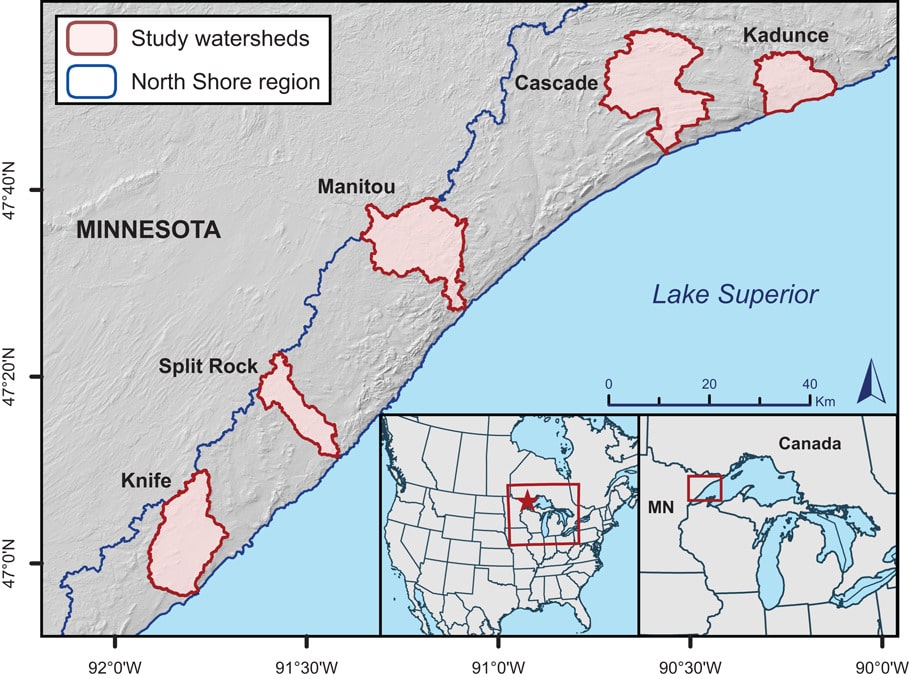

Scientists with the University of Minnesota have analyzed aerial photos stretching back to 1948 in an effort to understand the impact of beavers in five watersheds along Minnesota’s North Shore. The 70 years of data they extracted spanned the return to abundance of beavers to the region, after being nearly wiped out by hunting and habitat loss during white settlement.

The data has allowed them to study how much water is held back by beaver dams, a key benefit for protecting healthy streams. It shows that bringing back beavers has provided regional, steady benefits for the rivers — as well as the trout that call them home, and other parts of the ecosystem.

“Although there are many studies on how beavers change ecosystems, the scale of this study—spanning 70 years across five different watersheds—is really unprecedented and, as a result, gave us the unique opportunity to understand how beavers transform and engineer ecosystems over long time periods and large spatial scales,” said co-author Tom Gable. “We think this work will be of value to many conservationists, scientists and citizens who want to understand how reintroduced or recovering beaver populations can positively affect their ecosystems.”

Before European settlement, there were estimated to be 260 million beavers in the Upper Midwest region. But they were widely trapped between the 1600s and 1900s, and their numbers plummeted to near zero. Today, despite harvest restrictions and efforts to restore their population, there is still only about 10 percent of the original population. About 25,000 are still trapped each year in Minnesota.

Ultimately, bringing back beavers had immediate impacts on the landscape as the aquatic rodents dammed creeks and rivers, creating pond and wetland habitat and moderating flows to keep rivers flowing relatively steadily. But the study found the benefits increased with time and became consistent forces on the landscape and local hydrology.

Building resilience

Rather than being ephemeral impacts that only last as long as one beaver or beaver family, the benefits of the ponds and wetlands that beavers create last a long time.

“In combination with other recent research we conducted on beaver population dynamics in northern Minnesota, our study demonstrates the resilience and stability that beaver populations have within landscapes,” said Sean Johnson-Bice, lead author of the study. “Their populations at a landscape scale appear relatively unaffected by environmental conditions and, as such, they can be key drivers of freshwater habitat diversity and promoting ecosystem stability.”

The research was funded by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources for Minnesota’s Lake Superior Coastal Program as part of a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund, as recommended by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources.

Johnson-Bice conducted the work as a master’s student at the University of Minnesota-Duluth, and is currently pursuing his PhD in Manitoba. Other authors on the paper included Tom Gable, University of Minnesota researcher and lead of the Voyageur Wolf Project, and Steve Windels, Voyageurs National Park biologist. The fourth author was George Host, the now retired director of NRRI’s Forest and Land Initiative and Geographic Information System laboratory.

“Digitizing almost 800 historical and recent aerial photos from 1948 onward represents a tremendous effort on the part of Sean and the NRRI and Twin Cities GIS laboratories,” said Host. “The resulting dataset provided significant insights into the critical role beavers play in regulating water storage along the North Shore.”

But not everyone is a beaver believer. The Minnesota chapter of Trout Unlimited says forest changes along the North Shore after the logging era have resulted in “unnaturally high beaver densities” in the region. Logging removed largely coniferous forests, not preferred by beavers, which were replaced with much deciduous tree species that beavers prefer. Research supporting these claims has not been provided. The organization says beaver dams and ponds can raise water temperatures to levels that hurt trout. It calls for extensive beaver management (i.e. trapping) and restoring coniferous forests to the point it will naturally limit the population.

More information:

- Beavers support freshwater conservation and ecosystem stability – University of Minnesota

- Beavers – Voyageurs National Park

- Beaver (Castor canadensis) – Minnesota DNR

- Beaver management – Minnesota Trout Unlimited

Reference

Johnson-Bice, S.M., Gable, T.D., Windels, S.K. and Host, G.E. (2021), Relics of beavers past: time and population density drive scale-dependent patterns of ecosystem engineering. Ecography. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.05814