sequestered in the old garage that he repurposed as an office.

Elizabeth remained in the house until her death in 1994, twelve years after Sigurd passed away while snowshoeing on the property in 1982. Longtime family friends Chuck and Marty Wick then bought the home, and made it their own while preserving the sense of the Olsons and the history that had happened there. Twenty years later, the Wicks sold it to the Foundation to continue the stewardship.

As executive director, Alanna Dore felt it was essential that the Listening Point Foundation acquire this historic property. For her first 10 years as director, she ran the group from her dining room. Most of the work was focused on the cabin at Listening Point on Burntside Lake. But, modern times called for a place the group could call home as it seeks to expand its efforts to reach a new generation of readers and wilderness advocates.

“We don’t know all the opportunities it’s going to present,” said Dore.

It was this house that countless collaborators came to eat cookies, drink tea, and discuss the idea that some places on earth ought to be left alone. The room that the Olsons added to the house to accommodate just such conversations has not changed since they lived there. “The Porch” has windows on three sides, a big pine table in the middle, a stuffed owl, fish-themed lamps, a few books on the shelves, and a view of the red pines which now tower above, and a stone wall he built around the edge of the yard.

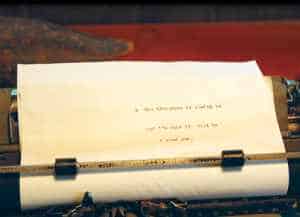

The other place unchanged is the writing shack (where this article was written). The sheet of paper with Sigurd’s famous last written words remains in the Royal typewriter, the keys he pressed to type: “A New Adventure is coming up and I’m sure it will be a good one,” before going out the door for his last snowshoe walk. Dozens of rocks and other natural items are displayed on a desk, perhaps totems to reconnect him with the wilderness he so evocatively wrote about and the stories that he told.

To sit in the shack and write was an honor—and intimidating. Sigurd’s pipe smoke must have swirled around this room as he put on paper ideas and images that no one else so magically captured of the power and beauty of canoe country. The garage was “the birthplace of a new language,” as Julie Paleen Aronow wrote in the summer 2015 “View From Listening Point” newsletter. “The language of wilderness was created there from the passion and experiences of the old voyageur.”

At first the words came easily to me, my writer’s block lifted by Sigurd’s gentle spirit and in the morning a thousand words blurred by. But after a lunch trip to Listening Point, when I returned for the afternoon and evening, I found a feeling of inadequacy. Sigurd wrote books in the room that were beloved by millions, he sparked a movement that continues to bring a quarter million people to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness every year, he led nascent organizations that successfully preserved wild places, and he planned canoe trips along remote routes in northern Minnesota and far north into Canada.

I suddenly felt like an imposter.

My salvation was unimpressive at first. The wall that ringed the yard was overgrown with Virginia creeper, obscuring the stone behind floppy leaves. I had admired the wall as a relic of an important person’s hands, but it looked more like a ridge of stone. While I liked that it was there, it didn’t seem to serve any purpose. Its purpose seemed to be obscured by the weeds.

As the afternoon wound down, and as I struggled to regain the flow that I had felt that morning, Dore said goodbye. As she left, she suggested I could pull some weeds if I wanted. They had an open house coming up in a couple weeks and she thought if I wanted to work on something Sig had worked on, I could “do ten feet” or whatever.

I wanted to write, but I needed to weed that wall. The weeds came up easily, and soon exposed the wall’s purpose—and beauty. Etched with piles of red pine needles, it looked like the Canadian shield: the outcome of billion-year-old rock and two-mile-thick glaciers. A pile of glaciated rock, the duff of a few millennia nestled in the nooks.

Once I had weeded the section visible from the porch, I felt like I had earned the opportunity and I returned to the shack. The words came quickly.

This experience could be available to others in the future. Dore hopes to launch a writers-in-residence program, providing the opportunity to sleep in Sig’s bedroom and write in his shack. Dore envisions possibly leading some writing workshops as a trade for time.

The foundation hopes to use this new home base to help get Sigurd’s writing in the hands of more young people, who need nature and wilderness more than ever.

“Next year, education and young people are going to be our focus. The year of the young,” Dore says.

These new opportunities the property makes possible are exactly why it was important for the Foundation to acquire it.

When the Wicks told Dore last year that it was time for them to sell the property, she leapt into action. With a goal of raising $220,000 to buy the property, she got on the phone. She wasn’t intimidated by the nearly quarter-million dollars she had to raise, because the case for donations was pretty clear. This would ensure the property stayed in the hands of those who love what the Olsons stood for. In a matter of nine months, she had secured the funding from a couple dozen donors, and the Foundation and the Wicks closed the sale in December 2014.

Since then, Alanna Dore has led the charge to adapt the home into an office, museum, and community space. And she continues to bake cookies for visitors, using Elizabeth’s recipe.

Read more in Wilderness News Summer 2015