By Alissa Johnson

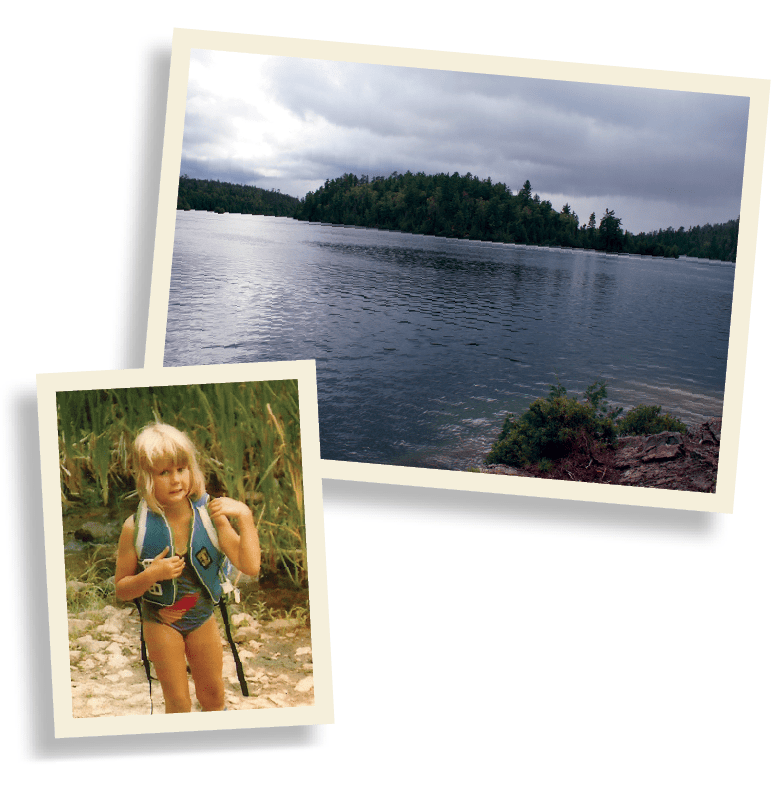

When I was a kid, paddling the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness with my family, I didn’t realize that the final word in its name had only been added in 1978—the same year I was born. Nor did I realize that the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act of 1978 was preceded by the Wilderness Act of 1964, which created a National Preservation System and a legal definition of wilderness:

“A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

I simply knew that in the Boundary Waters, we traveled by canoe, under the power of our own muscles. We slept in tents and cooked over fires, and we packed out what we carried in, including garbage. When we paddled away from campsites, I loved the way that I could look back and see no sign of our stay.

It’s not surprising, perhaps, that a young girl was ignorant of the law. A paddle dipping into a lake, fingers grazing its cool surface, seems very far away from the halls of Congress. But on the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, it seems important to understand its significance. The Act required eight years of debate and more than 60 drafts before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed it into law on September 3rd. It left some things in question. In the Boundary Waters, for example, motorboats and snowmobiles were allowed in areas where motorized use had been established, leaving room for great public debates. But the 1964 Act also laid the groundwork for the preservation of a region that I took for granted as a kid.

So I called Kris Reichenbach, Public Affairs Officer for the Superior National Forest. I wanted to talk to someone who has spent time explaining the Act to the public, had experience with an agency charged with enforcing the Act. I wanted to see whether our understanding of wilderness has changed as we face new factors like climate change and invasive species.

Reichenbach took me back to the beginning, the Act itself, reminding me that there is a reason people call the definition of wilderness poetic. “It’s an eloquent act. It’s not full of bureaucratic words as much as some other national legislation,” Reichenbach said. “It ties back to the passion. The people that were championing and writing the laws were touched [by wilderness] in such a way that they wrote this law differently.”

That didn’t mean, of course, that it was without interpretation. Land use managers had to determine what the use of words like untrammeled meant, and how to balance that with the impacts of visitors. They had to determine (and still do) the roles of recreational use, commercial use, and research. Agencies have to balance the preservation of wilderness character with a love from visitors so great there can be risk of loving a place to death.

In places like the Boundary Waters, Reichenbach told me, that means helping people understand what it means to prohibit mechanical devices or the principles of Leave No Trace. But it’s also about helping us understand that our very presence impacts the wilderness, in ways that are greater than packing out whatever we pack in.

There is, for example, the advance of cell phones and the idea that safety is a phone a call away. While emergencies will happen, a rescue itself can be intrusive, impacting that natural landscape and other visitors. If we’re careless or unprepared, our rescue can detract for other visitors’ wilderness experience. Or take the spread of nonnative and invasive species. Simply by entering the wilderness, we have the power to spread them further.

“There are very small areas scattered in wilderness where research has identified the highest risk [of nonnative and invasive species]. It’s usually areas where people are moving in. Visitors can make a big difference by cleaning equipment and making sure their boots are clean before moving into wilderness,” Reichenach told me.

This summer, the Forest Service will go so far as to engage the public in identifying infestations within the wilderness area. New identification books will help visitors identify nonnative and invasive species, and a postcard in the back of the book will make it easy for them to alert the Forest Service to their locations.

“We do monitoring,” Reichenbach said, “but in one million acres—three million in the whole Superior National Forest—we can’t see everything. Getting tips about infestations we didn’t know about may allow us to get in there early.”

Listening to Reichenbach, it occurred to me that the relationship between wilderness visitors and wilderness managers is changing. Protecting a wilderness area is no longer as simple as checking things at the door—mechanical devices, say, or motors. It’s about managing invasive species that can spread undetected, or understanding what climate change might mean for the region. We are all wilderness managers now, in ways that the legislators behind the 1964 Act never imagined.

When we enter wilderness, we can choose to see that reality or not. We can pack trash out or leave it behind. We can clean our boats for invasive species or move them into the wilderness without care. We can keep an eye out for invasive species or forget to send a postcard to the Forest Service. But when we choose to be responsible, to act in favor of wilderness, our actions themselves become the living definition of wilderness. We keep the vision behind the Wilderness Act alive. And in that way, it turns out that there is a direct connection between the legal definition of wilderness and dipping your paddle into the cool waters of a BWCAW lake—whether I knew it as a child or not.

From BWCA to BWCAW

When the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964, it left exceptions for established motorized use in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. Debates over the use of motorboats, snowmobiles and other land uses continued (and in some cases still do). The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act of 1978 sought to address many of those issues and officially named the area the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. Following are some of the key dates leading up to its passage, taken from www.queticosuperior.org:

1964 – Congress passes Wilderness Act after eight years of debate. BWCA is officially included in National Wilderness Preservation System. The Act prohibited the use of motorboats and snowmobiles within wilderness areas, with exceptions for areas where use was well established with the BWCA.

1965 – U.S. Secretary of Agriculture issues 13 directives dealing with BWCA, adding to no-cut zone, zoning for motorboats, establishing visitor registration and more.

1971 – Ontario announces moratorium on logging in Quetico Provincial Park.

1972 – President Nixon issues Executive Order prohibiting use of snowmobiles and recreational vehicles in all national wilderness areas.

1975 – 217,000 acre Voyageurs National Park established. Secretary of Agriculture imposes off-road vehicle ban in the BWCA.

1978 – On October 21st President Carter signs the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act into law. It ends logging, reduces motorboat lakes, phases out snowmobiling, restricts mining, and expands BWCA by 68,000 acres. Name officially becomes Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

Commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Wilderness Act with Wilderness News

Do you have a favorite photo from the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness? Share it with Wilderness News, and we’ll post it on our Facebook page. Email it to editor@queticosuperior.org or post it to www.facebook.com/WildernessNews. Be sure to include where it was taken and why the moment was meaningful. We’ll select a few to include in the fall print edition of Wilderness News.

Read more in the Spring 2014 issue of Wilderness News